by Thomas P. Turner

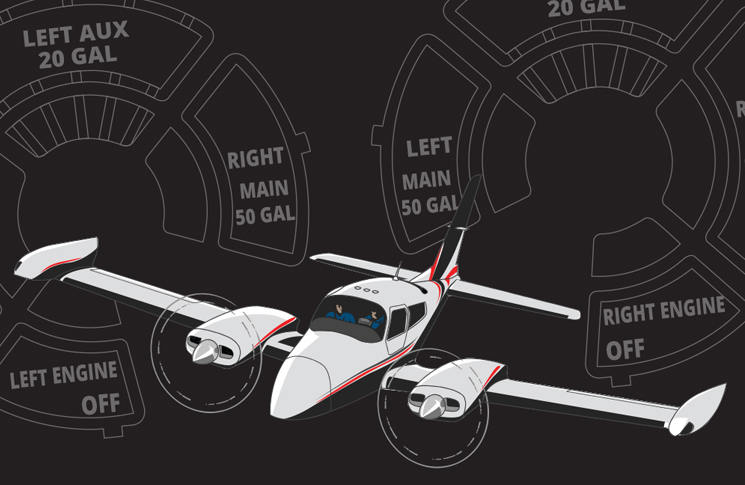

Fuel starvation (running the selected tank of fuel dry while other tanks still have fuel on board) can result from any of several scenarios:

- The pilot does not plan to have adequate fuel to reach destination on either tank independently, and does not properly time the switch between tanks.

- The pilot does not confirm fuel level through all means necessary before flight, and assumes the tank has more fuel on take-off than it actually does.

- Wind reduces ground speed below what the pilot planned, and the pilot does not recalculate fuel requirements while en route.

- The pilot attempts landing with an auxiliary fuel tank selected, which is against the recommendation of virtually all aircraft manufacturers and STC holders.

- During tank selection the fuel selector does not go firmly into the tank detent, cutting off fuel flow.

- The pilot does not manage power and fuel flow in the manner they planned, resulting in higher fuel flow than expected.

- Fuel siphons from a tank in flight and it no longer contains the amount of fuel the pilot thought it does.

Fuel exhaustion (running out completely) comes from insufficient or improper pre-flight planning, not thoroughly confirming fuel on board before take-off, or not monitoring the actual versus expected fuel burn over distance in flight.

Suggestions for fuel system management

Preflight: Before you board the aircraft, be able to answer four questions

- How much fuel is on board the aeroplane?

- How much fuel will you burn before each of several en-route checkpoints?

- How much fuel will it take to get to your destination under expected conditions?

- How much fuel will be remaining in the fuel tank you’ll have selected for landing when you touch down?

Fuel on board: Knowing how much fuel is aboard isn’t as easy as it may sound. For several years another pilot and I flew a pair of Beech Barons. It was difficult sometimes to determine how much fuel was on board before a flight when the other pilot had flown it last time; we couldn’t routinely fill the tanks after a flight because of possible weight limitations on the next trip. To be safe before flight we each confirmed fuel in seven different ways:

- Visual inspection of the fuel tanks through fuel filler ports. In Barons, because of wing dihedral if there’s less than about ¾ fuel on board you cannot see any fuel in the tanks through the filler port.

- Sight gauges, mechanical fuel indicators mounted on top of the wings.

- Cockpit fuel gauges.

- A fuel totaliser showing fuel remaining on board.

- A written record of the Hobbs (flight time meter) time when the aeroplane was last fuelled, and the amount of fuel added.

- Checking fuel vents and overflow ports, and the floor of the hangar or ramp under the aeroplane, for signs of fuel leaks.

- Fuel receipts … although these are the least reliable indicators.

When I arrived for a flight I checked each of these sources. If I could not positively determine the amount of fuel on board by multiple means, or if any two were different enough that it didn’t make sense, I topped the tanks before departure regardless of the length of the planned flight. If weight and balance was an issue I’d add enough fuel to make the trip regardless of what was already in the tanks (most of our flights were only about an hour); until I had some visual confirmation that I had a safe fuel level with reserves (written fuel log plus added fuel, for instance; or until I had a positive indication on the sight gauges) while remaining within weight and balance limits.

Fuel to destination: Use aircraft performance charts, expected winds, and your own experience with fuel burn to estimate the fuel you’ll use to get to your destination. If you’re flying near the limit of your aeroplane’s fuelled range, schedule tank switching and estimate fuel remaining at various decision points along the way. This helps you better monitor fuel flows and recalculate fuel remaining at destination while you have time to do something about it if your reserves become too low.

Before take-off: In aeroplanes with independently selectable fuel tanks, I start the engine on one and taxi on that tank. By the time I get to the run-up pad, I know I’ve got good, usable fuel available in the selected tank. I then switch tanks and perform the engine run-up on the other main tank. Now I know the engine can support relatively high power with good, usable fuel in that tank as well. Regardless, I always take off on the tank used for engine run-up. Do not switch tanks just before takeoff; there are many cases when an engine quits immediately after lift-off because the pilot did not get the fuel selector in the detent.

If you have auxiliary fuel tanks and you’re planning to use them, step through the auxiliary tank positions after reaching the run-up area but before selecting a main tank for run-up and takeoff. Auxiliary fuel tanks are usually prohibited from use during take-off and landing—and the accident record shows this limitation is very real.

Take-off and climb: Once you’ve established cruise climb, glance out at the fuel filler caps or vents, if you can see them from the cockpit. Look for any sign of fuel streaming or venting. If you see any misting there or from the wing’s trailing edge, land right away and reconfirm the fuel remaining by multiple means.

Cruise: Cruise flight is where individual preferences make fuel strategies very personal. There are a few commonalities to consider, however:

- Lean the fuel/air mixture to obtain the power and fuel burn rate you planned for the flight.

- Use a GPS reminder, a timer or some other memory jogger to prompt tank changes, if required. Manage your fuel burn to keep the left/right weight balanced, and to ensure you have enough fuel remaining for descent, approach and (if needed) a missed approach and climb back to altitude. A simple method is to switch from one tank to the other every 30 minutes.

- Whenever possible, make fuel tank changes when within gliding distance of an airport, just in case your tank change causes a power interruption. Any number of things—a blocked fuel vent, siphoned fuel, incorrectly calculated fuel state, ice in the tank—can make the engine starve for fuel. You need to have altitude to restart on another tank, and a place to land if for some reason changing tanks does not relight the engine.

- Switching fuel tanks is a three-part process: 1) move the tank selector, 2) make certain it is firmly in the new position, and 3) leave your hand on the selector handle for several seconds while watching the fuel flow or pressure gauge, if the aeroplane is so equipped. If flow or exhaust gas temperature (EGT) begins to drop, switch back to the previously selected tank to keep the engine running. Confirm you have fuel in the tank you’ve tried to select, then again attempt to switch tanks if it makes sense to do so.

- Don’t run a tank completely dry. Although in theory an engine that quits when a tank runs dry will immediately restart when you switch to a tank containing fuel, several times each year we read of cases where this doesn’t happen as expected. Changing tanks when there’s five to 15 minutes’ fuel remaining in the tank won’t substantially decrease range. If draining a tank dry makes the difference in whether you make it to your destination, you need to reconsider your overall risk management philosophy.

More considerations for cruise flight fuel strategy:

- As you pass checkpoints or GPS distances remaining, check actual fuel burn against anticipated. Recalculate fuel remaining at destination if your actual burn exceeds what you predicted to that point.

- As you did during climb, glance out at the fuel caps or fuel vents occasionally if they’re visible from the cockpit, and the wing or structure behind caps and ports to discover if fuel is siphoning overboard in the slipstream. Land if you note any leaks.

- Follow precise mixture leaning procedures to get the best fuel flow for your flight, whether it be a fast trip, an endurance run, or some compromise between the two.

- Compare fuel gauges and totalisers to your calculations and a clock in a regular fuel crosscheck. If the fuel gauges read lower than expected, land and reconfirm the fuel on board.

- Recompute reserves often enough you can easily land early if needed.

- Use an alarm or timer to remind you when to switch fuel tanks, if needed.

- Reduce power and cruise slower for longer endurance, if needed.

- Don’t hope the ground speed will improve, or think you’ll ‘make it up in the descent.’ Fuel exhaustion happens within a mile or two of the intended destination when the pilot thinks they have enough to make it.

- Make the decision early to land for fuel if you cannot work out what fuel remains, or if your computed reserve at destination slips below your minimums. ‘I might have been able to make it nonstop’ is a much more desirable post-flight reflection than ‘I almost made it’.

Descent, approach, landing and missed approach: Make your final fuel tank selection at the top-of-descent (just before beginning descent from cruise). Pick a tank with adequate fuel for descent, landing, go-around or missed approach, and climb to a safe altitude without further selections. If you can’t plan your flight to do this, in my opinion you have not adequately planned your flight and en route fuel stops.

Fuel management is not as simple as it seems. Maybe that’s why fuel mismanagement crashes are so common. You need to develop your fuel strategy before taking off, and monitor fuel closely in flight.

[…] reminder of the importance of fuel management, which Flight Safety Australia has written about in 2016 and […]

[…] a Flight Safety Australia article in 2016, Thomas P.Turner suggests pre-flight strategies, including for aircraft where pre-flight visual inspection of fuel levels may be impractical. […]

[…] Fuel management is a perennial cause of accidents and incidents, particularly in general aviation. Flight Safety Australia has covered the topic regularly, most recently in 2016. […]

Thank you for sharing some tips! I can use this to my fuel works.