by Stephen Cooper, a Flight Safety Australia reader

Today’s mission was to be a four aircraft simulated attack on HMAS Perth sailing 140 nautical miles from the NSW coast.

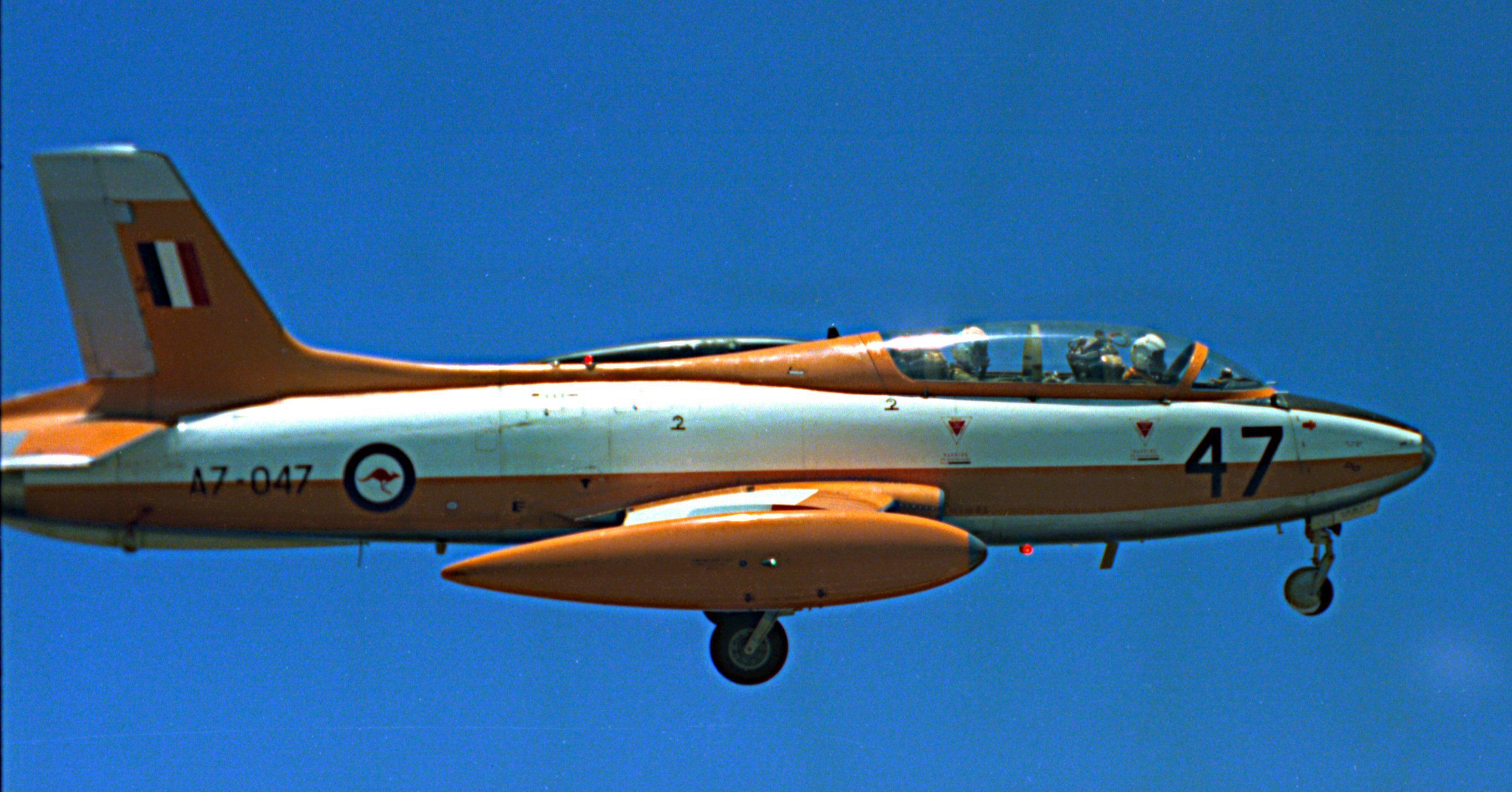

We would be flying the strike at not above 50 feet from the water to evade radar detection by the ship, to make it a realistic, wartime attack for them. I was to fly solo in my Macchi, as number two in the formation, whereas the other three aircraft would be two up. We would be flying in close formation until we reached a predetermined position on the coast. Then we would take up our individual headings calculated by me, to reach points on an arc around the destroyer. From there we would turn inbound to arrive over the top of the ship simultaneously, making it more difficult for HMAS Perth to engage all of us at the same time.

The CO, who was leading the formation, called ready at the holding point. The tower responded, ‘Delta Reds cleared for take-off, contact departures on button three airborne’. The CO read back, ‘Delta Reds, cleared for take-off’. We then lined up on the runway and I positioned my Macchi a few metres away from the CO, tucked in on a 45-degree angle. Red One then gave the wind-up signal to increase to 100 per cent power, made a visual check of the other aircraft and then released his brakes. We accelerated rapidly along the runway as I made small adjustments to the controls to stay in echelon left position. The lead aircraft then called, ‘Delta Reds button three go’. Then transmitted, ‘Departures, Delta Reds climbing through 1400 feet tracking 095 degrees’. Departures replied, ‘Delta Reds identified’.

Delta Red aircraft Three and Four then formed up in echelon left of me and we climbed quickly to 4000 feet. Leaving the coast, the CO called the ship, ‘Perth, Delta Reds inbound’. HMAS Perth replied, ‘Delta Reds, change of requirements, would you attack in line astern from the west, followed by a second attack from different points of the compass’. The CO responded, ‘Perth, Roger’. Then ‘Delta Reds tac formation, line astern go’. I reduced power as did Delta Red Three and Four and we adopted positions 150 metres behind each other. The lead aircraft then began descending and we levelled out just below 50 feet above the waves. The horizon was obscured by low cloud and mist and the visibility was reduced, so I concentrated hard on maintaining my formation position and height. Our speed was some 300 knots as we tore along, and the sensation was exhilarating. Twenty minutes later the formation streamed over the ship and the CO, called, ‘Delta Reds echelon left go’. I advanced the throttle to full power and closed up on the lead aircraft. Neatly in formation the CO began navigating the group into position for the subsequent attack. Despite the low altitude and the concentration required to maintain a close formation position, my thoughts began to wander back to the previous night, which I had spent in the company of a most beautiful lady.

Consequently, I failed to keep track of our headings while transiting into position for the next attack. I became somewhat disorientated and when the CO transmitted, ‘Red Two anchor, 092’. I was confused as I thought the ship was in the opposite direction. I queried the CO ‘Red Two say again’. The CO replied somewhat tersely, as he didn’t want to prolong the transmissions, enabling HMAS Perth to fix our position. ‘Red Two 092!’ I checked my TACAN navigation needle, which was tuned into the ship and that was swinging lazily but seemed to indicate that the ship was to the east. I therefore assumed that my inbound heading was 092 degrees. Unbeknown to me, the CO had given me a radial bearing from the ship. The other aircraft were dropped off to anchor by the CO in different positions awaiting the call to turn inbound by the lead aircraft.

A few minutes later the CO called, ‘Delta Reds, turn inbound’. I adopted a heading of 092 degrees and increased my speed back up to 300 knots. At such a low height and with reduced visibility, I didn’t expect to sight the grey painted ship until within a few miles of it. I wasn’t worried therefore when I was approaching bingo fuel state and had still not seen the ship. The time I had calculated for the 40 nautical mile inbound run came and went and I started to become concerned. A few minutes later, I heard a faint radio transmission, ‘Red Two come in’. The broadcast sounded like it was coming from a long distance away. My fears confirmed, I advanced the power to 100 per cent, began a turn to the coast and commenced climbing. I then called, ‘Perth, Red Two’. The CO replied before HMAS Perth responded and asked for my inbound run heading. I responded, ‘Red Two, 092 degrees’. The CO then called, ‘You were heading for New Zealand!’ He further transmitted, ‘We have a MAYDAY situation on our hands’.

I continued climbing rapidly as the ship radar identified me and gave me a heading at my request for the airstrip at Jervis Bay, the nearest aerodrome. The rest of the formation were returning to our departure point at HMAS Albatross, while I experienced a transient sinking feeling in my stomach when I realised that I didn’t have enough fuel to make it back to land. My first thought was that I would have to fly back over the top of HMAS Perth and eject. After due consideration, I determined that if I climbed as high as possible, I may be able to glide to Jervis Bay, without power. I then adopted this as my course of action. The Macchi carried a fuel load of 2400 pounds and I was rapidly approaching this figure, according to the fuel-used meter. At 2400 pounds consumed the engine was still running. 2405, 2406, 2407, still turning, 2408 pounds and the engine flamed out and began to wind down. I took up the recommended gliding speed of 140 knots and continued down. I was still some 50 nautical miles from the coast, where the airfield at Jervis Bay was located.

Approaching the coast at 5000 feet I was still unable to see my destination airfield as it was obscured by 7/8’s cumulus cloud, with a base of 2000 feet. With the airfield still not visible, I decided that I would dive through the cloud cover and if I could glide to the airfield, I would land at Jervis Bay, otherwise I would pull up and eject over the land.

I determined that I was almost over the field and was about to nose over when through a small hole in the clouds I saw the white letters 15. I then transmitted excitedly, ‘Red Two I have the airfield in sight, I have the airfield in sight’. I was asked to say again, and I responded with the same message, somewhat more calmly. The senior pilot, who was in the Nowra tower to provide support transmitted, ‘Just like in training and don’t worry about gear or flap speeds’.

As I emerged through the gap in the clouds, I found myself located at ‘High Key’ at 1500 feet and 220 knots. The profile for a forced landing at this position was 2500 feet and 140 knots. I held my height and circled around to ‘Low Key’, with my speed reducing to the profile speed of 140 knots at the correct height of 1500 feet. From this position I selected gear down and half flap. It was then a simple matter to glide around onto final approach, select full flap and touch down smoothly on Runway 15.

The flight was over.

So, what did I learn?

The main lesson that I learnt from this experience was to keep my mind on the task at hand while aviating and not be distracted by external events. It is also advantageous to ensure that you are well rested before undertaking a flight, which was not the case in this instance. In addition, considering the consequences of taking up the incorrect course, I should have clarified my inbound heading with the CO to remove confusion.

The most valuable piece of advice that I have been given while undertaking flying training is to, ‘trim and relax’. As the successful conclusion to my flight demonstrates, it pays to stay calm in an emergency situation and consider all options at hand.

Terms

Bingo fuel: The fuel state calculated that is required to return to base from the ships position with the required fuel reserve of 300 pounds remaining.

High Key: A position abeam the touchdown point on the upwind leg at 2500 feet and 140 knots in the forced landing pattern.

Low Key: A position abeam the touch down point on the down-wind leg at 1500 feet and 140 knots.

Comments are closed.