A fatal impact during a training flight involving two experienced pilots prompts Adrian Park to consider the relationship between rules, procedures, compliance and human performance.

The words that spell out rules and procedures are dead marks on a page until they are embodied and lived out. This is a truth as ancient as Plato who said words have, ‘The appearance of wisdom but not the reality’. Therefore, I believe CASA’s latest safety slogan is a good one: ‘Safety is in your hands’.

But of course, the reality is, whether we be frontline practitioner, boardroom manager or federal regulator, we all carry around 2 versions of ourselves: what we could usefully call our ‘best’ and ‘worst’ versions.

A moment of self-reflection is all it takes to confirm the existence of our worst version. And the scary thing is we’re not talking about Jekyll and Hyde, or the werewolf. Your worst self is not some hairy monster that howls at the moon: it’s you at 90 per cent of optimum. You still look and sound the same, you may even feel the same, but you lack the edge.

We could all testify about how this diminished self emerges on the back of stress, fatigue, distraction, workload, illness, complacency, conflict and various other performance-sapping circumstances. Sure, most of the time our worst version is not the agent of an accident but, with only a slight tweaking of circumstance, it easily might have been.

An important question then arises: how can safety rules and safety procedures account for both the worst and the best versions of ourselves, without becoming hopelessly congested or gargantuan?

They are among the most demanding a helicopter pilot can experience – we used to call them ‘black hole’ approaches.

I have spent the last 6 years trying to answer this question. I’ve approached it by analysing 50 years’ worth of accident investigations from those publicly available at the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) website. Collectively, from the tragedies of real accidents (1968–2021), I have identified what I call 10 red rules.

The ‘red’ refers to the way the rules are, in a sense, written in blood and the way they represent the essential principles by which aviation professionals operate safely or, in their absence, do not.

Time doesn’t permit full treatment of the 10 but the most influential are:

- situational awareness – knowing what is happening

- judgement – knowing how to respond

- proficiency – being able to make the right response

I call these the royal 3 because together, in over 50 years of Australian aviation investigations, they so evidently govern nearly all successful flights and, in their lack, are implicated in nearly all accidents. These are ‘royal’ safety rules because they are the rules that rule them all.

There are many elaborate applications of the red rules but the simplest and the most important is this: if we want rules and procedures to empower the best safety versions of ourselves, we need rules and procedures that generate excellent situational awareness, great judgement and high proficiency.

Into a black hole

This is emphasised by a recently released ATSB accident investigation. It involved a night approach by an EC135 helicopter to a bulk carrier in near-zero illumination near Port Hedland.

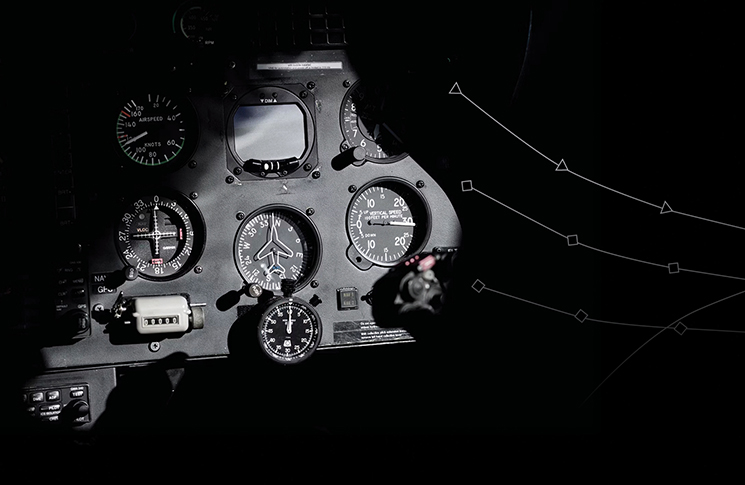

As anyone who has flown these approaches will tell you, they are among the most demanding a helicopter pilot can experience – we used to call them ‘black hole’ approaches. This is because the darkness of the sky, combined with the darkness of a still ocean, conspires to bring about the ominous absence of any useful horizonal or terrestrial cues with which to judge up from down, fast from slow, descent from ascent.

In the merged darkness of sky and ocean, the approach must be manually flown relying almost entirely upon the instruments. To conduct a safe approach, the pilot must constantly read the aircraft speed, rate of descent, altitude, distance from the ship and so on, to build a mental picture, while monitoring the instruments.

The pilot has to make judgements about that mental picture and adjust the controls as the aircraft descends closer to the unseen ship and the unforgiving ocean. In the words of the Australian poet Clive James this is flight in ‘a token world whose import is immense.’ And, since it is a helicopter and, more often than not, the night winds change markedly through the descent, the correcting and adjusting are almost continuous.

In short, such approaches demand a high degree of situational awareness, high proficiency and sound decision-making – they demand the team’s best version of themselves. And, for most operations, this is what the approach gets. The requisite proficiency is available, situational awareness is maintained, sound judgements are made and another successful flight is logged.

But, on the night of 14 March 2018 near Port Hedland, the confluence of 4 significant factors significantly compromised the team’s ‘A game’ as they conducted marine pilot transfer training.

First, the pilot under supervision was getting back into flying after 7 years away from dark-night marine pilot operations and was significantly different to the one the pilot had just left. The previous 7 years of flying had been in a single-engine helicopter with much less complexity and automation than the twin-engine EC135.

Second, a tight training schedule meant the first night flight was not within the congenial environment of an airfield but the demanding environment of a dark ocean approach to a bulk carrier.

Third, the same tight training schedule meant both pilots were experiencing the effects of fatigue and, for the pilot under supervision, this was to a performance-degrading degree.

Finally, design factors meant the instructor was sitting on the left side of a single-pilot configured helicopter without easy reference to key performance instruments. To see such instruments, the instructor had to look across to the right-hand pilot’s instrument cluster.

Under these conditions, the flight was primed for the emergence of the team’s worst version, as it would for any team in the grip of similar conditions. This quickly became evident in the first approach.

Having established the aircraft on final descent and having decoupled the ‘upper’ modes of the autopilot, the pilot under supervision was having difficulty ‘flying the line’. At the same time, the instructor, without instrumentation on that side of the cockpit, was having difficulty readily detecting the difficulties of the pilot under supervision.

The net result for the first approach was a too steep descent. And, adding to the difficulty, was an increasing crosswind as the aircraft descended. This meant the 6 degrees of right drift at height turned into nearly 20 degrees of right drift at the lower levels. At about 500 feet, realising the aircraft was descending at 900 ft/min (nearly double the normal rate of descent), the pilot began a go-around.

Halfway around what would normally be a level base turn, the airspeed had decayed to 30 knots and the descent rate was increasing towards a deadly 1800 ft/min.

A go-around in circumstances like this isn’t a rare thing. As discussed, these approaches are among the most demanding a helicopter pilot can experience. The sure way to get better is to practise.

Therefore, the pilot under supervision completed the go-around, turned the aircraft onto downwind at 1,100 feet and prepared for the next approach – and it was here the decisive moment occurred.

Instead of the downwind altitude being maintained either manually or by utilising altitude-hold, the aircraft began an unintended and unmonitored descent, first at 500 ft/min, then 800 ft/min, and the descent continued increasing into the base turn.

Halfway around what would normally be a level base turn, the airspeed had decayed to 30 knots and the descent rate was increasing towards a deadly 1800 ft/min. That this went undetected might be surprising but, on such nights over water and at slower airspeeds, it is almost impossible to discern by feel or sound the difference between 200 ft/min and 2000 ft/min.

The only indications are a few changing numbers among many other numbers on the primary flight display. Normally, when human performance is at its best, these numbers are read and acted on but, on that night near Port Hedland, with a cognitively loaded, distracted and fatigued crew, the instrument readings were seen but not perceived.

This state of imperception continued until the instructor, looking across the cockpit and seeing the descent but not fully appreciating how dire it was, called for an increase of power. The pilot under supervision might have heard the call but, still mentally catching up with the aircraft, did not respond. The aircraft continued to rapidly descend and, at 300 feet, normal cockpit sounds were disrupted by ‘check altitude, check altitude’ from the radar-altimeter annunciator.

Halfway around base, the tinny voice from the annunciator was unwelcome. It caught the attention of the instructor who took control and began to apply power but not enough – the rate of descent decreased a mere 300 ft/min, from 1800 to 1300 ft/min.

With much more inertia than applied power, the result was inevitable. A few seconds later, the aircraft hit the water and rolled inverted, to be held in place upside down by inflated floats. The instructor managed to escape the aircraft through a broken windshield but

the pilot tragically did not.

Who are you really?

It is easy when reading an accident report like this to inadvertently project our best version into the event. But this is to erroneously compare our best version with someone else’s worst version. To be fair, and realistic, we would do far better to project our worst version into the accident because the truth is, our worst version is only one lost night’s sleep or one long absence from flying or one excessively-stressed moment, away.

Accident investigations like Port Hedland can be seen as ‘what if’ biographies of ourselves on our worst night in our worst state. That’s what I’ve seen in the 50 years’ worth of accidents I’ve studied. But I’ve also seen something else that far outweighs the accidents: literally tens of thousands of incident-free flights.

Therefore, the logical conclusion is, in the great majority of flights we are bringing our A game and the best version of ourselves to the complexities and demands of aviation. Which brings us back to our original question: how can rules and procedures deal with both the worst and the best versions of ourselves, especially when we continue to carry around our accident-primed worst version.

The important answer, and the one with which I will conclude, is that rules and procedures, to be authentically safe, must be people-empowering.

Of all the rules and procedures we write, if they don’t tangibly empower the qualities of excellent situational awareness, great judgement and high proficiency – the rules and procedures might be ‘safe’ by name but they will not be safe by nature.

Rules and procedures, to be authentically safe, must be people-empowering.

The Port Hedland crew had many rules and procedures but such rules and procedures could only, ironically enough, be enacted by a team with the three qualities mentioned. Therefore, rules and procedures must never congest, complicate or confuse the humans at the centre of aviation who – whether they be frontline practitioner, boardroom manager or federal regulator – are called to consistently respond and adapt to the complicated safety demands of the real world.

After 28 years flying, as well as 6 on safety research for a PhD, I could say many complicated things about safety rules and safety procedures. But one simple thing strikes true: it’s not rules and procedures that primarily make us safe – it’s empowered people.

Plato’s wisdom is a good place to return to conclude: for safety’s sake, in the writing of many words – whether expositions, regulations or policies – let the right amount of words bring people-empowering wisdom, not its complicated appearance. Then we will truly be able to say to our aviation teams – safety is in your empowered hands.

Before we heap ALL responsibility onto the two pilots in the EC 135 night approach accident described above it is critical to any analysis to include as factors, possibly primary factors, the environment surrounding the operation. That is beyond the black hole approach, such vis., winds and sea etc.

1. What forced this crew to do this flight at that time in those conditions?

2. Was time pressure such as aircraft availability or instructor availability a factor?

3. Why was training authorised with sub-standard equipment (instrumentation and controls) AND the worst conditions for first night training mission conducted on a ship instead of an airport?

4. What did company procedures for this training require – were there any and were they scrupulously observed in reality?

5. What were the likely consequences if the training had been cancelled for any one of the points above?

The pilots bear a part of the responsibility though NOT all of it. There were a lot of factors shouting ‘stop the flight’ so the reasons to continue must be determined. Without considering all the possible reasons to pursue this operation the true factors leading to unnecessary deaths will never be known. It is too easy and tempting to just pin the tail on the dead donkeys and think thats it then.

Would really appreciate the ten rules, with red letters as appropriate

What a well-written article…bringing to life such important concepts which so-often pass unsaid. I have eagerly read other articles by this author – by heavens he is good. A very sincere “well done” and thank you.