A helicopter that pitched over on the roof of a skyscraper, killing 5 people, had been subject to stresses caused by the cost-cutting practice of keeping the rotors turning during passenger offload. What have we learnt since?

If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear as it is, infinite.

William Blake

Are we managing reality when we’re managing safety? Flight 972 of New York Airways in 1977 has some compelling lessons, especially about the power of a worldview.

Flight 972 was very similar and very different to other regular passenger transport (RPT) flights. It was very similar because it was one of 32 flights a day at cut-price ticketing ($50 or less) with two pilots, a cabin attendant, fare paying passengers and in-flight refreshments.

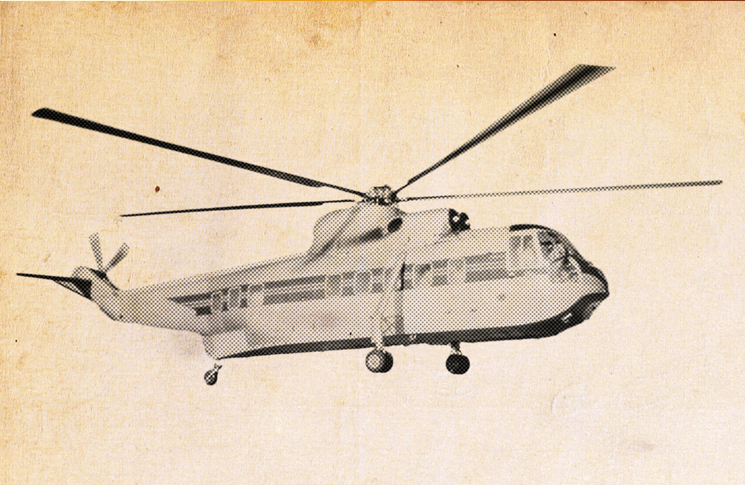

But Flight 972 was very different because it was a 28-seat S61L helicopter – a variant of what most in Australia know as the Sea King and its ‘airport’ was the 900-foot high top of the Pan Am skyscraper in the centre of Manhattan. This was the golden age of urban mobility where, for less than a peak-hour cab charge, one could commute from downtown New York to a connecting international flight in 10 minutes. The impressive spectacle of large helicopters operating from the heart of the Big Apple made it seem as though the future had arrived – Ridley Scott certainly thought so, seeing it as inspiration for Blade Runner.

Of course, not everyone shared the optimism of this futuristic worldview. Erik Stapper, a director of a representative community board in Manhattan, said: ‘It was sort of a fun idea [and] yeah, it’s futuristic. But I really did become scared something was going to happen.’

This contrasted to the worldview of New York Airways which regularly promoted the benefits of avoiding rush hour traffic snarls and ‘enjoying the thrill’ of zooming past the Statue of Liberty. ‘Scared something was going to happen’ was one narrative; another was the ‘convenience’ and the ‘thrill of the zoom’. Which one was right? Which one was wrong?

Those were the highly disputed multimillion dollar questions. Some might have wished for a simple answer but the more complex reality was both worldviews had measures of clarity and obscurity. There really was risk and there really were benefits, and both views needed to be combined to ‘cleanse the doors of perception’.

Preventable accidents such as that of Flight 972 are many things, but they are never less than the reckoning of the pre-accident worldview. We all have a worldview, that is, a narrative, a meaning-making story that streamlines and harmonises the aggregate of our motivations, fears, present knowledge, past knowledge and future imaginings.

Our worldview situates things into an all-embracing grid of ‘how things really are’. And here’s where things get tricky because a streamlined worldview is often more view than world, that is, a more simplistic perception of the world than the world as it really is. And when the complexity of reality is shelved for the convenience of simplicity, Blake has it right: the doors of perception are ‘uncleansed’. Such was the case with Flight 972.

It ended up being a maintenance cost that they did not want to deal with

‘The thinking was the cost … it ended up being a maintenance cost that they did not want to deal with.’ Pilot Jim Brundige was referring to the fact Flight 972 was kept ‘turning and burning’ on the Pan Am heliport during passenger offload.

A helicopter has numerous high-speed rotating parts, including bearings, seals, dampers, flap-stops and droop-stops, that experience significant wear during shutdown and startup. For Flight 972, turning and burning meant cost savings were placed over and above the relative safety of a shutdown for passenger transfers.

In this worldview the costs that felt the most real were not the extrapolated tragedies of an unrealised accident but the clear and present invoicing of a multizeroed purchase order. Of course this isn’t surprising – any glance at modern safety literature shows the ‘reality’ of ‘the cost right now’ often supersedes the reality of the perhaps, maybe, but not yet reality of an accident.

Until the accident happens

Landing gear on helicopters is like a leg: necessary, essential and taken for granted – until it breaks. The landing gear design on Flight 972 had a troubled history. The gear on another S61L, operated by Los Angeles Airways, had snapped while the aircraft was ‘turning and burning’ during a mail load at Los Angeles Airport (LAX). The aircraft rolled onto its side, seriously injuring one person and ejecting rotor debris into a nearby terminal building. The landing gear tubing was found to be fatigued and a determination made by the component manufacturer to increase – by 1 mm – the tubular construction and maintain overhaul scheduling at every 9900 hours.

It was determined the 1 mm of extra metal would prevent recurrence. It didn’t.

In 1977, 16 May was overcast with broken clouds at about 1500 feet, only 700 feet or so above the Pan Am heliport. Of approaches on such days – low cloud, low visibility and mechanical turbulence over the artificial mountains called skyscrapers – one experienced pilot said they were the most challenging since being shot at in Vietnam.

Unexpectedly, however, it wasn’t the weather conditions that would be emphasised in the accident investigation. It was that necessary, essential and taken-for-granted landing strut.

Sometime in the 7000-hour life of the right-hand strut, a surface pit had grown into a crack. With ongoing moisture ingression, short-cycle flights, multiple landings and ‘turn and burn’ passenger transfers, the crack had become dangerously long and the scene was now set for a sequel to the LAX crash.

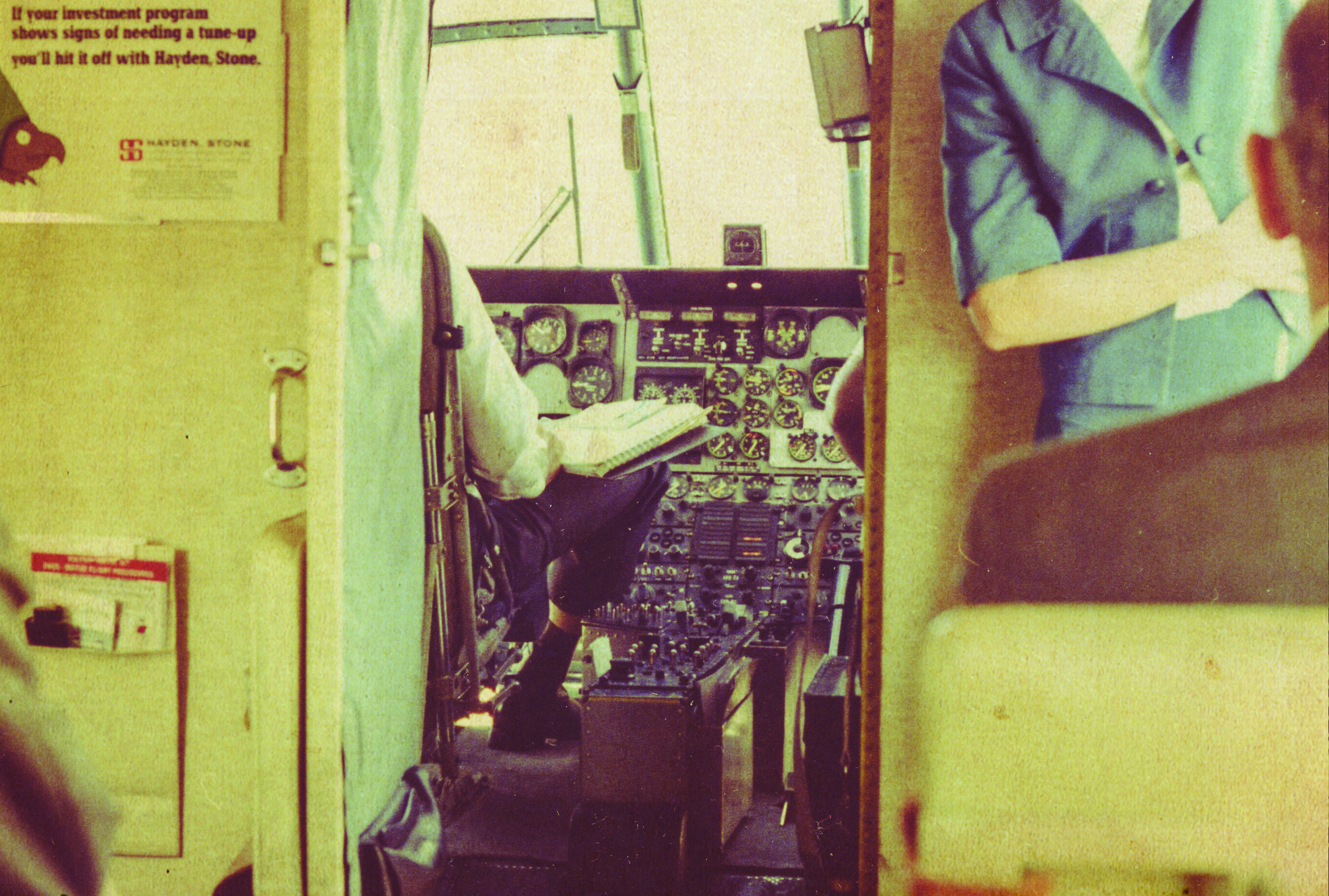

Despite the low cloud and fading light, Flight 972 landed safely in the late afternoon and began disembarking its 20 passengers. The captain had bottomed the pitch and the first officer stuck his left leg out to keep the collective at its minimum setting. Both were aware inadvertent power application, spinning rotors and disembarking passengers were a disastrous combination.

But while the pitch was successfully flattened, the rotor blades still spun at 100 per cent rpm which meant that, just above fluffed-up seventies’ hairstyles and fluttering pant suits, five 100-kg steel blades spun swiftly, with their respective tip speeds at just under 700 km/h. Ironically, by complying with the policy to keep running, the crew were about to demonstrate how to successfully comply with policy – all the way to the scene of the accident.

A faint but distinctly abnormal noise came from right and rear of the aircraft. Then a metallic crunching. Then a crumpling noise. Then a dramatic roll to the right. The crew members were surprisingly quick off the mark. The captain reached up for the engine controls but with the sudden collapse, no reflexes in the world were fast enough to shut down the engines and shove the rotor brake lever forward. One split second there was noise and the next the machine was on its side. The crack had propagated through 40 per cent of the strut, meaning the remaining metal could no longer support 8 tonnes of aircraft.

When the rotor blades slammed into the concrete, the precision-engineered aerofoils shattered into high-speed, jagged pieces of shrapnel. Four passengers were struck and died instantly. Such was the unrestrained energy of the shattered rotors, one blade fragment was later found

4 blocks away, while another flipped and turned its way down 23 stories, boomeranging its way back into the Pan Am building via a 36th floor window.

That wasn’t the worst of it. Another blade fragment, projected even further outwards and downwards, and still spinning, cleared a nearby hotel building and plunged onto the street, killing a young woman returning home from work.

In the aftermath, recommendations were made about inspection intervals, response plans and cockpit door design. Significantly, no recommendations involved the ‘turn and burn’ policy, nor were any significant judgments made about the use of CBD heliports.

It would be up to the lawyers to see the Pan Am heliport permanently close. The narrative of ‘convenient’, ‘fun’ and ‘futuristic’ went into insolvency, along with New York Airways, and the idea of urban air mobility slept quietly for decades, until resurrected in the last few years.

Which leads us back to worldviews

The multi-part narratives of cheap urban air mobility versus fear of an accident versus prestige of early adoption versus regulatory imperatives all bring various degrees of clarity and obscurity. Cleansing the doorway of perception must, at the very least, mean we genuinely understand, not delegitimise or understate, the voice of alternate narratives. This brings more world, less view; more reality, less perception.

And this is where things could get hopeful because being willing to modify and enhance our own worldviews, based on an openness to others, might cleanse our biases and purify our thinking and bring us all closer to a safe, innovative and flourishing operation, whatever that operation might be. It is in this way we can manage the laws of physics rather than the laws of perception. In this way we might actually accident proof, not merely litigation proof.

Which leads us back to our opening question: Are we managing reality when we manage safety? In the case of assessing ‘protection versus production’ over dense city centres so many decades ago and again more recently, if we’re not actively encouraging respectful but oppositional narratives, we’re only managing our own recirculated propaganda. So let’s listen to each other, especially when we disagree, so that our worldview might be a real view. That’s going to be important when proposals for urban rotorcraft trips to the airport reappear.

Further reading: Multi-engine helicopter operational performance standards directive at casa.gov.au