By the time you read this, a few hundred Australian travellers will be settling into the local timezone in London, and other European locations, ideally with less fatigue than usual. They were the first passengers on Qantas’s Perth-London non-stop service.

The rest of aviation may in time get to share in their bright-eyed good fortune: a clinical trial is measuring how long-haul flying can affect your health. In a world first, Qantas is collaborating with the University of Sydney’s Charles Perkins Centre to better understand the effects of long distance travel on passengers.

At just under 8100 nm (15,000 km), it is one of the longest routes in the world—a 17-hour non-stop journey flown by a Boeing 787-9 Dreamliner. It’s a sharp comparison to the original ‘Kangaroo route’ pioneered by Qantas that had seven stops and took four days.

Many months of clinical trials are planned with Qantas frequent flyers fitted with wearable technology to measure mental state, anxiety levels, immune function, sleep and jet lag recovery. Headed by Professor Stephen Simpson from the Charles Perkins Centre, which researches lifestyle diseases such as obesity and diabetes, the goal will be to find ways to improve the comfort of passengers on long-haul flights.

‘We have a long way to go in terms of understanding how the wide variety of influences—including nutrition, hydration, exercise, sleep and light—might work together for maximum benefit,’ Simpson says.

Passengers will need to be patient. Simpson has predicted that it will take many flights and many months to make ground-breaking discoveries on the biggest bugbear for long-distance fliers—jet lag.

However, Simpson’s team has already designed a system for Qantas to make cabins conducive to changing our circadian rhythms, including lowering and raising temperatures and adjusting the wavelength and strength of light. ‘To the naked eye, the lighting (on board) appears entirely natural, reflecting the various cycles of sunrise, daytime, dusk and night passengers would be used to on the ground,’ explains Philip Capps, head of Customer Experience at Qantas.

Food and the timing of meals on these flights will also change with long-time Qantas culinary partner Neil Perry designing menus using foods that are known to stimulate the production of melatonin, a hormone linked to sleep and biorhythms, as well as containing ingredients that will increase hydration. This means that dishes will be less spicy, lighter with less protein and topped off with probiotic drinks and coconut water. Fancy a raw fish salad served with sesame soy dressing; seared barramundi with garlic potatoes, broccolini and olive and almond salsa; or poached egg, kale, quinoa, grilled haloumi and tahini dressing? Well, you’ll have to fly business class. Economy passengers get tomato and mushroom puff pastry tart and corn salsa; marinated beef, cumin and zucchini salad; and roast chicken with red rice and mediterranean vegetables.

‘Qantas’s new menu incorporates the latest scientific knowledge on nutrition and hydration and our scientists are excited by this opportunity to discover how the wide variety of influences work together during long-haul flights,’ Simpson says.

Other modifications to the Dreamliner include wider seats with extra leg room and windows that are 65 per cent larger than those of conventionally constructed airliners. Dimmer switches, rather than shades, mean you can still look out the window while other passengers are watching their entertainment screens.

Qantas is already flying the Dreamliner between Melbourne and Los Angeles, and will use the aircraft for direct Melbourne-San Francisco flights from September.

According to Boeing, the Dreamliner’s composite body is stronger than aluminum aircraft, so it can withstand greater air pressure in the cabin—closer to the experience of being on the ground. The Dreamliner is pressurised to an apparent altitude of 6000 feet rather than the usual 8000 feet. The inherent corrosion resistance of its composite fuselage allows the air to be more humid, which should reduce the headaches, dizziness and fatigue associated with mild dehydration from hours of breathing dry air.

This is not the first time Qantas has flown an long and pioneering route out of Perth, but today’s passengers, with their personal music players and choice of movies, fly in luxury inconceivable to their counterparts of 75 years ago.

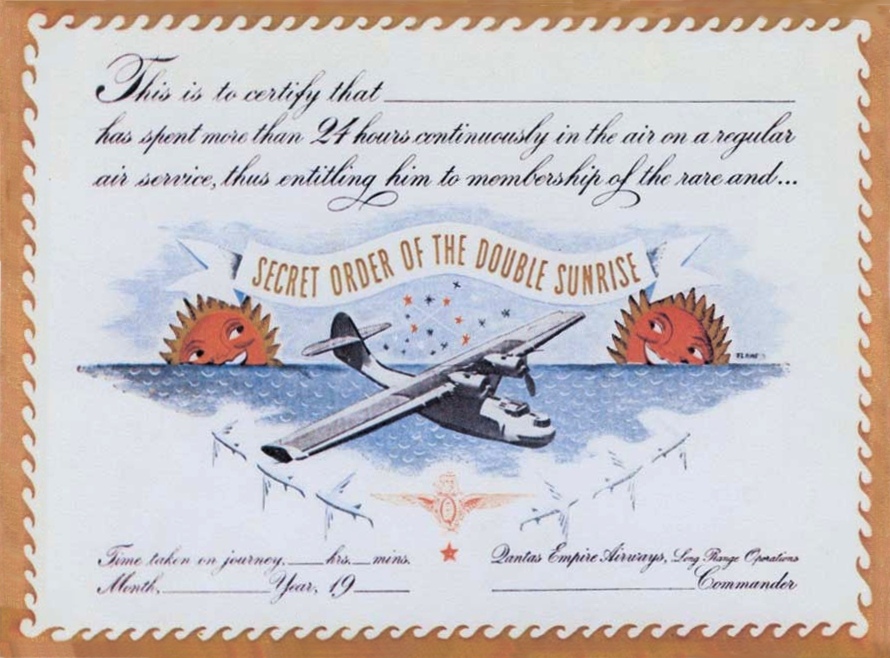

Between June 1943 and July 1945 Qantas flew Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats between the Swan River at Nedlands in Western Australia across the Indian Ocean to Koggala Lake in Ceylon, now Sri Lanka. The purpose of the flight was re-establish the Australia–England air link that had been cut due to the fall of Singapore during World War II.

The Catalinas flew non-stop for between 27 and 33 hours, crossing Japanese occupied territory during darkness. Passengers and crew would observe the sunrise twice which led to the service being called ‘The Double Sunrise’ by the few who knew of its classified existence. To get its Catalinas to fly 3580 nautical miles (6630 kilometres) Qantas operated them at a gross weight of 16,000 kg, 4000kg heavier than the published MTOW. All superfluous weight including sound insulation was stripped from the cabin, and for weight and balance reasons the three passengers (fewer than the five crew) had to crouch in the bomb-aimer’s position in the nose for take-off. Here they were often drenched as waves broke over the nose early in the take-off run.

Qantas developed its own take-off technique to get the grossly overloaded flying boats off the water. To avoid prevailing westerly winds, flights out were restricted to altitudes below 2000 feet, making navigation a severe challenge. Return flights flew higher, up to 10,000 feet, to take advantage of the westerlies.

The recently published Courage in the Skies by Jim Eames records that an official from the Department of Civil Aviation described the proposal as ‘little short of murder,’ in a memo strongly recommending against it. But Qantas never lost a double sunrise aircraft, despite experiencing six engine shutdowns in 271 flights, and an encounter with a Japanese patrol flying boat. ‘I think he was just as scared and anxious to get away as I was,’ the Qantas pilot later said. The double sunrise flights still hold the record as the longest non-stop airline flight, measured by time.

The Australian airline had overcome doubters, and by a combination of planning, expertise and attention to detail had flown near the limit of practical operations with unblemished safety. You might say there’s nothing new under the sun.