Like countless others, a private pilot with decades of experience died when he flew into cloud and became spatially disorientated.

It was no good. The pilot decided to turn back. Low cloud made VFR flight unsafe and he was not instrument rated. But an hour later he took off again, this time flying a more westerly course. Twenty minutes later, the pilot and his passenger, who were brothers, were dead. No one saw their aircraft dive into the ground.

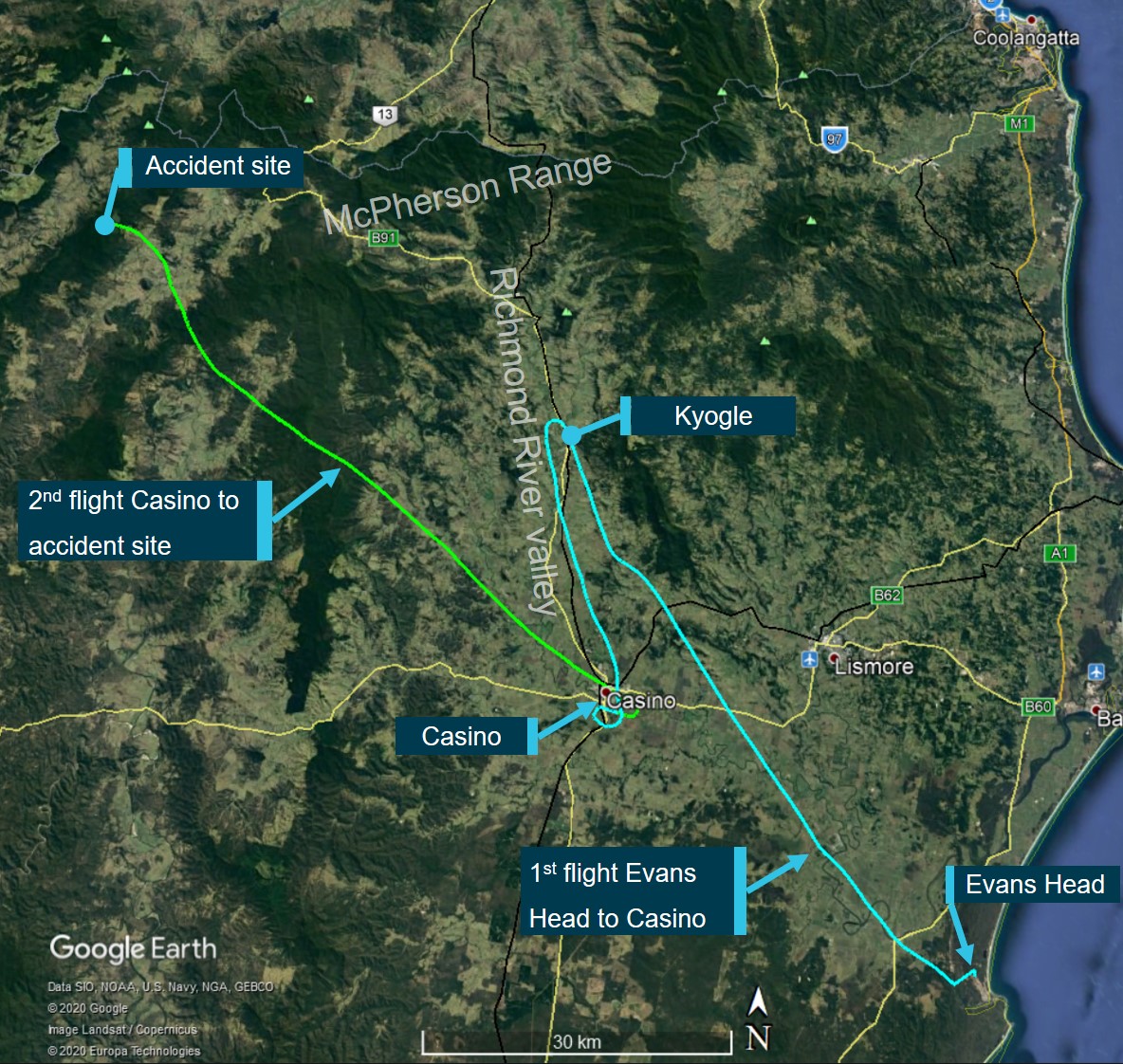

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) issued its report into the crash this week. It happened on 12 January 2020 to a home-built Wittman Tailwind, flown by a 68-year old pilot who had amassed 1200 hours over 38 years. He had built the high-wing, cloth-covered tail dragger over 12 years, and flown it for just over a year after it received its special certificate of airworthiness in the experimental category. The brothers were returning to Boonah, in southeast Queensland from a fly-in at Evans Head in northern NSW. After encountering low cloud ahead the aircraft diverted to Casino, where it remained for an hour before the brothers took off again.

Electronic flight bag (EFB) data showed the aircraft had made a series of rapid descents and climbs followed by a descending left turn that continued until the aircraft collided with high ground in Tooloom National Park, NSW.

Over the last 4 minutes of the flight, the aircraft’s recorded ground speed varied rapidly between 109 and 175 kt, rate of climb and descent ranged between maximum values of +2,400 ft per minute and – 2,400 ft per minute and altitude oscillated between 4000 and 3100 feet.

‘It is likely the pilot encountered conditions of reduced visual cues and became spatially disorientated which led to a loss of control and collision with terrain,’ the ATSB said.

Investigators found the pilot had 8.4 hours instrument flying experience, with 5 of these hours logged in 1982 and 1983, and the remaining 3.4 hours logged from 1986 to 2015. The pilot did not hold an instrument rating.

The ATSB was told the pilot used an EFB for navigation and flight planning but his use was limited to using the direct to function, which plotted a track from the aircraft’s current location to a desired destination. The pilot was also reported to use the EFB’s weather radar overlay function, which displayed rain but did not display clouds.

In discussing why the pilot had chosen to take off again after having turned back, the ATSB report alluded to the inherent difficulty of making correct weather-related decisions. It quoted Australian researchers Mark Wiggins and David O’Hare, who pointed out a paradox.

‘Because of the variable nature of operations in the aviation environment, weather-related decision-making is often considered a skill that cannot be prescribed during training. Rather it is expected to develop gradually through practical experience. However, in developing this type of experience, relatively inexperienced pilots may be exposed to hazardous situations with which they are ill-equipped to cope,’ they said in a 1995 study of general aviation pilots.

The ATSB issued a series of recommendations to VFR pilots, as it has done in many previous reports. These are worth remembering, of course, as is the general, and unsettling message: you are only as good as your last flight decision, and if that decision is weather related, and you are not experienced, you may make errors that you will have no way of dectecting.

Further information

Wiggins, M and O’Hare, D, 1995, ‘Expertise in Aeronautical Weather-Related Decision Making: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of General Aviation Pilots’, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, Vol. 1 No. 4

Comments are closed.