The pilot who landed on the Hudson River, in New York, after a birdstrike disabled both engines in 2009 has spoken out in favour of keeping humans in airline cockpits.

The Germanwings tragedy in the French Alps – where it appears the first officer of an Airbus A320 committed suicide, killing the 149 other people on the aircraft – has even seen some questioning the need to have pilots at all, arguing that humans have always been the weakest link and that greater dependency on automation should see pilots become redundant.

Chesley Sullenberger, has argued that no technology today could possibly replace a pilot’s role, and that such thinking is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of what pilots do and what technology can’t.

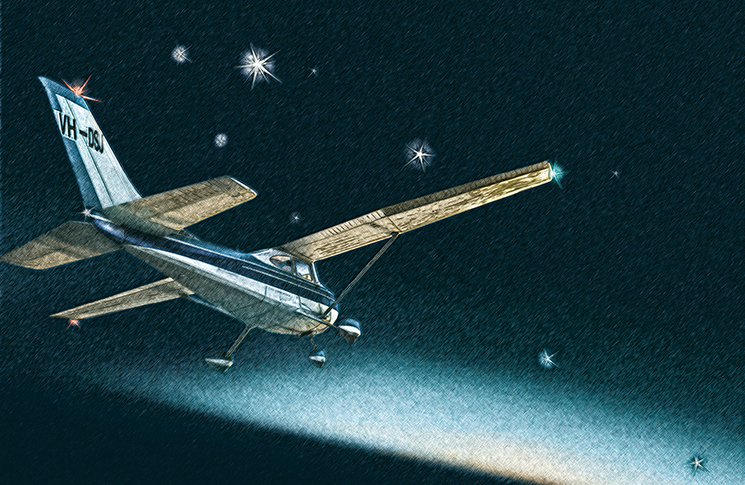

Writing on his LinkedIn blog, he also points out that when his Airbus A320 hit a flock of Canada Geese, it was his human experience that saved the lives of those on board. Sullenberger, first officer Jeffrey Skiles and a cabin crew of three saved the lives of all 150 passengers on USAir flight 1549.

‘I knew from experience there were only two runways near us that might be reachable,’ he says. ‘But I had to be able to look out the window and, from experience on thousands of flights, realise they were a little too far. The only option was the river.’

‘The fact that we landed a commercial airliner carrying 155 people on the Hudson River with no engines and no fatalities was not a miracle, however. It was the result of teamwork, skill, in-depth knowledge, and the human judgment that comes from experience,’ he says. ‘To this day, I know of no technology, even on the horizon, that could have done what we did.’

Sullenberger argues that teamwork between pilots make a human system ‘more robust, resilient, and reliable than the sum of its parts.’ With technology however, he argues the opposite is true.

‘The more layers piled into increasingly complex systems, the more failure paths we introduce. We’ve learned that automation does not eliminate errors. Rather, it changes the nature of the errors that are made, and it makes possible new kinds of errors’, he says.

Sullenberger argues that while there is no silver bullet, the best system will be the integration of both human and automation, with technology providing decision aids and safeguards, while leaving the active roles to the pilot.

With air transport crashes now rare and complex events, Sullenberger cautions against kneejerk reactions that seek to prevent future crashes by imposing the solution to the most recent accident ‘…could technology have prevented the terrible Germanwings crash that killed all 150 people aboard?’ he writes. ‘Perhaps. Would it also help prevent the next unanticipated event? Probably not.’

[yop_poll id=”8″]

In a previous Flight Safety Australia story, we asked you what your thoughts were on greater automation and the potential of having just one pilot in the cockpit. At the time of writing 85% of readers were against the idea, fearing that over-reliance on automation has worrying safety implications.

Captain Sullenberger is correct in his general summary of the benefits of human experience in the cockpit versus complete automation.

But, the two view represent the opposite extremes of the argument.

The best solution probably lies somewhere between these two extremes. No pilots, versus pilots in the cockpit is not the real argument. We know it is absolutely possible to fly an aircraft, a complex large aircraft, from a remote cockpit using the team skills of experienced pilots just as though they were both actually in the cockpit of the aircraft. The only difference between this and the extreme of ultimate and soloe control by pilots in the cockpit on board the aircraft, is that there is a telemetry link between the remote pilots and the aircraft whereas with the pilots on board, no such link is required although for many of the piloting functions, probably already exists, albeit contained on the aircraft.

It can of course be argued that the cost of remotely piloting all aircraft is simply far, far, too expensive. The bandwidth required for the necessary telemetry is simply not currently available, and would only be available in the future at a simply outrageous cost. A cost which airlines and regulators are unlikely to ever accept.

But there is yet another in between solution, and that is to have on-call at all times, qualified crew in appropriate cockpits at various remote locations who could at a defined point in an emergency situation, assume complete control of the aircraft rendering the on board pilots excuded from the control loop. The airlines themselves could be responsible for such facilities for each of the aircdraft types they fly.

Such a facility would be activated only where necessary for the successful completion of a flight where control of the aircraft by on-board pilots has for some reason been lost. The Germanwings event could be cited as an example of just such a case.

Rapid transition to an “emergency” crew at a remote location as soon as an emergency situation is recognised would be the requirement.

This concept represents minimum cost to oeprators as incidents where on board crew effectively lose control of the aircraft are to date, relatively rare. But the cost of such an event in both human and financial cost terms is great enoough that much consideration should be given to the concept.

Pilots have first priority, automation must always be aids to pilots.

How are you going to (a) afford and (b) keep current and checked in all phases of flight a team of ground based standby pilots scattered in ‘cockpits’ around the country for the one in probably a million occasions they would be needed. Let alone construct a flight deck with remote control capability. And constantly maintain remote control certification. We know there is a limit to how long a human can simply act as a monitor. How would these standby pilots be kept motivated and maintain job satisfaction when nothing happens year in and year out? It would be cheaper to modify future reasonably sized aircraft to have a toilet enclosed within the boundary of the cockpit so a pilot never has to leave the flight deck. Some airline 747-400’s already have this ‘ensuite’.

Probably off subject and with the wisdom of hindsight I always wonder why the crew on the Hudson River incident never gave more attention to restarting the engines. True time was at a premium but until the moment of impact I would be concentrating solely on getting one of the brutes going!

It was difficult to ascertain if this was or wasn’t done reading through the reports but I just had that feeling they were committed to a river landing before all else…………………. but I’m off subject I fear and will leave you with the thought……………..

Give the crew some credit, please! The reason the engines stopped is the reason they can’t be restarted. Of course they would have tried but there was physical damage, firstly to the bypass fan blades and then probably ripping out the accoustic lining inside and perhaps after the birds had been roasted, bits of them damaged the high spinning turbine blades on the way out all causing enough vibration to shake the engine from its pylon mounting. Tens of thousands of hours experience and knowledge in that cockpit.