By Robert Wilson

The enduring lesson from this 90-year-old tragedy is most unsettling

‘O you who turn the wheel and look to windward,

Consider Phlebas, who was once handsome and tall as you.’

TS Eliot, The Waste Land, 1922

…..

Australian National Airways

Avro 618 Ten, Southern Cloud

Toolong Range, Snowy Mountains, NSW

Saturday 21 March 1931

…..

They just disappeared. The passengers and crew of a near-new airliner, gone, despite its reassuring redundancies and advanced design. All searches were futile. But the year is not 2014, and the flight is not MH 370. It’s 1931 and the flight is not even numbered because commercial aviation is so new. Instead the disaster has come to be known by the name of the aircraft involved: Southern Cloud. The first airliner to disappear on a scheduled flight, it remained missing for 27 years seven months and five days.

The Southern Cloud was one of five Avro Ten aircraft operated by Australian National Airways, the airline founded by pioneering aviators Charles Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm. The Avro Ten was a British-made licensed version of the Fokker FVII.3m that Kingsford Smith and Ulm had flown across the Pacific Ocean in 1928. On 21 March 1931 it took off from Mascot Aerodrome for the daily service to Melbourne. It was heard over Goulburn in NSW, but never definitively seen again.

Looking at the wood, tube and cloth of the Southern Cloud and its open-sided flight deck, it’s easy to be condescending about the safety standards of its era – but wrong. Australian National Airways was, by the standards of the time, a well-run airline that prioritised safety.

In his introduction to renowned aviation writer Macarthur Job’s definitive work on the tragedy, Into Oblivion, Ulm’s son John writes of how his father ‘strode easily in corporate corridors’, how Qantas chairman Fergus McMaster had noted Ulm’s acumen and Qantas founder Hudson Fysh lamented having such a formidable rival. Among Ulm’s initiatives was investigating three European start-ups: Imperial Airways, KLM and Lufthansa. ANA’s engineers had been sent to England for training by aircraft maker Avro and engine maker Armstrong Siddeley and the airline had strict inspection, maintenance and overhaul schedules.

That Saturday has another place in history. As of 2020, it remains the coldest March day recorded in Melbourne. The temperature climbed to 12 degrees, but strong westerly winds and driving rain made it seem colder. The weather in Sydney was more moderate; Ulm told the official inquiry held the following month he had been sailing that afternoon. ‘I would not have called it a particularly bad day by any means,’ he said.

ANA’s Melbourne pilots had no such illusions about the suitability of the day for flying. ‘Scotty’ Allan, who flew the Melbourne-Sydney service, described going straight into what we would now call instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) and not seeing the ground again until Holbrook in NSW. He told the inquiry of winds ‘of such an intensity and over such an area that has never been encountered before between Sydney and Melbourne’, and described how he had to crab the aircraft at an angle varying between 45 and 55 degrees, to maintain a semblance of planned track. He estimated the wind at up to 100 mph (88 kt).

Jim Mollison, flying the service from Melbourne to Launceston, said, ‘weather conditions were exceptionally bad, probably the worst visual conditions I have yet experienced’.

Yet both took off. One reason for their confidence was ANA’s wholehearted adoption of the then new and controversial doctrine of instrument flight. The airline’s pilots had been taught the American needle-ball-airspeed method of low-visibility flight control by Kingsford Smith personally. He had learnt this method in preparation for his Pacific flight from its inventor, the courageous and persecuted William C Ocker of the US Army Air Corps. Needle-ball-airspeed involved scanning the gyroscopic turn indicator, balance ball and airspeed indicator. The technique had helped Kingsford Smith to fly safely through the storms of the Pacific’s intertropical convergence zone in what to any modern pilot must seem a superhuman feat—hand flying by partial panel for hours on end. As a commitment to the method, ANA’s fleet had been fitted with state-of-the-art turn indicators, improved compasses and a redundant instrument lighting system using dual batteries.

That day’s pilot of Southern Cloud, Travis Shortridge, was an able practitioner of this new art. Macarthur Job, author and former editor of Aviation Safety Digest, rediscovered a piece Shortridge had written for Slipstream magazine in 1930 and was impressed by what he read. ‘Any experienced pilot reading Shortridge’s advice on “blind flying” will recognise he knew what he was talking about,’ Job writes. Among Shortridge’s maxims were, ‘It is wiser to fly 20 miles in the opposite direction to gain height over flat country than to gain it on course over rising country’ and ‘don’t dive through the first hole you see [in cloud] – it may be on the edge of a hill which remains obscured.’

A graduate of Britain’s Royal Military College, Sandhurst and former Royal Air Force pilot, he was regarded as a safe and expert captain by the more individualistic standards of the time. These were somewhat different to standards in the modern era of flight data analysis. A contemporary, Raymond Garret, (later a distinguished RAAF officer) remembered Shortridge making a series of stall turns during landing approach on a passenger flight in the Avro. ‘Then he pulled out, straightened up and with a grin from ear to ear made a perfect landing,’ Garret wrote in 1981.

ANA’s flight planning was more reassuring. The company had an established relationship with the Sydney Weather Bureau, which delivered a forecast at 10.30 am six days a week. For flights leaving earlier, pilots consulted that day’s Sydney Morning Herald weather map, which was compiled the previous evening from the day’s observations around Australia. Shortridge would have done this before taking off at 8.15 am. At 10.30 am, the Victorian 9 am weather observations for Saturday reached the Sydney bureau and alarmed the duty meteorologist enough for him to call ANA’s office and speak to Ulm. It was too late. The Southern Cloud had no radio and could not be reached.

Here, there and everywhere

Over the following days a pandemic of what modern psychologists would call confirmation bias swept across Australia, as sightings of the aircraft poured in. There were 383 reports of Southern Cloud, some with lurid details such as notes with panicked messages being dropped from the aircraft.

These placed the aircraft anywhere from the Bellarine Peninsula near Geelong, to Bathurst, just as in the following century people reported MH 370 in Cambodia, Vietnam, Mauritius and Central Asia.

Kingsford Smith told newspapers he believed the aircraft was in Bass Strait and the controller of civil aviation, Horace Brinsmead, told the inquiry, ‘To my mind the evidence is almost overwhelming that the pilot did get over the sea and that the accident took place between that point and reaching Point Cook.’

The airline’s pilots had been taught the American needle-ball-airspeed method of low-visibility flight control by Kingsford Smith personally.

The observant walker

On a Sunday late in October 1958, carpenter Tom Sonter took a break from working seven days a week on the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme. Leaving the work camp at 7.30 am, his plan was to climb a nearby mountain called Black Jack, take photos and be back for lunch. By 9 am he realised he wasn’t going to make it. Rather than retracing his steps he took a scenic route back, traversing a steep wooded slope.

He saw ‘a piece of steel poking through the saplings up the slope from the mound’ and interpreted it as an abandoned mineshaft. ‘I walked over to have a look, and absent-mindedly put my hand on the steel. There was no hole (in the ground) so I gave up on the idea of a mine – and I looked up. Where my hand was, I could easily see was the tail of an aeroplane.’

Quick and the dead

Macarthur Job’s writing did not as a rule contain villains. His meticulous analysis of aircraft crashes focused instead on factors and frames of mind. But a villain emerges strongly from the pages of Into Oblivion – the then director of air safety investigation, the late C A J Lum, a civil servant whom Job describes as ‘highly competent but pedantic and aloof’. Lum saw no reason to order a full investigation of such an ancient crash and sent investigator AH Green to do no more than confirm the wreckage was indeed Southern Cloud. ‘In so doing he denied the nation for all time a deserved answer to so perplexing a mystery and allowed the desecration of a grave site,’ Job writes with radiant anger.

Lum’s unimaginative decision was one reason we have little certainty about what happened to Southern Cloud. The other reason is a rather silly film loosely based on the story of the crash – Secret of the skies – a 1934 melodrama that embellished the story with a bank robber on the run, gold bullion and romance between a dashing purser and a passenger. When word of Sonter’s discovery got out, the half-remembered prospect of jewels, cash or gold propelled a horde of Snowy workers to the crash site, where they scavenged and souvenired at will. ‘Our museum is still receiving fragments of the Southern Cloud more than 60 years after the discovery,’ Tumbarumba Historical Society president Ron Frew says. ‘They come from all over Australia.’

In the face of official indifference and disorder at the scene, Green did a good job, far exceeding his cursory brief. He was able to establish that Southern Cloud had struck the ground facing north-east – the reciprocal of its Sydney-Melbourne flight path. No trace of the wing structure was found, except for aileron hinges which, along with the relative positions of the engines, suggested the aircraft had been in a steep right bank. A watch found in the wreckage was stopped at 1.15 pm.

Both ANA and NASA thought they were managing the hazards successfully.

A 1963 book postulated Southern Cloud had flown as far as the flatlands of central Victoria before being blown east when, for unexplained reasons, it climbed again. The watch, and Shortridge’s written warning against flying towards rising ground strongly contradict this.

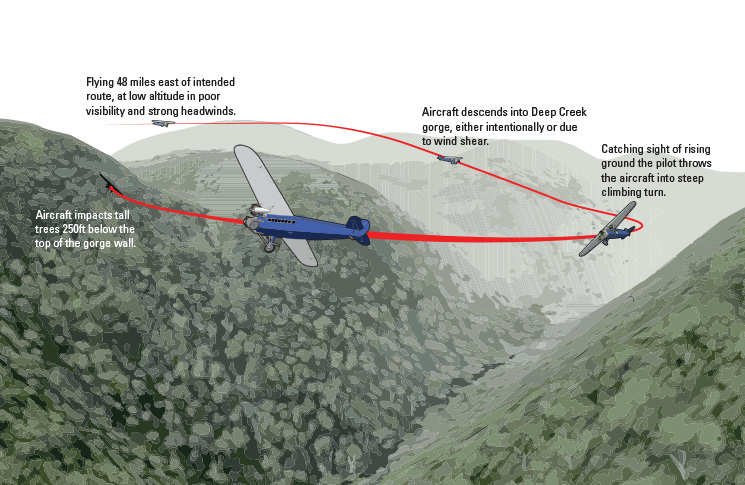

Shortridge’s recorded expertise in instrument flying adds weight to the theory the crash was a controlled flight into terrain (CFIT). After nearly five hours in turbulent, freezing IMC, Shortridge and his 400-hour co-pilot, Charles Dunell, would have descended, not realising the headwind meant they were still over mountains. The aircraft probably flew west into Deep Creek gorge and was forced to turn when Shortridge saw steep terrain ahead. A south-westerly wind would have stretched the ground track of this turn and blown the aircraft into the northern ridge.

On the balance of probabilities this is what most likely happened, but other endings cannot be altogether discounted in view of the unexamined evidence on the ground. The role of localised mountain leeside turbulence in the crash is a wild card in this scenario, for example. A spin or spiral dive in IMC cannot be definitively ruled out, nor can aircraft break-up in flight, because this happened 10 days later. On 31 March 1931, a Fokker F-10 broke up over Kansas, USA, killing eight people and spurring the rejection of wooden wing aircraft by the US public and government. The investigation found moisture had weakened the Fokker’s main spar.

Green wrote the aircraft had caught fire on impact, but Job disagrees. At least two bushfires passed through the area before the wreckage was found and these could account for the disappearance of the wing and the melting of aluminium. The engines, however, were unburnt, which Job says suggests that the fire that destroyed the wreckage occurred later, after they had been buried by the impact and under plant litter.

No fire, or merely a flash fire, raises the possibility of survivors. Job interprets the wreckage as indicating the aircraft struck tall trees which grew on the slope at that time. The massive wooden wing would have absorbed some of the impact, he argues, saying it is possible that passengers on the left side of the cabin might have survived this sequence. Because there was no analysis of human remains at the site we do not know if all on board can be accounted for. And another item found at the scene raises this disturbing possibility. In the Airways Museum at Essendon, Victoria is the remains of a camera, found at the crash site. It is not mentioned in the text of the 1958 report, only in the wreckage position diagram where it is recorded as being downhill and behind the aircraft. ‘It is difficult to conceive how the camera lens could have reached this position if not placed there by human hands,’ Job writes.

There were survivors from a similar crash. In February 1937 a Stinson airliner crashed in the border ranges of NSW. Three passengers survived, two of whom were found alive by a bushman acting on a hunch about where the aircraft might be.

‘It would be hard to imagine a more appalling predicament,’ Job writes. Frew concurs. ‘Imagine being injured, maybe burned, cold and alone in a steep and literally trackless wilderness.’ Job thinks Green did not wish to torment the victims’ families with the prospect of their loved ones dying a lonely and protracted death. He tracked down the retired inspector but Green died days before Job was to speak with him.

Our museum is still receiving fragments of the Southern Cloud more than 60 years after the discovery.

Meaning and remembrance

Was Lum right? Is nothing to be learnt from Southern Cloud?

Modern airline transport grapples, successfully, with a different set of safety issues. For general aviation, the lessons about weather and mountains are ongoing – and not always heeded.

In 1971, 40 years after the crash, Job editorialised in Aviation Safety Digest about how pilots were still having CFIT crashes. ‘All too many general aviation pilots are apparently willing to “give it a go” even when indications are all against safe completion of a flight,’ Job thundered.

There’s even less excuse for flying into terrain in the 21st century. Modern general aviation pilots have electronic flight bags, which would have seemed utterly miraculous in 1931. Yet CFIT crashes persist. ‘The pilot, who was qualified only to operate in visual meteorological conditions, flew toward and entered an area of low cloud and reduced visibility,’ the Australian Transport Safety Bureau said about the fatal crash of a Cessna 182 in April 2019. In September that year five people died when a Bell UH-1D Huey was flown into low visibility conditions.

Past performance does not guarantee future results.

There’s a broader philosophical lesson in Southern Cloud. Its loss is similar in general terms to the space shuttle disasters of 1986 and 2003. Launching a space shuttle is, of course, a much more complex system than flying a wood and fabric trimotor between cities, but both were at the technological and operational frontiers of their time. Each attempted to manage known hazards, while not comprehending the true dimensions of those hazards, and both ANA and NASA thought they were managing the hazards successfully, based on the fact that until the fatal day nobody had been hurt. (Until the crash, ANA had flown more than one million km without injuring a passenger.) Each successful flight or launch added to this illusion but, as investment prospectuses say, ‘past performance does not guarantee future results.’ The larger safety question is whether these sorts of crashes are ‘normal accidents’ – in the mournful phrase of sociologist Charles Perrow, who argued that some accidents were an inescapable consequence of complexity, in machines, systems and environments – or whether a failure-obsessed high-reliability organisation can sniff out and head off disasters before they occur.

Silence and insight

An overcast Friday late in October proved to be the perfect day to appreciate the fate of Southern Cloud. From a lookout south of Tumbarumba, rows of mountains gazed back, grey and sullen, as if unwilling to yield a single clue to their interrogator. In recent years there would have been contrails in the flight levels over the sacred and profaned ground of the crash site, but this was 2020. It was as though the sky itself was saying ‘You people are not as smart as you like to think you are, even now’ as rain began in earnest.

Thanks for a great story! Despite the obvious lessons for us mere GA pilots, what bothers me most is “the desecration of a grave site” and not returning what was left of passengers and crew to their families.

An excellent report written so well that this may partially dent the powerful messages it contains. After 43 years professional flying I know I must apply my rule of “Just because I can, does not mean I should”. As well, MUST GET THERE-Itus still traps the unthinking whon will not safely pause somewhere to let crap weather go away before continuing the flight.

In MacArthur Jobs story in airline crashesinAustralia he showed newspaper photos otowns in direct view of the high crash site with newspaper headlines reporting people in the towns reporting seeing lights where the crash occurred. Indeed there may have been survivors.John Tully

Hi John, thank you for your remarks.

On page 89 of Into Oblivion, Mac Job writes about visiting Tintaldra, where lights supposedly shone by survivors were said to have been seen, and coming away sceptical about whether this could have occurred as reported,because of the distance and compromised sight lines. ‘A more detailed consideration of the theory of the Tintaldra lights has inevitably led to a degree of scepticism about the reliability of the press reports,’ Job writes. This does not, of course, rule out the possibility of survivors.

The vision of the lights may have been part of the well-meaning hysteria that followed the crash. Reports from a station worker at Lambrigg, south of Canberra, and by gold prospectors near the Toolong range were probably accurate, but swamped by the volume of imagined and in some cases impossible sightings (given the aircraft’s range).

The accident investigators now know that the most reliable, though not 100% accurate, reporters of viewed events are boys of about 12 years. Adults reshape their narrative of events to have it make sense to them, and others let emotions and desires distort their reports.

As police investigating experience, more reports does not mean more useful information – just more work to wade through the confusion to find what is worthwhile.