It seems absurd that something as simple as changing your sitting posture in a vehicle travelling at up to 1200 km/h groundspeed could make a difference to your odds of surviving a crash, but the results are in. The brace position works, and you will do yourself potentially a very great favour by knowing how and when to adopt it.

Cynics might say that nothing you do or don’t do will make any difference in an impact at cruising speed, and they’re right. But the majority of aircraft accidents happen at much slower speeds, typically well under 200 knots, in landing crashes. At these speeds the brace position has been shown to make a difference.

A memorable anecdote comes from the sole survivor of Downeast Airlines flight 46, a DHC-6 Twin Otter flying from Boston to Rockland, in the US state of Maine, in 1979. The sole survivor of the crash was a 16-year-old boy who recalled waking up, seeing trees through the window, and adopting a brace position.

From a National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) report: ‘There was no pre-crash warning, and most of the passengers were sleeping or reading. When the survivor saw that the aircraft was going to crash into trees, he immediately lowered his head and braced his arms and knees against the seat back in front of him. Although his seat, along with most of the other seats, separated upon impact, he suffered only a fractured leg and wrist and a scalp wound.’

THE NTSB mentions two other times when braced passengers fared significantly better than unbraced ones.

An Atlantic City Airlines De Havilland DHC-6 Twin Otter crashed while on an approach to Cape May County Airport, New Jersey, on 12 December 1976. Eight passengers and two crew members were on board. The co-pilot and three passengers died. One 19-year-old male passenger, seated in the second row of seats, had lowered his head between his legs because he was airsick. He reported there was no warning before the crash. He sustained minimal injuries while the three passengers seated beside him and in the row in front of him died from crash trauma to the head and chest.

A DHC-6 Twin Otter crashed into snow-covered mountainous terrain near Steamboat Springs, Colorado, on 4 December 1978. The captain and one passenger died from crash injuries while the first officer and 13 other passengers received serious crash injuries. No crash warning was given to the passengers. One 26-year-old female passenger, seated in the centre of the passenger cabin, took a brace position because she was frightened and suffered only minor bruises and abrasions. Several other passengers seated around her suffered significant head injuries, including skull fractures, lacerations, and concussions.

The brace position has been refined over the years, with a significant revision happening after the crash of British Midland flight 92, near Kegworth, England, in 1989. Analysis of the injured survivors found many of them had lower limb injuries, and the brace position was changed to try to minimise these. Since 2016, the International Board for Research into Aircraft Crash Events (IBRACE) has brought together engineering, medicine and human factors experts for the purpose of producing an internationally agreed, evidence-based set of impact bracing positions for passengers and cabin crew members.

CASA Cabin Safety Bulletin No.6 covers the brace position for aircraft passengers and crew. The bulletin covers forward and rear-facing seats, what not to do, what to do with children and infants, and people with disabilities and their companions.

The brace position is the most effective protective position for passengers and crew to adopt to reduce the chance of injury during an aircraft crash. But it has changed over the years. ‘As seat technology has evolved so have effective brace positions and previously recommended positions may need to be adjusted,’ the bulletin says.

Avoidable injuries in passenger cabins during crashes come from two mechanisms—flailing, in which the limbs move out of control, and secondary impacts with parts of the cabin, such as seat backs.

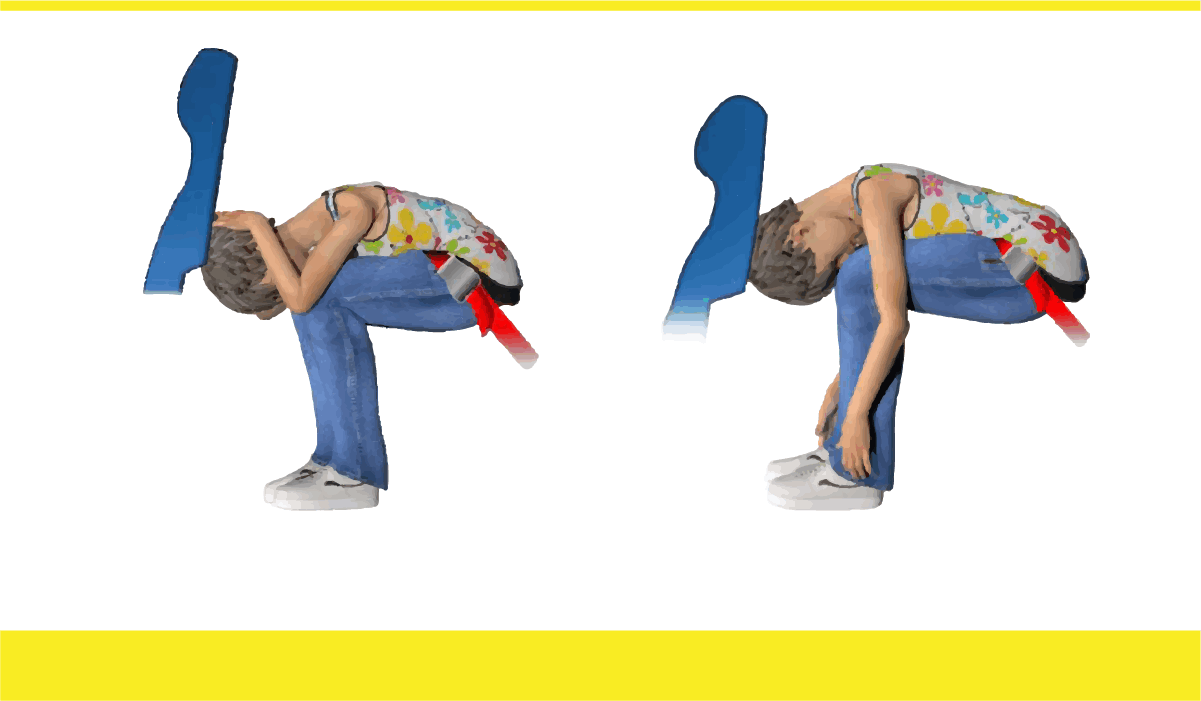

The brace position reduces flailing by having a forward-facing occupant lean over their legs and it reduces secondary-impact injuries by pre-positioning the body against a surface that can be struck. This reduces the momentum of the head and other parts of the body.

The most appropriate brace position may vary according to seat orientation, different seat belts or cabin configuration. There are a number of positions to avoid when bracing, such as stretching out arms or legs and resting the head on arms or hands.

In a forward-facing passenger seat fitted with a lap strap seat belt only, passengers should brace according to the following instructions:

- Sit as far back as possible

- Fasten seat belt and tighten firmly, low across the hips to prevent submarining (when a passenger slides forward under a loosely fitted seat belt). The seat belt should not be twisted

- Tuck chin onto chest

- Bend forward (‘roll up into a ball’)

- Place head against the seat in front

- Place hands on top of head

- Place arms at sides of lower legs or hold lower legs (holding onto the lower legs may provide a more stable position)

- Place feet flat on the floor, as far back as possible

- If passengers are seated at a bulkhead row or cannot reach the seat in front:

- bend forward and place hands on top of head

- bend forward and place arms at sides of lower legs or hold lower legs.

Children

ICAO recommends infants and children who weigh less than 26 kg and whose height is less than 125 cm should occupy an approved child restraint system (CRS) on board aircraft, in a seat of their own.

Using a child restrain system provides infants and children with an equivalent level of safety to adult passengers wearing seat belts. Children occupying approved child restraint devices should brace in accordance with the device manufacturer’s instructions.

Generally, children occupying a passenger seat should use the same brace position as adults as appropriate to their height.

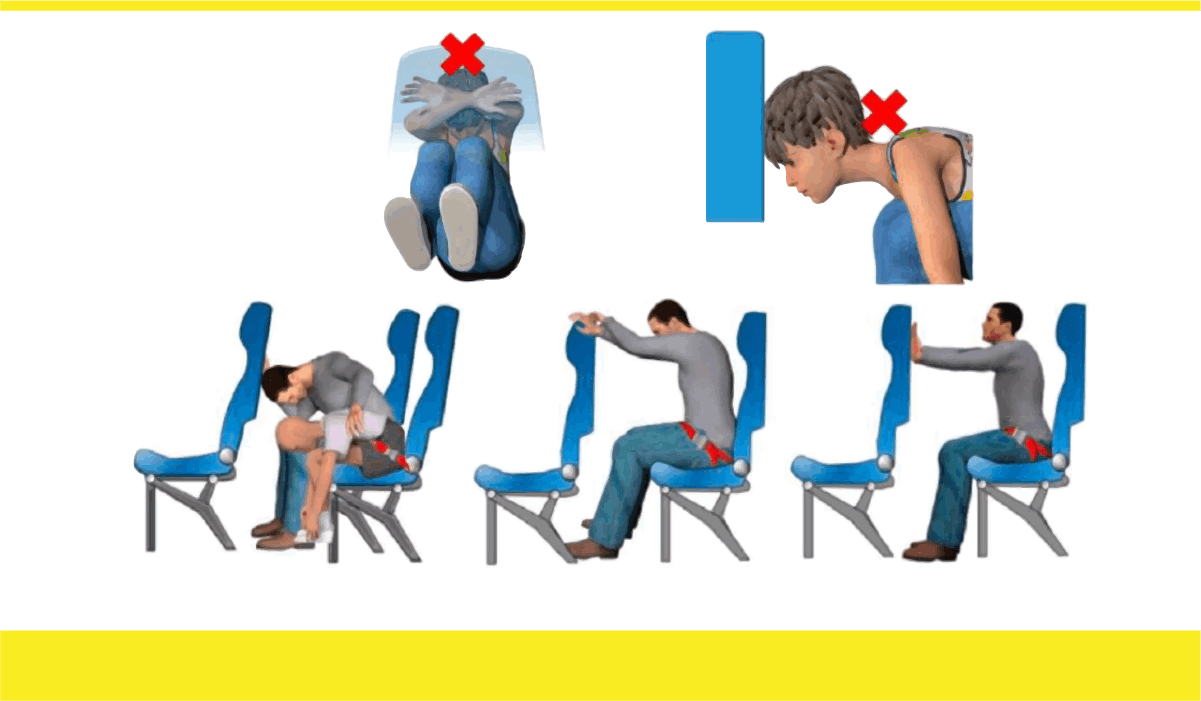

What not to do

You should avoid certain positions that may cause injury to the neck and/or larynx. Also, do not rest your head on crossed forearms or your hands, as you risk fracturing both forearms and/or both hands and fingers.

Other positions to avoid:

- Do not remain in an upright position, without prepositioning your body, predominantly your head, against the surface it would strike during the secondary impact.

- Do not stretch out your arms or legs and press them against a surface in front of you.

- Do not try to physically restrain a child or another passenger in an adjacent seat or assisting another person in maintaining a brace position, as this may increase the risk of injury.

Comments are closed.