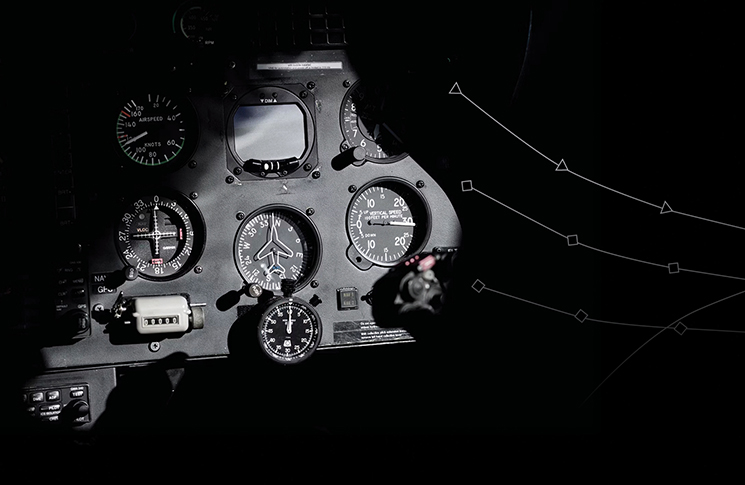

It vies with the wind-indicating tuft of wool for the title of simplest aircraft instrument, requires no power source and is always on standby. Ground or satellite systems may fail, but the magnetic compass is as reliable as the Earth’s magnetic field. However, to fulfill its promise of completely independent accuracy and reliability, a compass requires occasional skilled maintenance.

CASA has issued new guidance on checking and calibrating aircraft magnetic compasses. The airworthiness bulletin also provides information on the maximum allowable deviations to enable a compass to be maintained to its type design.

A compass is initially verified at manufacture to ensure it meets the relevant design standard and the indications are within the design tolerance. Once fitted to an aircraft, compasses are calibrated on a compass swing site (often a place on an aerodrome, with the cardinal points, north, south, east and west, marked on the ground) so corrections can be made for the magnetic fields produced within an aircraft. Compass calibration should be conducted at least every 2 years unless the aircraft’s approved maintenance program sets out a different period.

Compass calibration should also be checked at other times such as after an engine change, after electrical or avionics modifications, after a lightning strike, an accident or heavy landing, after long-term aircraft storage and whenever an aircraft is moved to a significantly different latitude.

CASA’s new Airworthiness Bulletin 34-008 Issue 3 includes preparations and procedures for checking and calibrating a compass, in a procedure known as a swing, and guidelines for when compasses that deviate from correct readings are to be compensated with correcting magnets.

In September 1987 I flew a new Mooney 231 from Jandakot WA to Parkes NSW. The weather was CAV OK until after Forrest and daylight until about the NSW border. The flight plan was IFR and our one refueling stop was Forrest. Compass alinement confirmations on take offs at Jandakot and Forrest were correct.

On the Forrest to Parkes leg we flew above cloud (can’t remember the Flight Level). Over the Nullarbor there was a break in the cloud and looking down all I could see was the ocean!!! A cleared decent to below the cloud continued to reveal ocean to the north until finally, clear of cloud, I could see the cliffs at the Head of the Bight some miles north. Hard turn to port! No angled track interception, needed back over land asap, that was great white territory down there!

It turns out the Mooney had had prop deicing fitted since I had last flown it and the compass had not been reset. On this flight the prop deicing had only been activated after Forrest.

I think the 2 year recalib is overkill, my Dynon EFIS once initially calibrated does not need 2 year rechecking. How often is the compass out more than a degree between checks ? With EFIS, EFB etc does it matter?

What does matter is the laborious power on compass rose check that takes ages and over heats the engine unless you are there to say ‘enough is enough’