The new Risk Radar Aviation (RRAv©) aims to help Sport Aircraft Association of Australia (SAAA) members fulfil the Association’s aim to: ‘Plan wise, build well and fly safe’.

Four years ago, the SAAA launched an innovative analytical tool to flag potential issues for amateur aircraft builders, helping them to measure their competence as builders/pilots against their peers, as well as against national and internationally recognised aircraft build and maintenance standards.

Flight Safety Australia profiled the risk radar in our November-December 2013 issue. In the intervening years, despite what SAAA owner/builder of an RV8a completed in 2007, and risk radar developer, Andy George, describes as ‘enthusiastic uptake in some quarters’, the risk radar did not enjoy the support it deserved.

However, that has changed. Driven by George and John Smith—around planes all his life and regularly flying his Lancair Legacy, completed in 2010, the two worked to develop a new improved version of the original tool for the SAAA, which was launched at OzKosh 2016. Like George, Smith’s professional career also included exposure to risk management, in his case, in the oil and gas industry.

Now titled Risk Radar Aviation (RRAv©), the new risk radar has been expanded to cover project selection, more on the build, a larger test flying section, and now also includes ongoing flying and maintenance. As George explains, ‘Traditionally, our SAAA focus has been on the build, the flying side of things hasn’t had as much coverage, which is why we have developed that more in the new risk radar.’ George says that the risk radar is about ‘getting people to slow down, and think carefully about human errors and weaknesses’. Smith adds, ‘In a nutshell, it’s simply about managing risk (to do that) … first you have to be aware of what the risks are, how important they are, and then do something about them. We all do this intuitively every day of our lives. When we’re crossing the road, for example: almost instantly, we assess the situation (Is there a pedestrian crossing? How much traffic is there? Can we see the traffic? How fast is it going?) and decide when to walk, or not. But the huge difference is that most of us simply do not build and fly planes every day of the week.’

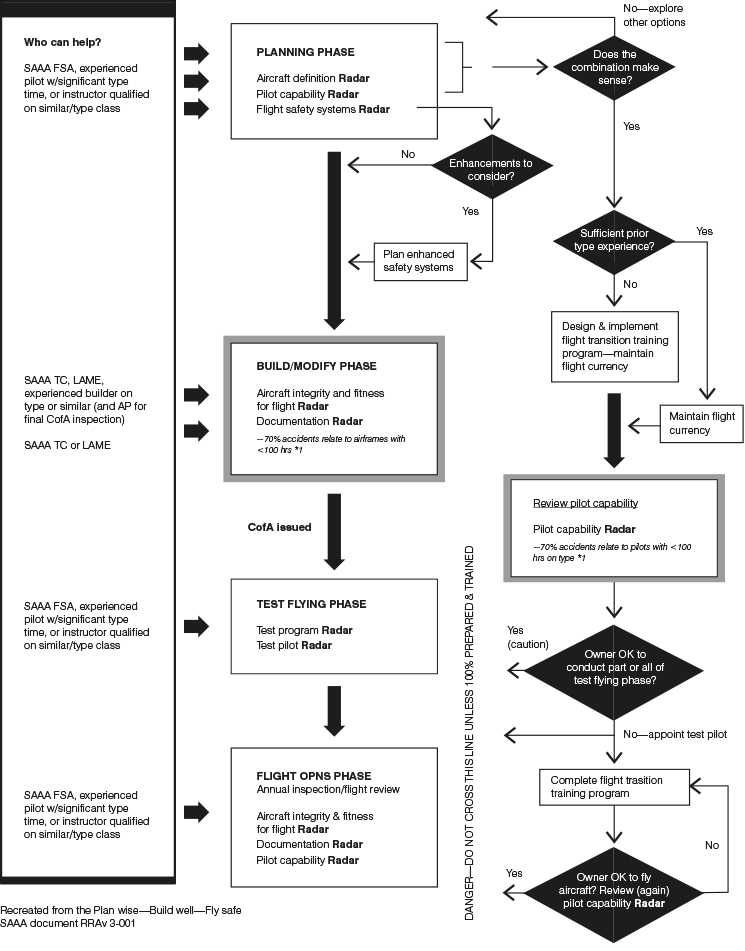

RRAv covers every aspect of building and flying an aircraft: from deciding what aircraft to build, building/modifying that aircraft through testing, and finally, routine flight operations and maintenance. The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) Experimental Aircraft Category Accident Statistics Review 2002–2012 gives some stark numbers:

- approximately 70 per cent of accidents occur with fewer than 100 pilot hours on type

- approximately 70 per cent of accidents occur with fewer than 100 hours on airframe time.

‘Clearly, the statistics tell us we must and can do better.’ But as Andy George succinctly puts it, ‘If statistics are not your thing, or you don’t want to think about them, just remember—don’t be sitting up there wishing you had done something better in your planning, build or training.’

Similar to the earlier risk radar, RRAv presents the data about the various stages of building and flying your experimental aircraft in ‘nice, simple, graphical representations’, so that the owner/builder can see their progress immediately. Once owner/builders have installed the system on their computer, RRAv accepts the builder/pilots inputs at various stages of the build and flying phases and graphically represents how he or she compares to his peers and international standards. It is as Smith describes, ‘an unemotional measuring tool’ to help you track your progress.

RRAv covers four distinct phases—planning, build/modify, test flying and (routine) flight operations. You can enter the program at any point, depending on whether you are starting with a fresh build, picking up a part-completed build, or purchasing an already completed aircraft. According to Andy George, ‘there are 3500–4000 combinations in the RRAv, which has been beta-tested against various builds. Nobody’s likely to score 100 per cent.’

Within each of these four phases, RRAv addresses a number of sections ranging from aircraft definition (design and performance etc.), pilot competency, aircraft documentation, aircraft integrity and fitness for flight, test flying plans and test pilot competency; and ongoing aircraft integrity (annual inspections) and pilot competency (flight reviews). Each section contains a number of criteria that can be rated or benchmarked using a combination of consistent, practical and recognised standards.

These measures result in a graphical representation that provides a picture (risk radar) for example:

- showing whether a proposed aircraft/pilot combination ‘makes sense’. This planning phase radar examines the design and performance of the aircraft you are proposing to build. Some aircraft are obviously more of a handful to fly than others, so how ready are you to fly this aircraft?

- defining the basis of a flight transition training program. Test flying is where there is the highest level of risk

- identifying how complete your aircraft documentation is

- assessing the build environment (workshop, tooling, support etc.)

- showing shortfalls or potential areas for improvement in a build

- showing pilot capability (pre-build, post-build and/or transition training).

The rating process is not an exam or an indication of failure. Simply, if something doesn’t quite stack up, or can be improved, it simply raises a flag, saying in effect, ‘Hey—this doesn’t quite measure up to industry standards (trade skills or flying). Please rethink, or ask for help and guidance.’

The new RRAv also provides a way to submit various one-off and periodic reports such as: technical councillor (TC) build reports, certificate of airworthiness, annual inspection and flight review reports. The builders and technical councillors forward auto-generated reports, enabling data to be collected about common issues builders share, such as engine installation, or the number of flying hours on type. By collecting, collating and interpreting such data, safety improvement initiatives, for example, specific training needs, can be identified and implemented.

With a build that has reached CofA status the builder presents his signed RRAv to the Approved Person in his suite of documents to gain that coveted CofA and is used by the AP in framing his Phase 1 test flying phase approval.