With the help of a historian who researched the subject over four decades, and a former politician turned award-winning writer, Flight Safety Australia re-examines a crash that decapitated Australia’s wartime government.

By Robert Wilson

1940 There was a war on. British and German fliers were shooting each other down over the skies of southern England in a summer of death that would later be called the Battle of Britain, and it was still conceivable that Nazi Germany might invade the British Isles. Australia was in its first winter of what would surely be a long, grim but distant struggle.

At 9.30 on the morning of 13 August, a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Lockheed Hudson took off from Essendon, Melbourne, on a flight to what was then emphatically Australia’s bush capital, Canberra. Parliament house stood amid open paddocks and the local airport was an all-over field, with no runways but a clay landing area.

On board the aircraft were 10 people: three cabinet ministers, the Chief of the General Staff and his liaison officer, the private secretary to the Minister for Air and four RAAF crew.

In Canberra it was a cool clear day with a 15-knot wind from the north-west. Shortly before 11am the Hudson arrived and flew a left-hand circuit, passing over Queanbeyan on base leg and over a low rugged ridge on final as it approached the airfield from the east. For no clear reason, it went around for another circuit.

RAAF Pilot Officer Raymond Winter was watching. An experienced pilot, he would tell a RAAF Court of Inquiry two days later how he had thought the Hudson’s pilot was flying with above-average airmanship.

Historian Cameron Hazlehurst describes how Winter watched the second circuit as the aircraft approached from the east then turned about 100 degrees to the left, losing height rapidly before disappearing behind the hills. ‘The aircraft flicked down and the port (left) wing continued to drop at an angle of 45 degrees,’ Winter said.

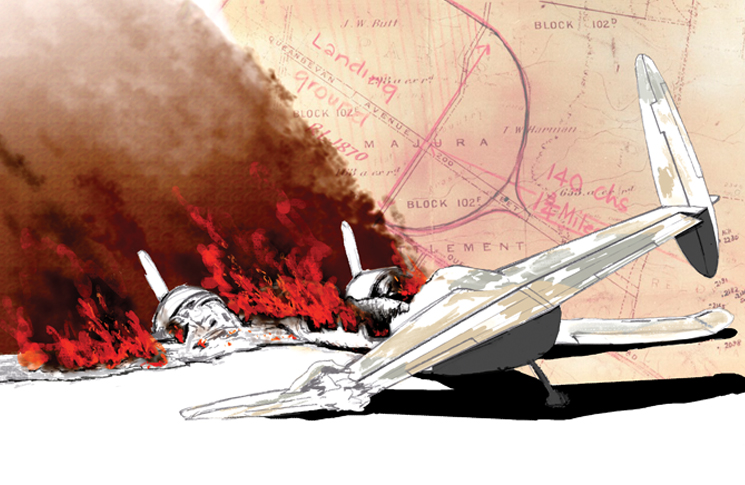

The Hudson crashed into the top of the ridge between Canberra Airport and Queanbeyan. The Air Court of Inquiry into the accident found that it was most likely the Hudson had stalled on landing approach, resulting in loss of control at a height too low to recover. The court found the crash had killed all occupants instantly, before a fierce fuel-fed fire destroyed most of the aircraft. The proximity of the crash to the RAAF base had enabled emergency crews to be at the scene within minutes, but nothing could be done to save the occupants.

Confusion and error definitely entered the story here, according to Andrew Tink, former NSW state politician and the author of Air disaster Canberra: the plane crash that destroyed a government. ‘There were egregious mistakes, which made it impossible to positively identify who was where in the fuselage,’ he says.

One of the main themes to emerge from the 680 pages of Hazlehurst’s monumental study, Ten journeys to Cameron’s farm, is confusion. Some witnesses described smoke and flames as the aircraft fell, others saw no signs of fire. The Hudson fell flat, nose down or inverted, depending on who was describing the scene. There were varying accounts of the position of the bodies and whether they had been killed by impact or flames. Aircraft accident investigation was undeveloped in 1940 but four separate inquiries were held into the crash: a RAAF accident inquiry, a RAAF court of inquiry, a Department of Air court of inquiry and a coronial inquest.

After all these inquiries had concluded, the RAAF was left with a few broad and bland phrases but little certainty on what had caused the aircraft to crash and little insight into how to stop such crashes from happening again. The RAAF court of inquiry found, ‘The accident was due to an error of judgement on the part of the pilot’.

Two unofficial theories became aviation folklore: that the handling pilot had not been RAAF Flight Lieutenant Robert Hitchcock but a passenger, the Air Minister James Fairbairn; and that Hitchcock, the son of a pioneering aviator who had enjoyed high-level patronage to enter the RAAF, had been a substandard and dangerous pilot.

What went down

Aircraft

With its streamlining, metal construction, constant-speed propellers and retractable gear, the Lockheed 14 and its military version the Hudson were very different to the slower, simpler biplanes of the 1920s and 30s.

The speed and complexity of these aircraft could seem unforgiving to pilots who had learnt in earlier simpler and slower cockpits. A 1939 issue of The Aeroplane described the Lockheed 14 as ‘delicate to handle … stalls suddenly, at a rather high speed, and so ought only to be committed to the care of thoroughly competent pilots. It is not a machine for the careless or the ham fisted.’

The RAAF Air Board had been concerned enough to issue a bulletin on the dangers of flying new aircraft as though they were older types:

‘The introduction of modern high wing-loaded, flapped monoplanes has rendered the old accepted methods of approaching and landing both difficult and unnecessary. Steep gliding turns with engine throttled back at low altitudes in the modern high wing-loaded monoplanes are necessarily difficult with more than a little danger involved in their performance, due to the rapid increase of the wing-loading to danger point resulting from a change of direction of the aircraft at comparatively low speeds.’

It is sobering to note that surviving aircraft from the 1930s and 40s continue to stall and crash with little warning, even when flown by experienced crews. The 2017 crash of a Grumman G-73 Mallard flying boat in Perth and the 2018 destruction of a Junkers 52-3m in Switzerland are sad examples.

Crew

The pilot Robert Hitchcock was, unusually for the time, a second-generation aviator. His father, a mechanic, had died of thirst in the Tanami Desert in 1929, after a forced landing during a search for Charles Kingsford-Smith. Hitchcock junior had joined the RAAF and had been mentored from the highest ranks.

Early in his flying career there had been some unflattering assessments of the younger Hitchcock’s piloting, but Hazlehurst interprets these in the context of a modest and quietly spoken young man from a humble background adjusting to the privileged and socially stratified peacetime air force.

Later assessments describe him as ‘a very sound pilot’ having ‘above average’ flying ability and being ‘definitely a cautious type’.

‘Hitchcock was one of the small group to be selected as the first to fly the Hudson,’ Hazlehurst says. ‘He’s a flight commander and training others. He did early test flying on the Wirraway. They didn’t give jobs like that to pilots with bad records.’

Both Tink and Hazlehurst note how Group Captain George Jones, later Chief of the Air Staff, gave a written reaction to the RAAF court of inquiry, saying, ‘I cannot believe that a pilot of Hitchcock’s experience would stall the aircraft under the circumstances which apparently existed.’

The second pilot on this flight was Dick Wiesener, who was there as part of his training. Wiesener, a licensed private pilot, was not yet qualified to fly the Hudson, meaning that in effect this was a single pilot operation.

Passenger: yes, minister?

James Fairbairn was the minister for both military and civil aviation. He had been a pilot in the British Royal Flying Corps during World War I and still flew as one of the country’s few

private pilots.

Rumours that Fairbairn had been in the pilot’s seat began early and persisted. ‘The stories gathered momentum over the years, mostly quietly and underground,’ Hazlehurst says. ‘What you discover is that there’s no doubt that the RAAF did its best to deflect attention from the possibility, of which they were very aware, that the minister might have been flying the plane. This was also a belief in [Prime Minister] Menzies’ office, which helps to explain the determination at the highest levels to ensure the story didn’t gain traction.

‘The RAAF’s default position was there was no evidence of engine failure or structural damage, there couldn’t have been anyone else flying the plane and therefore it must have been an error that Hitchcock made.’

Fairbairn had mentioned to Herbert Storey, an Adelaide trade school headmaster, how he was looking forward to experiencing the flight characteristics of the Lockheed Hudson firsthand: ‘On every possible occasion I’ll practise landings and find out more about this stalling trick’. Hazlehurst discovered the worried Storey had written a letter to the government after the crash.

Tink says Fairbairn’s words, as quoted in the headmaster’s letter, are ‘as strong a statement of intent as I’ve ever seen.’ On balance, he thinks Fairbairn was flying. ‘There’s enough of the lawyer left in me to know I have to follow the evidence,’ he says.

Hazlehurst is not convinced Fairbairn was flying, but says he need not have been at the controls to contribute to the crash. The notion of the sterile cockpit, with no extraneous conversation at low level, was probably ignored, he suspects.

‘My conclusion, explained at length in my book, was that it was more than likely Fairbairn was in the right seat, next to Hitchcock and chattering away, wanting to have things explained and distracting the pilot,’ Hazlehurst says.

‘The testimony of the firemen at the scene was that there were three bodies in the nose of the aircraft. The only way that could have happened is if the second pilot had been sent to the bomb-aimer’s position to make way for Fairbairn’.

But Tink says the Hudson’s dual control conversion which blocked access to the nose, would have made this impossible. Fairbairn would have to swap seats with Wiesener instead.

Hazlehurst says Fairbairn’s injuries from being shot down over the Western Front made him physically incapable of handling the controls of the Hudson. ‘Which is not to say he wasn’t fascinated to know what was happening. We know he was.’

However, Tink says Hudsons were more complex but not heavy to fly. The type was routinely flown during the war by slightly built women delivering aircraft for the Air Transport Auxiliary, he notes.

But on the issue of cockpit gradient—the gap in power and influence between two people on the flight deck—Tink and Hazlehurst concur.

‘Hitchcock was a working-class guy,’ Hazlehurst says. ‘He’s never been comfortable in the mess. He’s a member of the Church of Christ and a teetotaller. He’s never going to be at ease with a Western District toff like Fairbairn and he’s not going to send him back to his seat.’

‘You couldn’t imagine a steeper cockpit gradient than between Fairbairn, a war hero revered by pilots, and Hitchcock, a solid, unspectacular pilot from a humble background,’ Tink says.

The wider context

Every accident, no matter how minor, is a failure of the organisation,

Jerome F. Lederer, 1902–2004

Hazlehurst says the RAAF had not come to terms with the new technology of its growing fleet by 1940.

‘In the service environment all the senior guys knew each other very well, many were Great War veterans, it was a chummy, establishment environment,’ he says. ‘What they know and think is very different from what is required to transform the service during war and grow it at an enormously rapid rate, training people to fly a new generation of aircraft of which the senior commanders had limited understanding.’

The immense effort of creating what would be by 1945 the world’s fourth largest air force was straining training and ultimately safety. But the RAAF was blaming individuals. An air commodore wrote a terse minute in 1940 saying, ‘Unless Hudson squadrons are given better material from which to train captains, the accident rate will increase out of all proportion.’

Conclusions: the fog of war

Only a flight data recorder and a cockpit voice recorder, both science fiction technology in 1940, could tell us precisely what happened above that low hill on the outskirts of Canberra. But modern analysis can suggest why it might have happened.

Rapid growth in the RAAF had produced a situation where the senior ranks, including the minister, had little exposure to the realities of operating a new generation of aircraft. This may have combined with a cockpit gradient steepened by the nature of 1930s society and the clubbish pre-war RAAF. In fact, there were two gradients—between Fairbairn and Hitchcock, and between Hitchcock and his unqualified second pilot, Wiesener. Whoever was flying, this was an organisational accident.

Comments are closed.