In this unexpected and scary incident, the pilot reaches for something familiar to use in an unusual way.

I was returning from Condobolin to Moorabbin in a Cessna 182RG with 2 passengers. The weather forecast had been satisfactory and I had filed and flown a VFR plan without any difficulties.

We had passed Kilmore, planning to track to Moorabbin via Yan Yean. Cruise altitude was just below 3,000 feet; a 65 per cent power setting of 23 inches manifold pressure and 2,100 RPM was giving us the advertised lAS of 135–140 knots.

The only cloud was high above us, while there was slight to moderate convective turbulence. The wind was steady from the north-west at 10–15 knots. Immediately before the incident we unexpectedly encountered heavy convective turbulence which resulted in the Cessna sustaining 2 or 3 rapid and very hard applications of positive G. These applications were strong enough to make the aircraft’s structure creak.

At that time I had my left hand on the control wheel and was resting my left elbow on the door-mounted arm rest, while my right hand was on the throttle. Because of the severity of the turbulence, it was my intention to close the throttle and reduce IAS.

Suddenly, there was a very loud sharp noise and a flood of light poured into the cabin. The cockpit was scoured by a blast of air and a deafening roar – papers and loose clothing began to fly about. This was accompanied by the aircraft yawing and rolling to the left. At the same time, I was startled to notice that there was nothing between me and the ground – the left-hand side of the aircraft seemed to have disappeared.

Suddenly, there was a very loud sharp noise and a flood of light poured into the cabin.

My first thought was the aircraft had suffered a structural failure, particularly as it did not immediately respond to control inputs (later I concluded this was probably due to the effect of the continued turbulence). In an attempt to regain control, I closed the throttle, extended the landing gear and slowed to 90 knots. Having established control, I began a descent, put the mixture to rich, applied power, lowered 10 degrees of flap and maintained 85 knots. Although skidding to the right, the aircraft remained controllable. The noise level was very high.

At this stage I remembered my rear‑seat passenger and, looking back over my right shoulder, was relieved to see he was still there. I declared a PAN to Melbourne, advising them I thought the left-hand door had completely separated from the aircraft. Just after this call, I noticed that the door was still with us – it was hanging by its restraining strap (which is meant to prevent the door from opening too far) and appeared to be resting on the undercarriage leg or the wing strut. The combination of these restraints and the air loads seemed to be holding the door in place. However, I noticed that when I applied rudder to correct the aircraft’s skid , the door began to flap alarmingly. Needless to say, I did not persist with attempts to remove the skid.

The fact that the door was still on the aircraft introduced a new factor as well as those I already had to assess before deciding what to do. Specifically, I was now concerned that if the restraining strap broke, the door might fly rearwards and strike the empennage, making the aircraft uncontrollable. There was also the possibility the door could injure someone on the ground if it fell away.

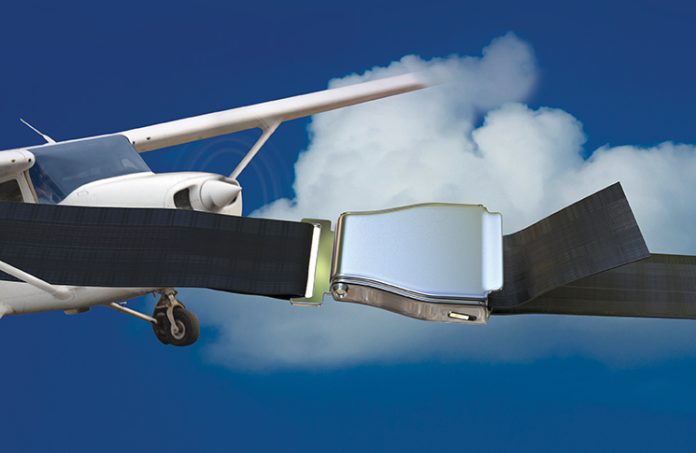

In an attempt to circumvent both of these possibilities, I removed my belt, passed it through the door handle and knotted it around the aircraft’s seat belt attachment. I was now in a position to consider how best to get the aircraft on to the ground.

Whittlesea airstrip was the closest available; however, I was not familiar with the airfield and did not know the radio frequency for its traffic. Further, Whittlesea does not have the emergency services that are available at Moorabbin. I was also concerned the disturbance to the airflow caused by the door might create difficulties in the approach or the door might come loose on landing and damage the landing gear.

Consequently, I elected to continue to Moorabbin and advised Melbourne of my intentions. Ground-air communication remained very difficult – as well as those inside the aircraft – because of the high noise level.

I tracked to Moorabbin OCTA, avoiding built-up areas as far as possible. A straight-in landing for Runway 17C was approved, and only 20 degrees of flap was selected to minimise aircraft configuration changes. The landing was poor because of my nervousness and the fact that I did not trim out the drag-induced yaw on finals but rather tried to hold the aircraft in balanced flight by use of the rudder. Although the landing was not as smooth as I would have wished, it was safe enough, and I was able to taxi the aircraft to its tiedown point.

Post-flight inspection revealed the pin on the upper door hinge had sheared, allowing the leading edge of the door to protrude into the airflow – then 140-knot slipstream ‘peeled’ the door open. The restraining scrap stopped the aft movement of the door, while the wing strut stopped it dropping down

Lesson learnt: This pilot managed to overcome the ‘startle’ effect, remembered to ‘aviate’ first, came up with a temporary fix to the problem, considered various landing options and put down safely. The lesson learnt is you can handle unpredictable situations by relying on your training, intuition and life skills.

Interesting story, but Whittlesea airstrip ceased to exist sometime in the late 90’s/early 2000, and was there ever a 17c runway at Moorabbin?

Look theses stories are interesting but how about dating them so they are in the right context.