The misunderstanding that led to a terrible accident also highlighted the need for proficiency in aviation English. Progress has been made but experts warn the task is far from finished.

It was, and remains, the world’s deadliest mid-air collision, and the third deadliest aviation accident.

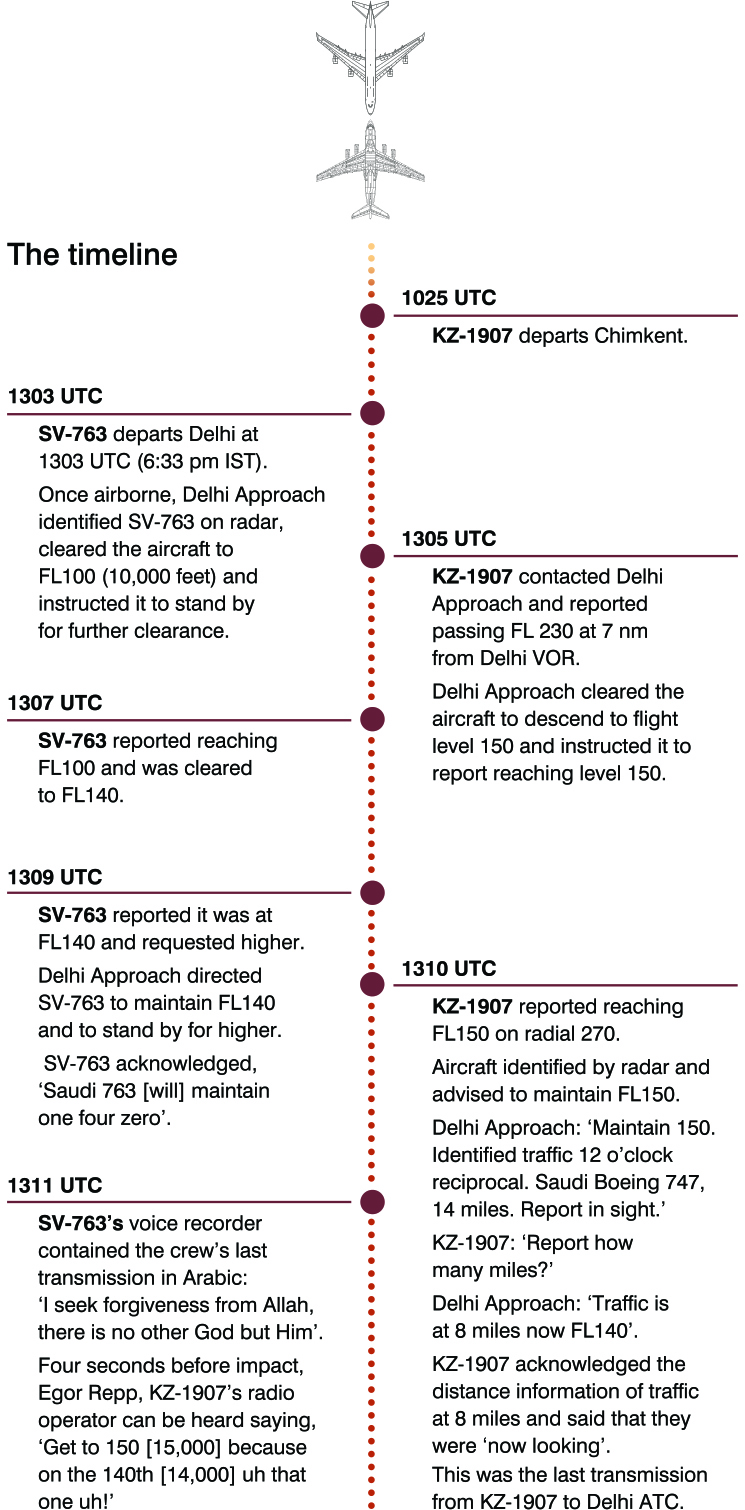

Just over 25 years ago, on 12 November 1996, Saudi Arabian Airlines (then Saudia) Flight 763 (SV-763), a B747-100, and Kazakhstan Airlines Flight 1907 (KZ-1907), an Ilyushin-76, collided over the Indian village of Charkhi Dadri, about 50 nm from Indira Gandhi International Airport, Delhi. All 349 onboard the 2 aircraft were killed, with victims suffering what the official inquiry report described in considered language as ‘multiple fractures and injuries suggestive of crash forces which were beyond survivable limits’.

Debris weighing 500 tonnes rained over the cotton and mustard fields below, spread over an area more than 7 kilometres long and 5 kilometres wide. At the time, a USAF C-141 cargo aircraft was flying from Islamabad to Delhi and had begun descent into Delhi terminal area. The pilot, Captain Timothy J Place, the sole eyewitness, told Delhi Approach, ‘We saw something to our right, looks like a big fireball in the cloud … I saw fire debris … 2 distinct fires on the ground’.

Saudi Arabian Airlines Flight 763 was on its regular tri-weekly schedule, the first leg of a service between Delhi and Jeddah, carrying Indian nationals to work in the Gulf, while Flight 1907 was a non-scheduled charter flight from Chimkent in the former Soviet republic of Kazakhstan, to Delhi.

Both aircraft were flown by experienced pilots, each with over 9,000 hours, including almost 1500 on type for the Kazakh captain, Alexander Cherepanov. However, Cherepanov’s English was uneven and the radio operator Egor Repp was translating for the pilots. VK Dutta, an experienced air traffic controller, was controlling both flights.

KZ-1907’s recorder documents their tragic final few seconds. Eighteen seconds before collision, continuing to descend, Cherepanov asks, ‘What level we were given?’. The flight engineer says, ‘Maintain’. Did they believe they were cleared to 14,000 feet? Repp, trying to restore the situation, says, ‘Keep the 150th [15,000 feet], don’t descend!’ At 11 seconds before impact, Cherepanov, possibly attempting to climb to FL150, asks the engineer to accelerate. Seven seconds later, Repp says, ‘Get to 150 [15,000] because on the 140th [14,000] uh that one uh!’

The official report of the Court of Inquiry, released in July 1997, was unequivocal in finding the cause of the disaster to be pilot error. ‘The root … cause of the collision was the unauthorised descending by the Kazak aircraft to FL-140 and failure to maintain the assigned FL-150.’

However, despite this unhelpful finding, the report did highlight numerous other contributing factors in its findings and recommendations. These included Delhi ATC’s obsolete primary radar which, unlike secondary surveillance radar, could not read transponder information on aircraft to identity altitude – SV-763 was transponder-equipped – merely distance and bearing. The airport also operated a single corridor for arrivals and departures, due to restrictions on civilian airspace created by the Indian Air Force.

After ‘pilot error’, the major finding was, ‘The entire Kazakh crew except [the] radio operator took the wrong meaning of “Traffic is at eight miles, level one four zero” as the clearance for them to descend to FL-140. Such action can be attributed to their lack of proficiency in the English language.

‘None of the crew understood the traffic situation in the vicinity. This was borne out by their failure to link up… the preceding transmission to Saudia 763 asking the pilot to maintain FL-140. Besides inattention, their lack of proficiency in English language is clearly borne out.’

Language proficiency

Following the accident, The Indian Express quoted aviation officials as saying there had been 10 recent near misses in India’s skies, most involving airlines from former Soviet republics. Many of the problems were blamed on the pilots’ poor understanding of English, the newspaper said.

Besides inattention, their lack of proficiency in English language is clearly borne out.

In September–October 1998, almost 2 years after the devastating mid-air collision, India joined more than 190 member nations of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) at the organisation’s 32nd assembly in Montreal. India’s proposal to include language proficiency requirements as part of licensing was accepted and led to the formation of a working group to further study the issue.

Three years later, the language proficiency group’s recommendation to require level 4 proficiency in English (of 6 levels) for pilots and controllers internationally was adopted, with implementation of mandatory language proficiency requirements by 2011.

Captain Enrique Valdes, a former airline captain and member of the language proficiency group, said on 52, the Indian news podcast, on 9 October 2020: ‘It was India that took the initiative to bring it to the ICAO Assembly. India was the one that put it on the floor and was able to get the resolution to pass.’

Almost a quarter of a century later, are the proficiency requirements working?

Neil Bullock, an aviation English specialist and aviation English test developer, has been teaching and testing pilots and controllers and working with civil aviation authorities (CAAs) and air navigation service providers (ANSPs) worldwide since 2006. He says that since the implementation of ICAO’s requirements, with the mandating of level 4 proficiency for international crews and controllers, ‘There is certainly a greater awareness of the language and communication needs of this cohort working at international level’.

Recently he accompanied some inspectors on a random check of aircraft at an international airport. ‘I was able to talk to crews informally – multilingual, multinational crews of aircraft from bizjets to international airlines – and they mostly had a pretty good level of English which generally matched the language proficiency level given in their licence,’ he said.

Jennifer Roberts is a program coordinator in Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University’s Department of Aviation English, a co-author of the 2019 Bloomsbury publication, English in Global Aviation and has a Master in Applied Linguistics. Like Bullock, she says the proficiency requirements mean ‘more pilots and controllers are learning aviation English than ever before’ and there is a broader understanding of the role language and communication play in aviation safety.

‘[Mandating of the requirements] has created a demand from airlines, ANSPs and CAAs and the opportunity for people like me to apply our linguistics training to real-world issues,’ she says.

However, they agree there is still a lot of work to be done. Bullock argues that under the current framework, there is not enough focus on the operational context. ‘The rating scales and descriptors are not based enough on real-life communication,’ he says. ‘They are based on a rather traditional view of general plain language. The operational language has to be a bolt-on which many practitioners find challenging. So do the [requirements] really address aviation’s communicative needs?’

While aviation English has become synonymous with pilot-controller communication – understandable because of the high-profile accidents where a failure of pilot-controller communication led to tragedy (Tenerife, Avianca, Charkhi Dadri) – Bullock says there may even be a need for a broader focus. ‘It’s not just pilot-controller communication that makes the system safe – good communication is important for safety across all operators, such as maintenance personnel and ground handling.’

He would also like to see aviation communication ‘integrate wider-scale communicative competencies, such as intercultural skills, standard operating procedures and situational demands’.

English for Global Aviation argues that aviation personnel not only require speaking and listening proficiency, but also reading proficiency. ‘The full range of operational contexts in which English is required by aviation personnel includes reading proficiency and speaking and listening proficiency,’ it says.

Aviation English could possibly be built into human factors. ‘That may give it a more acceptable face,’ Bullock says. ‘I do wonder, though, whether communication, or at least language proficiency, is still seen as an isolated add-on and not a core competency of human factors.

There are no native speakers of aviation English.

‘While we can’t change the standards and recommended practices overnight, it would be good to think about how best to upgrade the system to create a greater awareness, bringing together researchers, practitioners, linguists, operational people and creating linkages to crew resource management and human factors. The whole system is interdependent.’

Roberts says the current aviation English practices are at odds with the philosophy of an industry whose mantra is ‘safety through standardisation’, with its system of standard operating procedures, ICAO standards and recommended practices.

‘The aviation industry needs access to quality curriculums, teachers, tests and raters to meet level 4 proficiency, but none of this is regulated,’ she says. ‘Across the world, aviation English is handled very differently. Until we have that standardisation, the [requirements] won’t achieve what they were intended to do.’

Researchers are working in critical areas of aviation maintenance communication, for example, on potentially safety sensitive areas such as shift handover and documentation, but their effectiveness is hampered by the lack of regulation regarding language proficiency requirements for that sector.

The International Civil Aviation English Association was established in 1991 to ‘promote the development and understanding of the use and effective application of English in aviation’. Bullock and Roberts are members of the association’s board, which is working to address those deficiencies, by developing language proficiency test design guidelines, among other projects.

Like Bullock, Roberts also says the focus needs to broaden, to consider issues such as the intercultural dynamics of aviation communication and the unique nature of aviation English. With the increasing globalisation of international aviation (seen pre-COVID-19 especially) comes a much more heterogenous mix of flight and cabin crew.

‘You may have a captain from China, a first officer from Brazil, cabin crew from the UAE, all with different cultural perspectives regarding power distance, individualism versus collectivism,’ she says.

Future aviation English standards should take these broader factors into account. ‘We need to acknowledge that aviation English is a unique register of English,’ she says. ‘It’s highly nuanced – there are no native speakers of aviation English.’

Even between native English speakers the mis-communications are apparent and have contributed to accidents and many more incident. Politics too plays a major role as each country under the ICAO system sets and enforces its own standard.

43+ years in aviation worldwide, a moderator for CRM and HF courses, and as an Aviation Psychologist with a front row aircraft seat I feel qualified to at least comment on language in aviation. It is wise in my opinion borne of experience in. the real aviation environment that 90% of ALL communications must be assumed as likely to be a miscommunication for any of many reasons. There are so many components to a seeming ly simple communication the chance of failure is very high.

Pilots are amazingly focused in my experience, especially in very automated cockpits and too many have no mental model of what is happening around them in the airspace they are sharing and which itself may be segmented to a degree that blocks building that mind map of surrounding activity.

None of what is written above is new to me and I am sure to many who have looked at this problem of decades. It is the resistance of the aviation system itself that is the greatest barrier to improvement.

Aren’t we glad that we have gone beyond the simple ‘pilot/controller error’ cause for incidents? Doing so was so limiting in incident/accident investigation. My first thoughts when beginning to read this article was where was the TCAS; where was the Mode C readout on the radar but then reading further I saw that apparently these systems weren’t in play in this case. Of course, the other glaringly obvious aspect is what are departing and arriving aircraft doing on the same track something that rarely exists today for good reason.

I agree with the previous comments particularly with lower level (both experience and altitude) pilots. Strong indications in my area (Sydney Basin ATC) are that many pilots are not developing a useful air picture.

Additionally, there are still frequent issues with language/pilot – controller communications because of a weakness in English/Aviation language capability.

29 years enroute controller, saw many incidents of communication difficulties. What suggestions do you have? Yes, we could improve

5 shall be pronounced FIFE. However, when it comes to 4, I don’t believe that everybody knows what shall be uttered. Standardisation is good when it is well defined, and it should help those who have a poor command of the English language. Another example – CLIMB or CLIMB TO is recommended or enforced according to the ANSPs managing national/regional airspace. Of course, nobody would mistake CLIMB TO 3,000 FEET and CLIMB 23,000 FEET, thanks to the transition altitudes and the big the difference there would be in this case… until the doomed day it happens… Then, as usual, decisions would be made. I remember another incident (between native English speakers) with “FOX-ECHO” (quebec-foxtrott-echo for ICAO) mistaken with a call sign. Is that so difficult to utter QFE at least “queue-eff-eeh” instead of “fox-echo”? Not to mention “GO AHEAD” which has been deleted from ICAO DOC 9432 since 2007. GO AHEAD is still widespread. Is it difficult to say a call sign, “over” or “pass your message”? What are we waiting for to enforce – and modify, if need be – the RTF standards? Another runway incursion? How many fatalities are needed to clean this out?

It is not the problem with language itself, what other people say, but with understanding what they want to say. In this case ATC meant traffic warning and crew understood it as clearance not because they could not understand words, but because they did not understand the sense.

My native language is Russian too, I live and work in Australia for 13 years and have official 6 language level, but I constantly get situations when I really lost my way in communication because someone uses some assumptions that are not known for me. It takes significant time and mind efforts to understand their idea even on ground, and in the air all this is even worse as there is no time to stop and think “what they wanted from me?”.