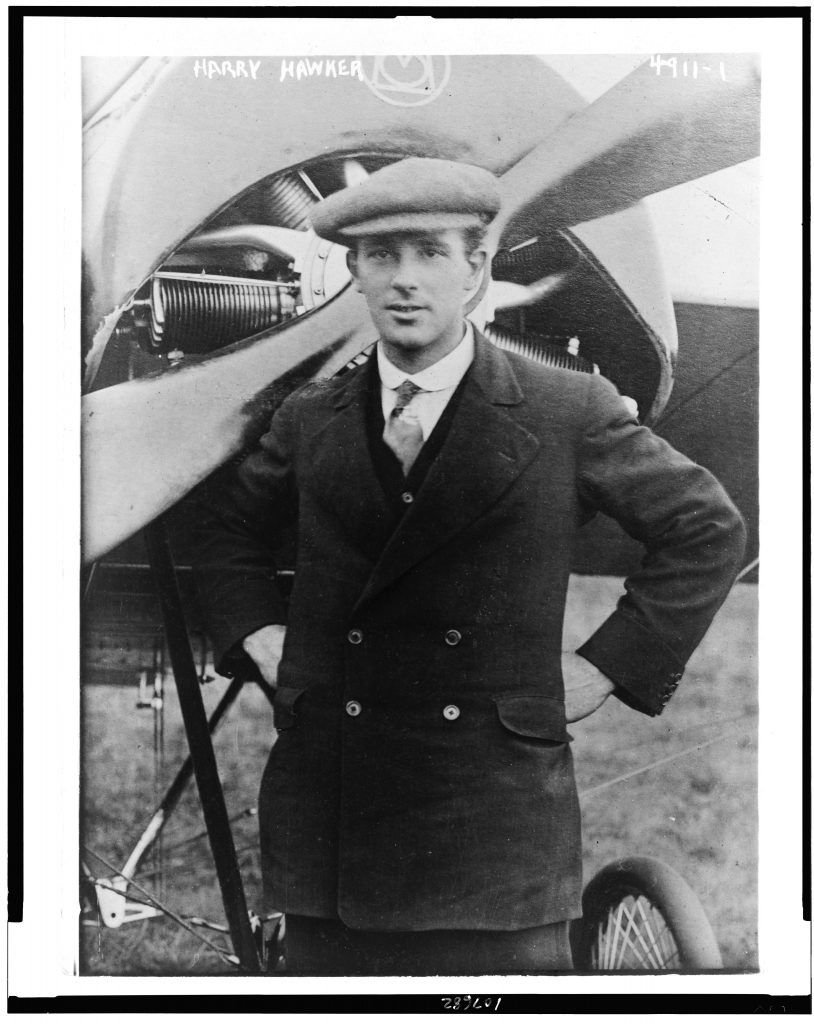

It’s exactly 100 years since an Australian aviation pioneer almost achieved the everlasting fame of a world first. Instead, he and his navigator responded coolly and calmly to an inflight emergency and lived to fly another day. The pilot’s name was Harry Hawker.

He was born in Moorabbin, Victoria, in 1889 where today the airport is named after him. He became a bicycle mechanic, then a motor vehicle mechanic, and having caught the aviation craze, travelled to Britain in 1911. There he learned to fly and was setting aviation records with all of 24 hours in his logbook. During the First World War he was a test pilot for British aircraft maker Sopwith, influencing many of its designs. In 1919, he piloted Sopwith’s entry to win the £10,000-pound prize offered by the Daily Mail newspaper for the first non-stop aeroplane crossing of the Atlantic Ocean.

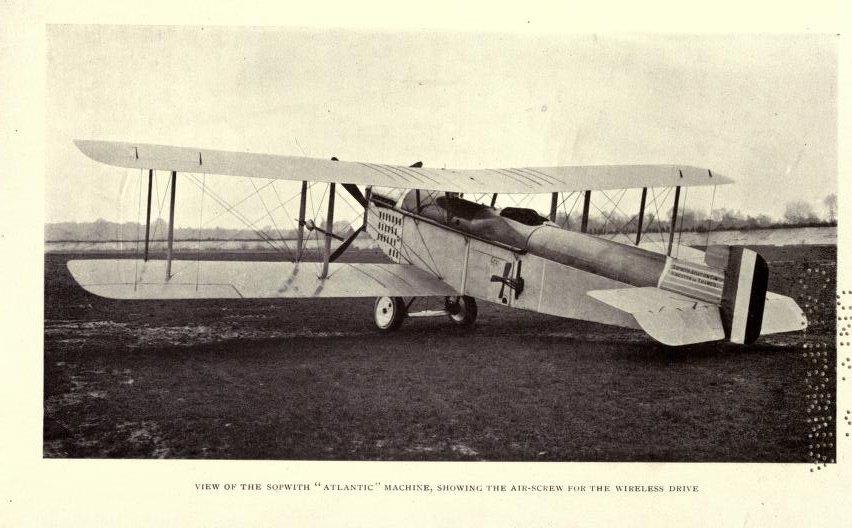

Hawker was about seven hours and 1200 km into his attempt to make the first aerial crossing of the Atlantic Ocean on 18 May 1919, when the radiator temperature in his custom-built Sopwith Atlantic single-engine biplane began to rise. Until then, the flight had gone well. ‘Getting off was just a little bit ticklish,’ Hawker wrote of their heavily loaded take-off, and instrument meteorological conditions had held no terrors for the Australian pilot. ‘When we got engulfed in the blackness of clouds one was able to keep her level with the compass and the bubble.’

Hawker suspected a blockage of the cooling system filter and switched the engine off briefly. This seemed to work, and they flew on for a few more hours but the cooling system problem gradually became worse. President of the Harry Hawker Society, Jim Dale, said Hawker blamed himself for the failure, which resulted from frequent draining and refilling of the water in the radiator. ‘It was before aircraft engines used glycol coolant,’ Dale said. He added that an internal inquiry by the manufacturer Sopwith had concluded the radiator shutter indicator had been connected wrongly, which would have led to the shutters being shut when shown as open. This would have accelerated the cooling problem, Dale said.

In Hawker’s words, ‘We now decided just after 6 am to wander around in search of a ship.’

‘As may be imagined I was not altogether without anxiety although I knew we were right on the steamer route, to which we had taken care to shape our course.’

After two hours of low-level zig zagging, they saw the Danish freighter Mary. ‘We pushed off a couple of miles or so along her course, judged the wind from the wave crests, came round into it and made a cushy landing in spite of the high sea that was running,’ Hawker wrote. The aircraft had jettisoned its undercarriage soon after leaving Newfoundland, which helped with its ditching.

The Mary had no radio and news of their safety had to await its arrival at a Scottish port six days later. During this time, Hawker and navigator Kenneth Mackenzie-Grieve had become the focus of national mourning in Britain, and the subject of a hurriedly written dirge by Banjo Paterson (‘Though Hawker perished, he overcame; The risks of the storm and the sea’).

They arrived, by train, in London as conquering heroes. King George V announced that he would present both men with the Air Force Cross—the first ever personal investitures of the medal. The Daily Mail acknowledged Hawker as the first pilot to fly over 1000 miles (1600 km) of water without touching down and awarded him a consolation prize of £5000. John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown flew the Atlantic on 14–15 June and claimed the Daily Mail prize.

What can we learn from Hawker and Mackenzie-Grieve’s miraculous seeming escape? After 100 years there are few specific lessons and techniques to be drawn from the story. But the overall theme is as clear as ever. Hawker and Mackenzie-Grieve had a plan, and sticking to it, even with the temptation of glory (and the small matter of £10,000) was what saved them. They had, as Hawker said, planned to fly as close to shipping lanes as they could, consistent with a direct course. At the first signs of engine trouble Mackenzie-Grieve had directed the aircraft even closer to shipping lanes and when the engine situation became dire, they responded deliberately with a predetermined strategy of looking for a ship, in the place where ships were most likely to be.

Hawker has one other significant footnote in the history of aviation. Dale confirms he was the first to discover how to recover from a spin.

Hawker died in the crash of a Nieuport Goshawk biplane he was flying on 12 July 1921, but his name lived on until 2013 in the manufacturers Hawker Aircraft, which became Hawker Siddeley, and in Hawker de Havilland Australia and in the merger that created Hawker Beechcraft. Since then, Hawker Pacific, an aircraft sales, aviation operations and services company, has kept the Australian pioneer’s name in the skies.

[…] of well-wishers gathering along their route. Interest in the race to cross the Atlantic was intense after the recent rescue of Australian pilot Harry Hawker. A civic reception was mercifully rescheduled into ‘a short and informal affair,’ and, after 40 […]