| de Havilland Mosquito B.XX, KB 267/AZ-E Steenburgen, Nord Brabant, The Netherlands Tuesday, 19 September 1944 |

The most important thing of all is this cockpit drill business …

All it means is getting to know the position of every tap so that you can fly the aircraft without having to look down for the controls.

– Guy Gibson in his autobiography, Enemy Coast Ahead, published 1946

The fatal crash of a renowned World War II pilot shows aviation in any era is no respecter of persons

On an unglamorous street in an industrial district of Steenbergen, in the Netherlands, a few coloured paving stones mark out a British flag. Grumbling DAF trucks coming and going from a farm machinery dealership grind past this unassuming memorial every working day. Occasionally a tourist pays a contemplative visit.

The reason why is in the name of the street, built on what in 1944 was open land: it is Mosquitostraat. Nearby are Gibsonstraat and Warwickstraat. It is the spot where Wing Commander Guy Gibson and Flight Lieutenant James Warwick died when their de Havilland Mosquito crashed on the night of 19 September 1944.

Once more, into the breach

Gibson had been the leader of the bombing raid by Royal Air Force 617 Squadron that smashed 2 dams in Nazi Germany in May 1943. His name would become famous after the 1955 film about the raid, but even by 1944 he had become a celebrity of war. He had been taken off operational flying after the dam raids, which had been his 174th combat flight, and awarded the Victoria Cross. Since then, he had occupied his time with an official morale-raising trip to the United States and Canada, in the company of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who informally gave him the nickname ‘Dam-buster’, attended staff college and been posted to the Royal Air Force Directorate for the Prevention of Accidents.

This post was probably a cover for him to write his wartime autobiography. An officer who visited him there found him unhappy and long-haired and, in a letter to a friend, Gibson described the posting in coarse language. The D-Day invasion of 6 June 1944 spurred Gibson to apply to return to operations. By August he was Base Air Staff Officer at 54 Base in Lincolnshire, in northern England. His duties were mainly planning and liaison and he appears to have been under orders not to fly on raids. This did not suit him. An Australian navigator on base described him as seeming like a lost soul. But he wangled his way into observing on 4 short range daylight attacks on French targets and made a few non-operational flights.

On 19 September the 54 Base commander was off-base as was the commander of nearby 627 Squadron, which flew de Havilland Mosquitos as target-marking aircraft. Gibson had logged 9 hours 35 minutes in a Mosquito since his arrival, under instruction/supervision including a session practising the dive‑bombing technique that target marking required. That afternoon an order for a raid came through and as senior officer on base, he took his opportunity – taking over an aircraft, whose regular crew were not pleased.

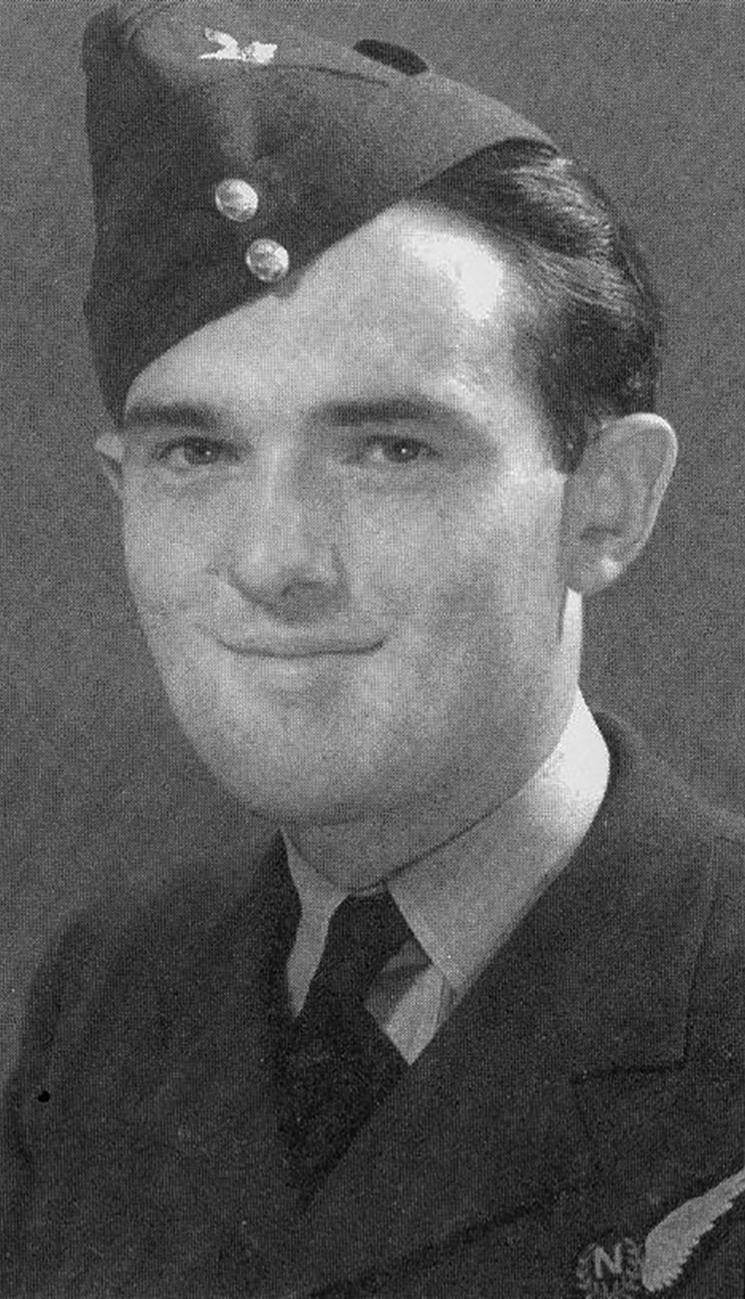

Gibson had already rounded up a navigator. 54 Base’s navigation leader James Warwick got the job – whether voluntarily, by request or under a direct order will never be known. A Northern Irishman, known by the affectionate, if predictable nickname of ‘Paddy,’ he was skilled and experienced in navigation after 2 tours of duty in Lancaster bombers but had never flown in a Mosquito. Like Gibson, he was off operations. They took off into dim twilight at 1951 hours, destination Mönchengladbach in western Germany.

About 2230, witnesses in Steenbergen saw an aircraft approach the town at low altitude. Several of them noted a light in or near the cockpit, one described it circling. ‘Most accounts agree the Mosquito entered a steep dive in its last seconds,’ Gibson’s biographer Rickard K Morris writes. The aircraft went into a field northwest of the town. There was little recognisable of it or its crew the next morning.

The engines had buried themselves several metres down in the moist polder soil and the wooden airframe was smashed and burnt beyond recognition. Only the grotesque discovery of 3 hands provided any clue about how many were on the aircraft. The people of Steenburgen held an ecumenical service to bury the airmen in a single coffin.

Mystery in the polder

All the evidence about Gibson and Warwick’s crash is circumstantial. The wreckage of the aircraft, when it was recovered in 1985, yielded no clues or signs of battle damage. The remains of the airframe had been unsentimentally disposed of 41 years earlier, in a time of plentiful aircraft wrecks, sad memories and a desire to get on with life.

All the evidence about Gibson and Warwick’s crash is circumstantial.

617 Squadron Association official historian Robert Owen says there are several possible scenarios: ‘There’s a lot of evidence that suggests fuel starvation,’ he says, “but it’s possible that Gibson or Warwick may have been wounded or Warwick killed, or the aircraft damaged by anti-aircraft fire, or the controls may have been damaged. Given that they were returning at low level it’s extremely unlikely that they were shot down by another aircraft.

‘The witnesses on the ground hear the aircraft approaching. It sounds to be running roughly, which suggests an engine problem, possibly caused by a fuel problem. Then they say the engines cut and picked up and there was a jet of flame and the aircraft rolls and dives into the ground.

‘The thinking based on most witnesses was, fuel starvation, a mad scramble in the cockpit to get the fuel right again, engines cut through fuel starvation, fuel flows again, there’s a restart, surplus of fuel which goes to the exhausts, a backfire of flame, which happens with a rich start on a Merlin [engine]. If one engine picks up before the other, you are in an asymmetric situation, which could cause a roll. If you’re not expecting it, you’re low and you’re not experienced in handling the aircraft, you’re not going to catch it.’

Witnesses can be unreliable – in countless civil crashes they have described aircraft being on fire when wreckage proves to be unburnt. But Owen says air-minded Dutch civilians in 1944 would have had familiarity, if not expertise, with dozens of aircraft flying over them every day. And the witnesses’ stories are broadly consistent.

In the eyes of many this was an accident waiting to happen.

Biographer Morris summed up the mood at 54 Base when he wrote, ‘In the eyes of many this was an accident waiting to happen. The sortie had been organised in haste. Gibson was ill prepared. He was flying an unfamiliar aircraft. His navigator had not operated for months. Both were undertaking complicated duties for which they had not rehearsed.’Owen says Warwick’s total lack of experience in the Mosquito adds a human factors dimension to the explanation.

‘You’ve got an experienced navigator, flying with a pilot who is possibly slightly in awe of because of rank, status and reputation. It’s what is now called a cockpit gradient,’ he says. ‘However, the pilot doesn’t have a lot of experience on type – and the navigator isn’t able to question that. He’s not going to have a problem with navigation. But he is going to have a problem with the working environment. And he’s now got other new roles, flight engineer and wireless operator. His workload is increased, in categories that are new to him. He’s going to be working under stress.

‘And the physical environment of the Mosquito is different. Warwick’s experience is on Lancasters, so he’s used to working at a reasonably sized navigation table. He now finds himself squeezed, sitting half behind the pilot with his charts on a small kneeboard.

One source suggests Warwick tried to learn all he could before take-off. Dutch historical author Jan van den Driesschen wrote how an engineering officer at 627 Squadron related how he had described the Mosquito’s fuel system to Warwick in a brief tutorial which was interrupted by an impatient Gibson. ‘During my instructions I was rudely more or less thrown out of the aircraft by Gibson,’ the engineering officer said.

The fuel transfer switches in a Mosquito B.XX were on the rear bulkhead of the cockpit. Owen says that location added considerably to the difficulty of the task. ‘Bearing in mind the confines of the cockpit, it’s a bit like reaching into the back seat of the car while moving – very difficult,’ he says. ‘Imagine then doing it in the dark, under operational conditions and possibly under time pressure because you’ve been caught unawares or preoccupied with another task because so many things are new on this flight.

‘It’s total speculation but all these what-ifs and maybes add up to a picture of unfamiliarity and high workload.’

Technicalities

Warren Denholm can add a little precision to the speculation. His company Avspecs Warbird Restorations of Ardmore, New Zealand, has built 3 Mosquitos from de Havilland’s blueprints.

‘There’s not much to it from a pilot’s perspective,’ he says about the aircraft’s fuel system.

‘You take off on main tank, switch to the outer tanks and deplete them before switching back to the mains.’

The main inboard tanks feed into a single gallery that feeds both engines, Denholm says, while the outer tanks only feed that side’s engine.

Denholm also notes a possibly significant engineering detail. Canadian-made Mosquitoes such as KB267 used American Packard Merlin engines which had a pressure carburettor – in effect, a single-point fuel injection system. Restarting these involved an additional step – switching on a fuel pressure pump – compared to restarting carburettor‑fed Merlins. Gibson had done the majority of his scant Mosquito hours on Packard Merlin B.XX Mosquitos. But his most recent flight before the raid had been in an earlier B.IV version using British carburetted Merlins.

There is little to be gained from attempts to reconcile Gibson’s flight path and the Mosquito’s fuel capacity with the possible tank change point and the location of the crash. There are too many variables, including how full the tanks were, the flight path flown, winds and how long Gibson loitered over the target.

Battle damage could have changed the fuel management situation, Owen says. ‘I know they had self-sealing tanks, but self-sealing wasn’t perfect, there could still have been a slow leak or a nicked fuel line and either could have led to a fuel starvation at an unpredicted time in the flight.’

Shootdown theory

In 2011 a wartime history magazine published a story based on the taped testament of a Lancaster mid-upper gunner, Bernard McCormack, who died in 1992. McCormack said he had been told that an attacking aircraft he had reported as a German Junkers 88, had been Gibson’s Mosquito. Newspapers and broadcasters adopted the shootdown theory uncritically, but Owen is not convinced. ‘The combat report from that night – the original document – does not equate with the tape-recorded recollection,’ he says.

‘The combat report describes a Junkers 88 firing on the Lancaster. That’s not Gibson – his aircraft had no guns,’ Owen says.

Gibson’s experience in the air force was rare. He was a former bomber pilot and a former night fighter pilot. ‘He of all people would have been wary of joining a bomber stream on way home from raid,’ Owen says.

Owen says it was also unlikely Gibson would have been high enough to encounter a returning bomber.

‘We don’t know exactly what route Gibson took but I think we’re more certain on the altitude, which gives a problem to the shootdown theory,’ Owen says. ‘We know that Gibson rejected the instructions to return at medium altitude. He told another officer, “I’m coming back at low level”. That fits with what the witnesses saw at Steenbergen. The aircraft is at low level, approaching from Germany.’

The specifics of the case are as obsolete as the Mosquito, but the generalities are as timeless as that elegant design.

Lest we forget

What can we learn from this 78-year-old crash? The specifics of the case are as obsolete as the Mosquito, but the generalities are as timeless as that elegant design. It’s a vivid reminder of the importance of fuel management, flight planning, type experience, and how the sky in war or peace is no respecter of persons. Looking back, the influence of organisational culture is starkly clear. Death from enemy action was a frequent visitor to wartime RAF (and RAAF) squadrons, which in the stoic spirit of the time saw their role primarily as fighting. And fighting, unavoidably meant dying. Added to the losses of war was the pervasive 1930s notion that aviation was an inherently dangerous activity (which it is, but in the modern world its risks are understood and managed). A safety culture of risk assessment and hazard mitigation stood little chance of thriving in this environment. Despite this, some pilots made safety a personal priority; a successor to Gibson’s command at 617 Squadron, Leonard Cheshire, had a practice of sitting blindfolded in the cockpit of his aircraft reciting drills and learning the position of controls by touch. But, as Owen notes, under wartime necessity, Cheshire also flew new aircraft types into action with what modern instructors would consider shockingly little type experience.

The other killer factor still out there is emotional bias and its effects on decision-making. Gibson wanted to fly on ‘ops’ again, very badly, and this desire undoubtedly affected his judgement. Morris speculates part of his fierce desire to return to the war may have been because ‘Churchill had given him unpublished information about the behaviour of the Nazis and the industrialised murder of the Jews’. Motivations do not come any more noble, and Gibson, like all who flew in the bomber offensive, was brave beyond modern comprehension.

The other killer factor still out there is emotional bias and its effects on decision-making.

Our emotional biases in peacetime are petty by comparison, and therefore should be easier to examine and discard. No matter how much we are tempted to take off into dark and stormy – but peaceful – skies, or stretch our qualifications and experience to breaking point, we have no dam-busting excuse.

Comments are closed.