The music of Buddy Holly is everlasting, and so, unfortunately, is the type of aircraft crash that killed him.

Sixty years ago, on 3 February 1959, Holly, fellow rock ‘n’ roll pioneers J. P. Richardson and Richie Valens were killed alongside 21-year-old pilot Roger Peterson, when a Beech 35 V-tail Bonanza crashed near Mason City, Iowa, in the US, about 1 am local time.

The US Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) report tells a sadly familiar story: pilot spatial disorientation followed soon after by impact with the ground.

‘This accident, like so many before it, was caused by the pilot’s decision to undertake a flight in which the likelihood of encountering instrument conditions existed, in the mistaken belief that he could cope with en route instrument weather conditions, without having the necessary familiarisation with the instruments in the aircraft and without being properly certificated to fly solely by instruments,’ the CAB’s report says.

However, like the great majority of aircraft crashes before and since, the tragedy had several contributing factors.

Pilot

Peterson was not an instrument rated pilot. He had had about 52 hours of dual instrument training and had passed the instrument written examination but had failed an instrument flight check in March 1958. He and the charter company he worked for were only authorised to fly VFR.

Weather

Peterson seems to have been aware that a successful flight would only be possible under night VFR conditions. The fact that his boss, the aircraft owner, watched the aircraft until it disappeared also suggests a certain anxiety. Peterson had checked the weather several times, beginning at 5:30 pm, and making his last check while taxiing to the runway. The ceiling was at first reported at 5000 feet or higher, with visibility of 10 miles or more. At take-off, the local weather had deteriorated to a reported precipitation ceiling at 3000 feet, sky obscured, and visibility of six miles. Light snow had begun to fall, with 20 knot winds, and gusts to 30 knots.

The weather briefers did not tell Peterson about flash weather advisories issued before take-off that described deteriorating conditions en route that included visibility below two miles, freezing drizzle, and moderate to heavy icing below 10,000 feet. The CAB report said, ‘The weather briefing supplied to the pilot was seriously inadequate in that it failed to even mention adverse flying conditions which should have been highlighted.’

Human/machine interface

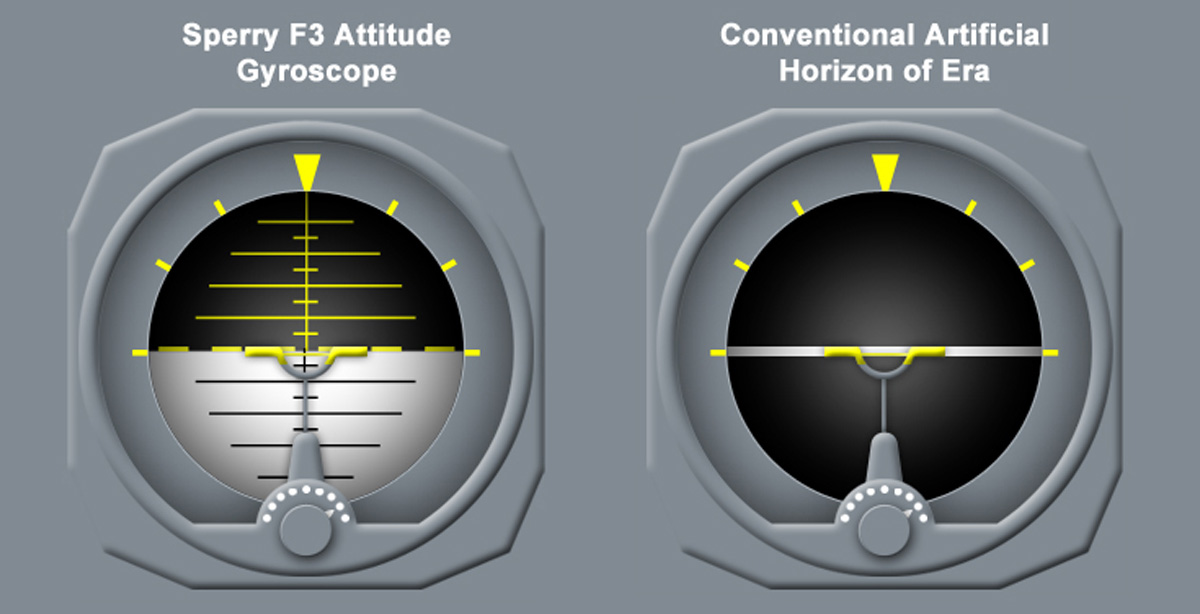

The Bonanza that Peterson was flying that night had a Sperry F3 attitude indicator. This instrument displayed pitch information very differently to the white-line-on-black artificial horizons in use at the time. The F3 display was in two colours, like modern attitude indicators. However, the upper half of the F3’s display was black, and the lower half was white, unlike modern displays that use blue to represent the sky and brown to represent the unforgiving earth. Also, the F3 indicated pitch in the opposite direction to conventional and modern indicators. A nose-down attitude on the F3 would be indicated by the upper black section becoming larger.

The CAB concluded, ‘the pitch display of this instrument is the reverse of the instrument he (Peterson) was accustomed to; therefore, he could have become confused and thought that he was making a climbing turn when in reality he was making a descending turn.’

The Bonanza had recently been fitted with an autopilot, but this was not connected at the time of the crash.

Fatigue

The flight had been organised at short notice because musicians on the Winter Dance Party tour were tired of long overnight bus journeys between venues in the below-freezing weather of the US Midwest in January. (A drummer suffered frostbite on a bus with a failed heater.) Peterson accepted the assignment about 5.30 pm. Had he risen at a normal hour that morning he would have been awake for up to 19 hours at the time of the crash. This is not mentioned in the report.

Legacy

Buddy Holly’s short life gave the world the template for rock music. A young Bob Dylan saw him in concert, and he was a major influence on the Beatles. It’s a pity that the cautionary story of how he, Richardson, Valens and Peterson died has been less influential on aviation. Spatial disorientation continues to kill, always unnecessarily.

So trust your instruments, avoid darkness and cloudy weather if you are not instrument rated and recent, read up on spatial disorientation and remember that it is no respecter of pilot experience. Our aim should be to eliminate it as a killer of pilots and passengers. That’ll be the day.

Comments are closed.