By John Void

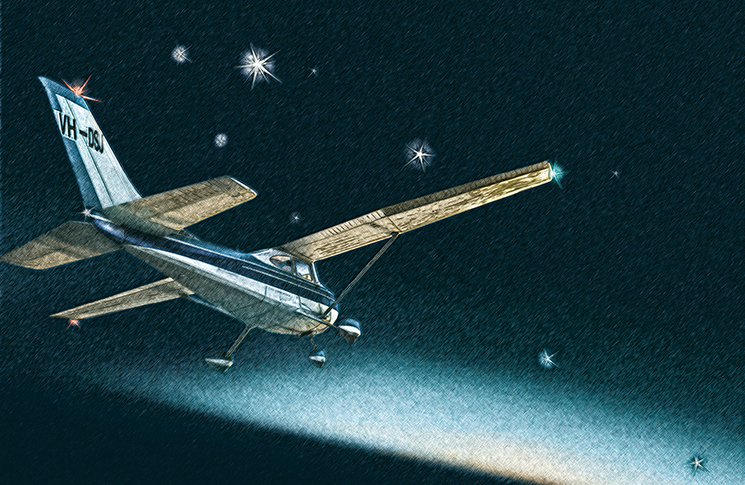

Becoming lost in unexpected bad weather and low on fuel was a scary experience.

For years, we had been flying around western Queensland to properties servicing fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters for stations. We flew often and knew the country well.

This particular week late in summer had been a long one, with stinking hot weather. We had completed our work and so, Friday afternoon about 4 pm, I decided I would fly home that evening instead of waiting until the morning.

Home was St George, 155 nm almost due east of Cunnamulla, which meant about an hour and 20 minutes in my Cessna. I packed up my tools and phoned home to the hangar to check on the weather. They confirmed the weather was the same in St George—broken cumulus at around 8000 feet. I estimated there was about two hours of fuel left in the aircraft and that was confirmed during the pre-flight. I could have refuelled if necessary, but I knew that the 30 minutes or so needed would have prevented me from getting away and arriving home before last light.

I rationalised that two hours minus one hour and 20 minutes’ flight time left me with about 40 minutes reserve, which I knew was respectable. And I knew the highway that connected Cunnamulla to St George was unmistakable—it was virtually a straight line that could be seen for about 30 miles. This alleviated my concern that my GPS was in another aircraft, so was not usable for my flight home.

I waved goodbye to my colleague who would be ferrying an aircraft home in the morning and left Cunnamulla at 5:15 pm local time. I climbed out to 7500 feet, leaned and trimmed the aircraft and, like so many other times during the en route phase of flight, tuned out. It felt good to know I would be in the St George local pub in about two hours sharing a few cheeky ones with my mates.

About 20 minutes into the flight, my attention was drawn to a fairly nasty-looking cell directly ahead, with accompanying rain. To go around it would require too many extra track miles, as well as leaving the main navigational cue of the highway, so I chose to descend immediately to get beneath it.

Over the years with my type of work (aircraft maintenance engineering), I had encountered a lot of bad weather en route to jobs, so choosing to fly through the rain ahead was of absolutely no concern. At 1000 feet AGL I levelled out underneath the cell and was hit by a wall of rain and darkness. I couldn’t believe how dark it had suddenly become. I even turned on the cockpit interior lights—they made a noticeable difference.

I checked the time. I had been flying for about 35 minutes, which meant about another 50 minutes to go. After about 15 minutes of almost IFR conditions, I flew out the other side of the shower. It was about 6 pm.

I scanned the horizon to assess the weather, glad to be out of that last shower and discovered that mostly overcast drizzly conditions were ahead for as far as I could see.

I had 30 minutes to go, so I looked again for the highway to align the nose and begin to relax again. The highway was nowhere to be seen.

I looked left and right, straining through the weather to find my only navigational cue but, for the life of me, I couldn’t find it. I grew very concerned, very fast. I calculated I must be about 60 nm from St George and grabbed my WAC. I drew a rough arc 60 nm from St George and looked for something familiar. The problem was the geography was so sparse that the only thing worth looking for was in fact the highway, which was proving impossible to find.

I decided I would track north by about 30 degrees for 10 minutes to see if I could locate it. If I couldn’t see it then, I would track south by 60 degrees for another 10 minutes or so. By then I thought I might be able to at least see some lights of St George, even if I couldn’t find the highway.

This plan yielded nothing, except becoming even more uncertain of my location. Was I north or south of the highway? If only I knew. I struggled with the reality that I was in serious trouble. I had been airborne for 70 minutes, which meant I should be very close to St George, but I couldn’t find it anywhere. What was worse—I only had 50 minutes or so of fuel left, it was getting very dark and the weather was terrible.

My ADF proved useless, as it just wandered around the dial aimlessly when I tuned in St George, so I attributed that to the storms around and turned it off. I used my UHF to call the hangar at St George and was glad to hear a familiar voice respond, even though they said it was ‘pissing down’. I called another of our remote strips and they confirmed that I could get in there. The problem with that was they were in Dirranbandi, which I knew must have been about 40 miles away—there was no margin for error in finding it, with my fuel status the way it was.

It was now 6.30 pm and I needed to make some decisions about the future of this flight. I ran the numbers once again, trying to find why I was in this situation. I thought I must have had the wrong times or that under the stress of the situation I had miscalculated how far I should be from St George.

The numbers worked out the same no matter how I ran them and now, an hour and 20 minutes since departure, with no destination in sight, I was in dire trouble. I fought tremendously hard against the desire to wander around looking for home and stuck to the track that was Cunnamulla to St George and monitored time. I knew that even though I was lost, that would only add to the problem.

I realised that I could actually fly past St George any minute now, which would change my search angle from 180 degrees in front, to a full 360 degrees. With only 40 minutes of fuel left and darkness approaching, that wasn’t going to work so, unbelievably, I began to look for a paddock to land.

I was already at about 1000 feet AGL and quickly chose my landing site. I did a fly past to assess it, flew a very tight circuit and landed uneventfully.

My heart was pounding and it was an amazing feeling to be on the ground, safe for the moment at least. About five minutes later, a man turned up in a ute to see what was going on. I introduced myself and told him I was hopelessly lost and short on fuel. I produced a chart and asked him if he could point to where we were, but he couldn’t decipher the map. I started reading station names, hoping he might recognise one, and sure enough, he did. ‘Oh, they’re my neighbours,’ he said. He pointed to where their property was and I was able to confirm that St George was about 25 miles still to the north/north-east. All this took about 10 minutes, so I thanked him for his help and said I needed to get going ASAP.

I worked out I was about 15 minutes from St George and had 30 minutes of fuel. All sorts of things went through my mind now, such as, ‘What If I can’t find it? I’ll have to make another forced landing and I might not be so lucky next time. It’s very dark and still raining. What if the weather gets worse closer to St George and I can’t get in there—what then?’

As if the decision to depart had occurred subconsciously, the engine roared as I advanced the throttle for departure. Being so light, with almost no fuel and only me onboard, the aircraft was eager to launch me into the bad weather ahead. I turned onto my heading, throttled way back to conserve some fuel and flew at the base of the cloud, which gave me just under 1000 feet AGL. The constant drizzle was preventing me from seeing St George, until I noticed the streetlights about five miles ahead.

I activated the PAL and located the runway soon after. I cannot explain the wonderful feeling that was.

I joined the circuit amid a very heavy passing scud, but I was so happy to have found the aerodrome that it didn’t bother me one bit. The landing was remarkably good considering my nerves and I let the aircraft run the whole length of the runway to stop.

I taxied slowly back to the hangar and was greeted by the same guy I had spoken to on the UHF about 30 minutes earlier. He walked out the front and said, ‘What the hell are you doing flying around in this soup?’ ‘I have no idea,’ I replied.

The next day I filled the tanks to see how much fuel I had remaining—less than 15 minutes. I had flown south of track when I was under the initial storm and lost sight of the highway.

My venture north didn’t locate the highway, presumably because of the poor visibility and then I flew south, further away from my initial track. Despite all this, I believe my navigational training saved me on that day, as I was able to use time well and not fly around aimlessly hoping to find my destination.

My tracks 30 degrees north and 60 degrees south were methodical and when I knew I had flown long enough to arrive had I not been lost, I was able to make the difficult decision to make a forced landing.

Thinking back on what I could have done differently under the circumstances, I can’t think of much to improve on. The weather was reportedly good, I had a good reserve and was going to arrive before last light. Turning back to Cunnamulla when I saw the storm may have been a good thing to do in retrospect, but at the time of assessing the storm, I had no reason to think it wasn’t isolated, because of the good conditions reported at St George.

Was I suffering from the well-known condition of ‘press-on-itis’? Yes, definitely, but I didn’t consider the decision to leave Cunnamulla a risky one.

I am fortunate to have got away with my life and aircraft intact after this flight. Had I not landed in the paddock when I did, I am certain I would not have found St George on my own and would have run out of fuel trying to find it. Who could tell what the outcome would have been then?

A happy ending from what could have been, due to a series of cascading events. It started with trying to beat last light and not refuelling because of time needed. That right there should have been the decider to not fly that afternoon. Better to be still alive next morning rather than possibly dead that evening.

“Can’t think of much to improve on”?!

Clearly the writer has more experience than I do; and knows the area and the weather well. But even as a relative newbie, I know that:

1. Flying VFR into IMC is asking for trouble (it sure doesn’t sounds as though either his flight or his aircraft was IFR).

2. The weather now is not necessarily what the weather will be in 30 mins time or 50nm away. Sure, he ‘phoned to see what the current weather was at destination; but there’s no indication that he looked for a forecast, and clearly the destination weather was very different by the time he arrived.

3. Fuel on the ground is useless. I don’t ALWAYS take off with full tanks; but if there’s weather about, or it’s late in the day, I surely will. What if the St George PAL had been out of action?

Good story, though. I take my hat off to the writer for his good sense and airmanship for landing in the paddock; but I put it back on again when I read that despite all his “what if’s” in the paddock, he still decided to take off again!

I don’t know if this is made up story but couple of things are not clear. 1st flying into clouds for 15mins – no comments here. 2nd lost procedure is not the same I learnt in my school, but probably makes more sense in remote flat Queensland bushland. 3rd departing again after emergency landing with low fuel – beyond my comprehension !!.. Finally, I’m checking Ersa says Brisbane FIA 118.95 is available >on the ground< at YSGE, meaning it is available even further when above the ground. A simple call asking for help, then a squawk later would help pilot to arrive home much earlier and safer. Nothing to be embarassed, ashamed or whatever. ATC is here to help. Cheers from low ~90hrs private pilot.

SK : Very good post above,even though only a 90 hour Private pilot. A lot of grief could have been saved if the aircraft had have been ADSB fitted. ATC could have assisted him a lot better in that situation.They are there to help use them .

Having flown/driven that area many times, it is flat and rain puddles(lakes ) would confuse any vfr pilot . But, it is due east of Cunnamulla, on the intersection of the Balonne Highway, Castlereigh Highway, Carnarvon highway,and the Moonie Highway and the Balonne River, with Lake Kajarabee just a few miles North, so just basic navigation, fly your heading-East in this case and use your clock, ie basic dead reckoning would have got you in the ball park to a very major crossroad in south Queensland, plus you would have crossed the major North/South Carnarvon Highway, which, you could have landed on in an emergency. I am not trying to be a smart arse, just for the benefit of others, Dead reckoning worked for old navigators hundreds of years ago and is a good excersize to practice when things go pear shaped, be it flying, hiking, 4wding, boating, when your GPS and ADF fail.

Very good responses from the various low-time pilots in the comments above! I was surprised that the pilot in the story seemed to be very familiar with the territory he was flying over and apart from the very dangerous decision he took early in the flight to fly through the extremely heavy rain storm, I don’t understand why he would not have made sure of his track using his DG and compass to ensure he didn’t stray off track, while he was virtually flying in IFR conditions in the heavy rain??

I can cincur with all of the comments above as regards his decision to depart without fuelling & into oncoming dusk.

There is the stsrt of the chain straightaway.

Then to continue in the manner he did,sheer stupidity.

This pilot was what you aussies term a wombat.

No way would i have done things like that

I know it’s always easy to say what we would have, could have, should have done in hindsight from the comfort of our lounge chair, but for me, this was a good example of bush flying where an unexpected weather situation forced a pilot to think things through, under stress, and lived to tell the tale. I agree with some of the comments, but again in hindsight, who of us perform perfectly under stress, Let’s all simply learn from this honest and open article and avoid putting ourselves in a similar situation?

I was just looking at the terrain from Cunnamulla to st.george forced landing with power and fuel looks so easy witch it really is… put panic with fuel starvation in the pic different ball game he should never have took off the 2nd time…

Really hope he got the ride!!