| Boeing 707, N748TW/Lockheed L-1049C Super Constellation, N6218C, over Carmel, New York State, US Saturday, December 4, 1965 |

The collision of 2 airliners in the US, 57 years ago, is a story of superlative airmanship, and a solemn reminder of the limits of see-and-avoid as a defence against collision.

Patricia Skarada didn’t mind the crowding, the noisy obsolete aircraft, the absurdly short time to get drinks service done, or even the hassle of having to sell $14 tickets onboard the Boston to New York-Newark shuttle as though she were a bus conductor.

Working on the crowded, unglamorous and frequently delayed service was the quickest way to hit her maximum duty time of 40 hours a month as cabin crew, after which she was free to see the world with Eastern Airlines’ generous staff pass privileges. It was a life beyond comparison with the career in accountancy her father had wanted for her.

‘Other than the demands of the job, I didn’t have anything else to worry about,’ the now Mrs Hartmann says.

At the pointy end of the Lockheed L-1049C Super Constellation, Emile Greenway would have counted himself similarly fortunate, had he allowed his mind to wander from the duties of flight engineer. The hard decision to finance his IFR training by trading his beloved Ford Thunderbird for the mundanity of a Ford Falcon had led here. He had come a long way since towing airborne banners above Florida in a Piper Cub, and his goal, the captain’s seat, was literally close enough to touch.

Today was a good day because he was on the flight deck with a captain whom he respected, and who respected him. Charles J White, 42, known as Chuck, was easier to get along with than many of his colleagues, one of whom used to place a sign on the glareshield that declared ‘the captain’s word is law!’

‘There were a few captains in Boston I didn’t care to fly with, but Chuck was a straight shooter and a nice person to fly with,’ Greenway, now 85, remembers. The first officer was Roger Holt.

The first 40 minutes of the flight were uneventful and by 4.18 pm, the Constellation was flying through cloud tops at 10,000 feet, approaching a VORTAC navaid at Carmel, in New York state.

‘We collected fares and I tallied everything and stored it,’ Skarada says. ‘We sat down for a few minutes on the jumpseat and all of a sudden there was a large bang over the tail, then a rapid upward motion which pushed us down into our seats. It sounded like the aircraft stalled, it banked to the left, then came gunning of the engines, very hard.’

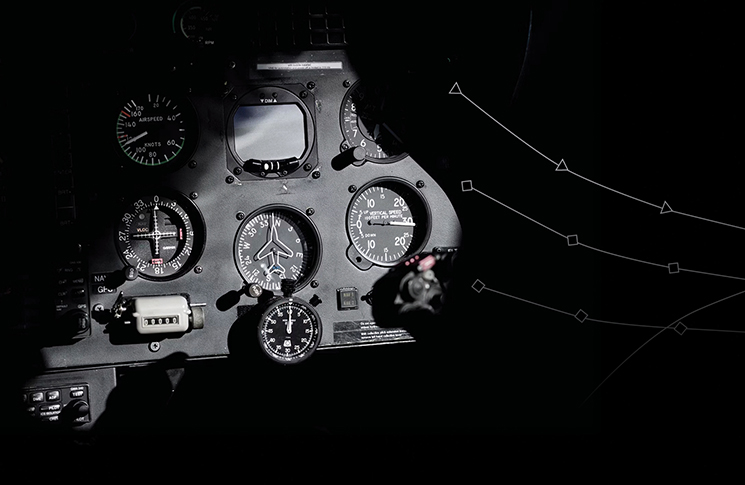

Greenway had a clearer idea of what was happening, even if the location of the flight engineer’s station meant he saw nothing of the Boeing 707 that had appeared without warning at their 2 o’clock position. ‘I didn’t see any of it. On a Constellation, the flight engineer sits a step down from the pilots. If you look through the windshield, you’re looking up,’ he says. ‘But I did feel a bump. It felt like the landing gear coming out, nothing more.’

For a few dragging seconds as they continued to climb, it seemed they may have avoided or only grazed the other aircraft.

‘Nothing drastic happened – then we lost the flight controls,’ Greenway recalls. ‘I saw the lights coming on showing low pressure on the pumps and we were out of control.’

The Boeing 707, a Trans World Airlines flight from Chicago to New York, had also banked hard and now entered a steep dive. But its crew regained control, declared an emergency and reported to New York Centre they had collided with another aircraft. They were vectored to JFK Airport and, after a wide 360 degree left turn, landed about 20 minutes after the impact.

It was remarkable flying by captain Thomas Carroll, first officer Leo Smith and flight engineer Ernest Hall. About 7.6 metres (25 feet) of the outer left wing was missing but there were no injuries to any of the passengers and crew. Several of them in the left‑hand seats had indelible memories, though, of seeing the Constellation flying towards them in the few seconds before collision.

Meanwhile, the Constellation was descending out of control through the clouds. ‘Have you ever had a dream where you were falling through a hole and couldn’t stop yourself?’ Skarada says. ‘That was the sensation. And everything was happening so fast.’

Greenway made an emergency radio call (not a mayday, which was the captain’s prerogative) to New York Centre, mindful of how a friend of his had died without explanation in an airliner crash the previous year. ‘I vowed if ever I was in that position, I would call,’ he says.

Cabin rebellion

A reconstruction by the US Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) found initial contact had been between the left outer wing of the Boeing, and the right-hand outboard vertical fin and stabiliser tip assembly of the Constellation. The wing then passed, leading edge first, completely through the Constellation’s horizontal stabiliser.

‘I guess we got into a dive,’ Greenway says. ‘Although I don’t specifically remember that.’ But he distinctly remembers Holt making the suggestion that saved them.

‘Roger said, “Maybe if we add power that might help”, so he and Chuck pushed the power up on the 4 engines, the nose lifted and we came up to somewhat of a level flight.’

Captain White found he could maintain the Constellation’s airspeed between 125 and 140 knots and was able to lose altitude by reducing engine power, producing a sink rate of 500 fpm. He could make wide flat turns by throttling up the outer engines on each side. ‘He would take [the throttle of] number one engine, increase the power and we’d turn to the right,’ Greenway says.

As control returned, a focused calm settled over the crew.

‘There wasn’t a whole lot of talk,’ Greenway says. ‘I wasn’t too upset. I was just trying to do what I could. It was a case of, “What do I have to work with?” When they started playing with the power, I flattened out the pitch to METO [maximum except take-off] power and I brought the props to 2,600 rpm.’

It was a different story in the cabin where Skarada and her colleague Kathleen Depue had to deal with panic among the passengers.

‘The captain came on the PA telling us there was a collision and to prepare for a crash landing,’ Skarada says. ‘I was knocked over when people ran towards the tail section – they all thought that would be a safer place. It was throwing off the balance of the plane so I picked up the PA and told everyone to sit down and read the emergency card in the seat back pocket. I thought giving them something to do would help.’

In the back of her mind, Skarada was amazed by how, at 22, and slightly built, in accordance with Eastern’s cabin crew recruitment policy, she was speaking with stern authority to people twice her age. ‘You just know it has to be done or things are going to get worse,’ she says. Her most recent training the previous month was fresh in her mind. ‘In a panicked state, people are more inclined to follow a very stern command and that’s something that has to be taught.’

Field of valour

As he worked, Greenway heard White and Holt in a dispassionate discussion of the pros and cons of ditching in a lake that came into view.

There were few good landing places among the wooded outer suburban hills of the New York/Connecticut border. Their circling descent had taken them over Danbury airport, but they were too high for an approach. As they descended near Ridgefield, Connecticut, the best of a bad bunch of options appeared in the dim afternoon light, and they took it: a sloping field bounded by stone fences.

According to a breathless Reader’s Digest story published the following year, 3 boys walking across the field had to run as the Constellation loomed above them, narrowly clearing a farm building.

As the ground rushed up, White executed an extraordinary and inspired act of airmanship. He ignored instinct and precedent and pushed the throttles forward, surging the engines briefly. The result was a perfectly timed pitch‑up that brought the aircraft’s belly parallel to the upslope. ‘Everybody on that plane owes him everything,’ Skarada says. ‘Had he done it earlier the aircraft would have stalled, any later and it would have flown nose‑first into the ground.’

As the ground rushed up, White executed an extraordinary and inspired act of airmanship.

Greenway remembers how ‘we sort of flopped on to the ground.’

The CAB investigation found the aircraft had hit a tree 14 metres (46 feet) above the ground. About 75 metres farther, the left wing struck a tree trunk and separated from the aircraft about the time the fuselage contacted the ground.The fuselage continued for 215 metres and broke into 3 pieces, with the front spun around to a nearly reciprocal heading, ‘like a hinge’ reports said. All 4 engines separated from their nacelles.

Fire, panic and pain

Skarada was now carrying out that part of the job that all cabin crew train for but very few are required to experience. Memories come tumbling out of her.

‘The impact threw me forward, even though I was in the crash position, so I hit my head on the seat in front of me and was knocked out for a few seconds. The seat belt was so tight that it injured my stomach. It was black and blue. But I knew I had to get to work.’

The first thing she saw after returning to awareness was flame dancing over the cabin walls.

‘All the fire that came into the fuselage hugged the windows. Within seconds of landing, the inside of that plane was a firepit, and filled with black smoke like you wouldn’t believe,’ she says.

‘I still have nightmares viewing a woman who was burned over 95 per cent of her body; she was talking but her clothes were melted into her body.

‘The people in the tail section assisted me in trying to open the main door. But the impact had jammed the door. Then Kathy screamed she was getting out through a break in the middle of the cabin and I directed all the fellas to go up front and they stepped out the opening. I felt I had to clear the cabin because we had oxygen bottles on board and I was afraid they were going to explode.’

A surge of adrenalin masked her injuries: 4 fractures of the lower lumbar vertebrae and internal bleeding. Regardless, she returned to the cabin, calling to anyone left inside. ‘I got up and walked and lifted a baby, carried it out and couldn’t understand why I was hurting so much,’ she says. The baby’s mother, who had been frozen in panic, followed her out.

At that point she heard Kathleen Depue calling for her. ‘She was lying on the ground. I went over to her and just bending over, the pain was so severe in my back I fell.’ Her part in the evacuation was finished.

Greenway, seated sideways at the engineer’s panel, was slammed into the back of the first officer’s seat by the impact. ‘It ripped my left ear half off. It was hanging down,’ he says.

‘The only thing I remember is sitting on a stone fence. A woman came along and she sat on the fence too. She was shaking and I took my coat off and gave it to her.’

Greenway’s overcoat caused him to be misidentified as the captain, Charles White, who was probably dead at that time. White’s precise movements after the crash are not known but Greenway thinks the captain helped him and Holt out of the flight deck.

It was a tribute to White’s skilful landing that most passengers were able to walk, stagger or crawl from the wreckage. None of the seats had collapsed into each other in the concertina of people and structure that often marked crashes in that era. One passenger remained in the fuselage because his friction-type seat belt had jammed and White re‑entered the aircraft to help the young man. We know this from another passenger who also tried to help but left as the smoke thickened. Smoke inhalation killed White and the young man. Another man and a woman died in hospital.

Information and illusion

The 2 aircraft had been assigned different altitudes and, until just before the collision, had maintained these. The Constellation had been assigned 10,000 feet, while the Boeing 707 had been assigned 11,000 feet. The CAB investigation examined the altimeters of both aircraft and found all of them to be working satisfactorily. The 2 aircraft’s marginally different QNH settings and worst-case assumptions about static leakage in the altimeters could only generate total altitude errors of less than 200 feet, not enough to explain the convergence.

The CAB report found the collision resulted from a human cause. The horizon formed by the cloud tops had not been smooth but sloping, ‘with some “cauliflower” type buildups protruding several hundred feet above the general cloud tops.’

This had caused an optical illusion, the report said. ‘With higher clouds behind TW 42 [the 707], the first officer [in the Constellation] would receive an impression of an aircraft on or very near the apparent horizon. In the small amount of time that he had to judge the separation of the two aircraft, he had no visual aid to assist him in determining the true horizon and the build-up of clouds toward the north would present a false horizon on which to base his analysis of separation.’

Had the Constellation dived, the aircraft would have gone into solid cloud and the crew would have had no way to observe and evade the converging traffic if it was also entering the clouds.

Holt, the first officer, made an error that at the time had seemed the right thing to do. ‘He initiated the pull-up but I can’t blame Roger because he had less than a second to make a decision,’ Greenway says.

A court case against ATC 5 years after the crash was unsuccessful. New York Centre had not advised either aircraft of the other’s presence, but that had been normal practice in 1965. IFR aircraft in the US and Australia are now notified of each other’s presence. In addition, ADS-B acts a further warning system of aircraft so equipped. And Australian-registered air transport aircraft with more than 19 seats are required to have an advanced Traffic Collision Avoidance System (TCAS II) fitted, which goes one step further than ADS-B by predicting the flight path of nearby aircraft, based on their transponder data, and alerting the crew if it detects a conflict. The Carmel collision, one of 4 between 1965 and 1969 in the US, demonstrated why these measures and systems were necessary. The bullet-like closing speeds of jet aircraft were becoming too much for human eyes and reactions. In the 52 years since 1970, there have been 3 mid-air collisions involving airliners in the US.

Flight 853 is as clear-cut an example as exists of the difference a trained and capable cabin crew can make

What remains

There are several salient lessons from the unwelcome meeting of metal. As a concept, unalerted see-and-avoid had been insufficient to keep both aircraft safe. Alerted see-and-avoid, using radio calls, is 8 times more effective. Perhaps the phrase needs to be speak, see, and avoid.

Second, the crew never gave up. Like the crew of United Airlines flight 232 in 1989, the pilots of GOL flight 1907 in 2006 and possibly hundreds of others whose last efforts were never recorded, they kept working the problem until the last moment.

And flight 853 is as clear-cut an example as exists of the difference a trained and capable cabin crew can make. Had unbelted passengers been in the rear of the cabin at impact, the death toll would certainly have been higher.

Emile Greenway recovered from his injuries and went on to become a DC-9 captain with Eastern Airlines, retiring in 1989. On every flight he captained, he carried a pocket knife, for cutting seat belts.

Patricia Skarada never flew on duty again, although this was only indirectly due to the collision. During her long recovery, back at her parents’ house, her cousin set up a date for her with the man who would become her husband. Marriage automatically terminated her employment.

What sticks with me is not so much the crash itself, it’s the people I saw with the injuries.

‘I came through and I have to say I was pleased with myself,’ she says. ‘But there’s another part. There’s a guilty feeling too because 4 people died. Why couldn’t I help them too? That plays on your mind. What sticks with me is not so much the crash itself, it’s the people I saw with the injuries. Their faces flash back and trouble me.’

Love and family life nourished her, but she kept a secret from her children. They never knew about the crash and how their mother had helped save 50 people, until a day in 2017 when her grandchildren found a Federal Aviation Administration medal with her name on it, stored out of sight in the spare bedroom.

A landmark accident that showed how visual illusions can take us down a dangerous path. The positive take-aways are numerous but showcased is the crew’s devotion to duty and being proficient and ready to perform. They did indeed hear the bell and answered the call. Working the problem up to the final moments is so important; finding a way to survive and getting the airplane soon the ground. Bob Hoover said that when faced with challenges like the ones written about here, “Fly the airplane until the last piece falls off!” Thanks for a well written piece that remembers and pays tribute to the crew of Eastern 853.