‘Into the woods, but not too long: The skies are strange, the winds are strong.’ – Stephen Sondheim, 1986

American Airlines flight 1572

McDonnell Douglas MD-83, N566AA

Bradley International Airport, East Granby, Connecticut, US

0055, Sunday 12 November 1995

A common confession among airline pilots, is how they don’t actually do any work – they just get paid to fly. For these happy souls the intense study, testing and responsibility of the profession are all just part of the fun. On a traffic-free visual departure into smooth and sunny skies after several days of rest and relaxation, this disguised boast seems self-evident. It’s less of a truism on a dark and rainy night in a northern hemisphere November.

American Airlines flight 1572 pushed back from Chicago O’Hare Airport at 2305 on the evening of 11 November 1995 – about 2 hours late. The weather systems that often disrupt the complex daily ballet of airline movements in North America had made their presence felt, and the flight had been held to allow passengers on delayed connections to board. The crew used the time to further review the weather at their destination, Bradley Airport, in the state of Connecticut, near New York City. It was getting worse but was within limits.

After take-off, the aircraft’s automatic communications and recording system (ACARS) displayed information from American Airlines dispatch about conditions at Bradley. At the bottom of this all-capital letters message on the central pedestal screen lurked an acronym, PRESFR, which stood for pressure falling rapidly.

Rough ride

Flying at night: I don’t like it worth a (expletive) – CVR recording 17 minutes before impact

The pilots were aware the approach would be challenging but within limits. Before leaving cruise altitude, they had already briefed the cabin crew to finish meal service early and prepare for a bumpy approach.

On descent through 10,000 feet, the captain and first officer entered and cross-checked the QFE setting of 29.23 (990 hPa) into the left and right altimeters, according to American Airlines’ unusual procedure. This was to calibrate them to read zero feet at touchdown. For reasons never determined, the first officer entered an incorrect QNH (altimeter reading height above mean sea level) reading into the standby altimeter; there had been 3 readings available, from ACARS messages and Bradley’s ATIS. This caused it to read about 70 feet high but, as the crew were using the main altimeters on approach, this was not a significant factor in what was to occur.

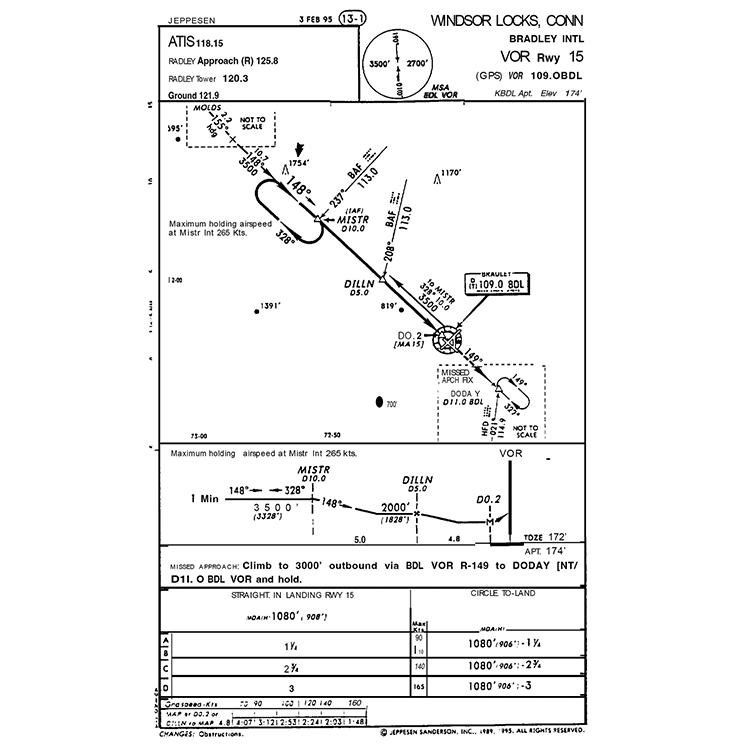

At 0043 Bradley Approach cleared a descent to 4,000 feet, with the winds dictating an approach to runway 15 which did not have a glideslope and would require a non-precision approach. The approach controller mentioned winds from 170 degrees at 29 knots gusting to 39 knots but did not offer any current information on pressure, and the crew did not ask for it.

The tower closed soon after this broadcast, because of a storm which was driving water through a window frame in the building where it formed a potential hazard around electrical equipment. A supervisor stayed behind to offer informal assistance to landing aircraft.

At 3,500 feet the MD-83 intercepted the 10-mile DME fix at the waypoint MISTR, 15 miles from the runway threshold. The approach was vertically stable at this point but strong sidewinds were overpowering the autopilot’s VOR capture mode. The captain switched to heading select mode to recapture the ILS. The aircraft overshot the localiser in the other direction but had levelled off at 2,000 feet by the time it passed slightly south of the final approach fix at DILLN, 5 miles from the threshold. All this took place in turbulence and heavy rain.

Dive and drive

The crew were flying the non-precision approach as though descending a giant invisible staircase towards the runway using a technique colloquially known as dive and drive. American Airlines encouraged an alternative continuous descent profile for non-precision approaches, but no continuous descent profile was available for Bradley runway 15. It had been removed after a ridge 2.5 nm from the runway threshold had triggered GPWS warnings in aircraft using it.

At DILLN the crew set 3,000 feet in the flight guidance control panel. In case of a missed approach, the aircraft would automatically climb to this height. But there was a trade-off. With this setting in place, it would no longer level off at the minimum descent altitude (MDA) of 908 feet above the runway (1080 feet AMSL). The crew would have to do this manually and monitor their altitude.

Bradley’s MDA was unusually high, over 700 feet above the runway. This was to give clearance from the ridge northwest of runway 15. It also meant the first officer’s stipulated ‘100 above’ and ‘1,000 feet’ callouts would be simultaneous.

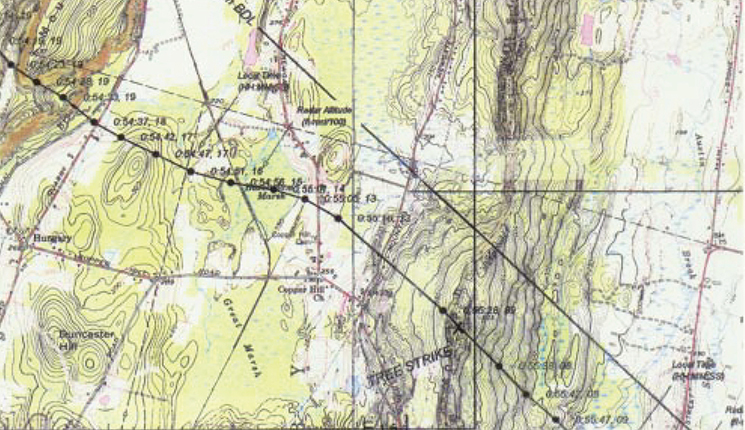

At 00:54:22, the captain asked the first officer to ‘give me a thousand down’, for a 1,000-feet-per-minute descent rate.

At 00:55:06, the first officer said, ‘There’s a thousand feet … cleared to land.’ Followed 5 seconds later by, ‘… now nine hundred and eight is your uh …’ The captain replied, ‘right.’

The first officer told investigators the aircraft was ‘at the base of the clouds’ and he had begun looking through the windscreen for the field. He looked back at his altimeter and saw that the aircraft was descending below MDA. After pausing briefly while the aircraft flew through turbulence, at 00:55:26 the first officer said, ‘You’re going below your … ‘

Before the sentence was complete, the captain pushed the altitude hold button for the autopilot. Even so, a plaintive ‘sink rate!’ warning sounded before an impact 4 seconds later.

Desperate measures

The aircraft had hit trees on top of the ridge 2.5 nm from the threshold.

Amid a clamour of beeps, horns and synthetic voices, the captain said ‘go!’ 2 seconds after the first impact and firewalled the throttles. The crew acted with seamless teamwork as the first officer retracted the landing gear and raised the flaps to 15 degrees at the captain’s command.

The aircraft had hit trees on top of the ridge 2.5 nm from the threshold.

Ten seconds after impact, the captain said, ‘Left motor’s failed’ just as the first officer said, ‘There’s the runway straight ahead.’ About this time, the right engine began to fail.

The captain asked the first officer to relay a message to the tower: ‘Tell ’em we’re going down.’

The first officer asked if the captain wanted the gear lowered again. The captain agreed – ‘Throw it down!’ – as the ground proximity warning system intoned, ‘Sink rate!’ repeating this mantra 7 times.

‘You’re going to make it,’ the first officer said.

At the first officer’s suggestion, the pilots began a discussion about flap settings, which lasted 22 seconds and culminated in the captain saying, ‘Flaps, flaps 40, all the way down.’ This created an effect well known to every student pilot: ballooning. The aircraft gained height and lost speed, and the combination of these brought it almost to the runway threshold. It clipped a tree, destroyed the ILS for runway 33 and rolled onto the reciprocal runway 15.

‘God bless you, you made it,’ the first officer said.

There was one slight injury among the 78 passengers and crew, although the aircraft required $US9 million of repairs.

Investigation

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determined the probable cause of the accident was the flight crew’s failure to maintain the required minimum descent altitude until the required visual references identifiable with the runway were in sight. The first officer looking for the runway instead of monitoring altitude as MDA approached had contributed to the aircraft going too low.

Contributing factors were the failure of the Bradley approach controller to give the pilots a current QFE altimeter setting, and their failure to ask for a more current setting.

The NTSB concluded if the controller had issued the current QFE altimeter setting on initial contact, the aircraft would most likely have been 40 feet higher than it was when it struck the trees. This might have been enough for it to have missed them.

But the crew had allowed the aircraft to descend about 309 feet below the indicated MDA for the instrument approach, the NTSB found. The weather at the time of the accident had not been severe enough to cause the aircraft to deviate below the MDA and did not contribute to the accident, the NTSB found. In particular, the flight data recorder yielded no evidence of strong downdrafts.

But in its analysis of events between tree strike and landing, the NTSB had high praise for the crew.

‘The Safety Board concludes that the excellent crew resource management and flight skills that the flight crew used … were directly responsible for limiting the number of injured passengers to one individual,’ the report said.

There was a later postscript. Writing on social media in 2024, Robert Benzon, one of the NTSB investigators of the crash said, ‘I and the other pilots on my NTSB team wondered if we could have done as well as this crew did in a similar situation.’

But the crew had allowed the aircraft to descend about 309 feet below the indicated MDA for the instrument approach.

30 years on

Controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) crashes were a depressingly regular feature of air transport in 1995. Such disasters had already occurred that year in Taiwan and Haiti, and before year’s end American Airlines flight 985 would crash into a mountain ridge in Colombia.

Dive and drive was a technique first developed for the smaller piston-engine aircraft of the 1940s and ’50s. But the higher speed, inertia and slower throttle response of much heavier jet aircraft made it easier for a brief lapse to lead to a dangerous loss of altitude. Few airline pilots of this era would have been able to say, hand on heart that they had never inadvertently ‘busted a minimum’ on a stepped non-precision approach.

Research in 2007 by the Flight Safety Foundation’s approach and landing accident reduction taskforce found more than half of accidents and incidents involving CFIT occurred during step-down non-precision approaches. Other data showed non-precision approaches to be more than 5 times as hazardous as vertically guided precision approaches.

Dive and drive has been consigned to history in air transport, with a corresponding reduction in airliner CFIT crashes. Global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) with ground or satellite-based augmentation enable performance-based navigation; this allows continuous-descent satellite-guided approaches to be flown, even at airports that have no ground-based instrument landing systems. Approaches with vertical guidance are a less precise version (than ILS) of this concept, using unaugmented GNSS, but even these are safer than diving and driving.

From 2028 the Southern Positioning Augmentation Network (SouthPAN) satellite-based augmentation system (SBAS) will enable vertically guided instrument approach operations, including localiser performance with vertical guidance (LPV), to most aerodromes in Australia.

More than technology has evolved. CASA Senior Standards Officer and former airline captain Ian Woods says adherence to standard operating procedures has become more consistent since 1995. ‘Procedures are more thoroughly nailed down now,’ he says. ‘When I went from Trans Australia Airlines to Qantas, the procedures for transition from IFR to visual was distinctly different between carriers. You wouldn’t find that now.’

The humbling and lasting lesson of flight 1572’s wild ride is that the best and the worst lurks in all of us.

But human performance is the same in 2025 as it was in 1995 – inherently variable. The humbling and lasting lesson of flight 1572’s wild ride is that the best and the worst lurks in all of us. Adherence to checklists and standard operating procedures do not replace skill, teamwork and heroic improvisation but they can prevent the situations where these admirable qualities are required.