It was the year of the final moon landing and the first flight of an Airbus. Transistor radios and stereograms were playing John Lennon’s Imagine and Don McLean’s American Pie. Cinemas were showing The Godfather. Terrorists massacred Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics. It was also the most dangerous year to fly on an airliner, as measured by deaths: around the world 2373 people were killed in airline crashes during 1972.

There were 72 airliner crashes in 1972 (defined by the Aviation Safety Network as hull loss of a 14 seat or greater aircraft), which was fewer than the ASN’s worst year by crash numbers, 1948, when 99 airliners crashed. But due to the larger size of aircraft in 1972, those 72 crashes killed many more people.

The year was a week old when a Spanish airliner flew into a mountaintop, reportedly while its crew were discussing football with ATC. Eight days before year’s end, a similar accident happened in Norway, this time with the crew and ATC talking about Christmas. Yet it was not to be the last major crash of the year. On 28 December a Lockheed L1011 Tristar descended into a swamp near Miami Airport, in the US, killing 101 passengers and crew.

Crashes were happening for age-old reasons, chiefly controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) and loss of control in flight (LOC), but to new and larger aircraft.

The destruction of an Ilyushin 162 in October 1972 became the world’s most deadly aircraft crash, killing all 174 on board. But this grim record was eclipsed the following January by a Boeing 707 crash that killed 176 people. As of 2016, the loss of the Ilyushin, Aeroflot flight SU217, (see table) is merely the 44th most deadly airliner crash.

Australia had a clean airline safety record in 1972. Flight International in an airline safety review published on 17 May 1973 had some interesting observations as to why.

‘Air safety regulation—toughly enforced—is led by professionals who have been in the job for many years. Australia’s safety record may also owe something to its long-established system of mandatory defect and incident reporting with strict follow-up action, and to full publication of financial information,’ Flight International noted, adding that ‘Australia has been described as a “police state” in its air safety regulation and enforcement.’

In another life—the standards of the time

CASA flight simulation team leader, John Frearson, was a 21-year-old junior first officer in 1972, flying Fokker F27s for TAA.

‘Even if you were there, it’s hard to go back now and put yourself into that world,’ he says.

‘The prevailing attitude to accidents was somewhere between resignation and determination,’ Frearson says.

‘It wasn’t acceptance of the inevitability of fate it was more “these things are going to happen,’’ combined with a desire to make sure they didn’t happen to us.

‘TAA did live up to its “Schedule is important but safety is most important” founding ethic.’

Frearson cautions against attributing too much significance to the record of any one year but says the early 1970s were a transition period in aviation with new wide-bodied aircraft entering service but with specific operating techniques and general safety culture evolving more slowly.

The crash of the Tristar, Eastern Airlines flight 401, on 28 December 1972, is a case in point, the first fatal crash of a wide-body airliner, Frearson says. ‘It was among the crashes that began the impetus towards crew resource management (CRM). I’m hesitant to say it was the one, because there were plenty of similar crashes but after Eastern 401 the concept of task allocation came in.’

‘As the cockpit management issue developed into CRM after subsequent crashes, such as the loss of United Airlines flight 173 in Portland (US), airlines began their own CRM training programs. There were a number of mnemonics guiding crews in active CRM—the one we used was SADIE: share, analyse, decide, implement, evaluate.’

Frearson notes how common technologies today have eliminated the killers of the early ‘70s, which were CFIT and to a lesser extent mid-air collisions. In 1972, Canadian engineer Don Bateman was already working at Honeywell on a ground proximity warning system (GPWS), which was made mandatory for airliners in the US in December 1975. (Bateman ‘probably saved more lives than any single person in the history of aviation,’ according to the Flight Safety Foundation.)

Similarly, traffic collision and avoidance systems (TCAS) now largely eliminate mid-air collisions. TCAS was made a requirement in the US in the 1980s after the collision of a Piper Archer and McDonnell Douglas DC-9 in 1986.

Human factors was a novel and vaguely understood concept. When Frearson was a cadet pilot, his girlfriend, later his wife, bought him a book, The Human Factor in Aircraft Accidents. ‘That was the first time I’d heard the term,’ he says.

‘It’s a concept that could have saved many lives in 1972,’ he says. ‘In how many of those accidents was someone either in the cockpit, or in a previous cockpit, with concerns that such an accident might happen? Those are the accidents where the whole concept of CRM comes into play—people speaking up early.’

Airbus A330 check and training captain pilot, Steve Wright, began his aviation career in 1972 with ab initio training in a RAAF Winjeel. Individual commitment to safety was excellent, he remembers, but understanding of the role of organisations in creating a climate of safety was limited. ‘This was very much the time of pilot error. The concepts of the organisational accident and James Reason’s Swiss cheese model just were not on the books,’ he says.

Frearson says the foundations of what are now called safety management systems (SMS) were starting to appear. ‘The idea was taking root that you were required to not only learn from your own organisation’s incidents but from other people’s as well. There was always a copy of Flight International in the crew room and the company had a Roneoed (spirit duplicator printed) safety magazine that referred to international accidents.’

One of those Roneoed reports stuck in Frearson’s mind over his career, and inhibited him from being tempted into short cuts. It was the 1973 CFIT crash of Texas International flight 655, a Convair 600 that diverted around a storm into a mountainous area.

‘The first officer said, “Minimum en route altitude here is forty-four hun … “ he never finished the sentence,’ Frearson recalls.

Over the following decades, Frearson saw gradual but unceasing evolution and elaboration in every aspect of aviation safety. ‘For example, before a 1976 accident involving windshear on final you would have been failed on a check ride if you firewalled the throttles on missed approach, and you would have failed the sim check for getting the stick shaker on a missed approach,’ he says.

‘But after that accident it was determined that had the crew firewalled the throttles and flown out at the stick shaker angle of attack they might have survived. So we changed the procedure.’

Frearson saw standardisation become the norm, as airlines got bigger and it became impossible to know all the pilots. ‘That meant training had to be standardised and SOPs had to be written so a below average pilot having a below average day would still survive. The result was you were relying less on skill and sense.’

Wright emphasises how pilots of the time had a high workload and little help from automation. ‘Airline flying was all about tracking VOR radials, so the crew would be continually selecting different modes on the autopilot. In terminal areas you were working with radar and a high pilot workload to intercept and track navaids.

‘Hands-on flying was mostly done to a pretty high level, in every sense. The autopilot capability down near the ground just wasn’t there-—you wouldn’t routinely engage the autopilot until 9000 ft, and would disconnect at 2000 ft or higher on approach. So it was quite a high workload between the two front-row crewmembers, manually tuning navaids, redialling radials—there was no autotuning until the Boeing 767.’

Engine monitoring was distinctly old-fashioned, Wright remembers. ‘The flight engineer had an A3-sized log with carbon paper and that’s how engine parameters were captured—fuel burn, oil use, etc. Eventually these would find their way back to the engineering department, where someone, somewhere would enter them into a database.’

That was then, what now?

The paradox is that by the standards of the decade that preceded it, 1972 was a relatively safe year for passenger aviation. Many people died, but as a proportion of those who flew, there were fewer deaths than a decade earlier. In 1959, there had been 40 deaths for every million scheduled passenger flight departures. To put it another way, when a passenger boarded an airliner they had a 1 in 25,000 chance of being involved in a fatal crash (but not necessarily killed). By the end of the ‘60s, there were fewer than two deaths per million flights, or a 1 in 500,000 chance of being in a fatal crash on any flight.

As of 2015, the chance of being involved in a fatal crash on a scheduled passenger flight has fallen to 1 in 29 million. Meanwhile, air travel has increased nearly tenfold. Interpolating from World Bank figures, about 360 million people flew on scheduled flights in 1972. For 2015, the corresponding figure was 3.4 billion. A third of that traffic growth has taken place since 2010.

In 1972, 2373 airline travellers died. In 2015, it was 560, a quarter as many killed despite the growth in air travel. But safety analysts caution of the potential threats behind the headline figures.

Frearson and Wright both nominate complacency as a growing hazard in modern skies.

Frearson says, ‘We’re seeing fewer accidents these days but they are different, more insidious, often involving a shocking lack or loss of basic flying skills. In accidents like Asiana at San Francisco, or Turkish flight 1951 at Amsterdam, we see each pilot assuming the other knows what they’re doing and they are passively going along. It’s ops normal, except the angel of death is tapping on the windscreen.

‘The result is we have accidents in highly complex airliners where pilots have failed to do what a Tiger Moth pilot would do—push the throttle and fly out of the stall.’

Wright says some common factors to the Air France 447 crash in 2009 and the Eastern crash in Florida in 1972 show that often subtle lessons and lingering design flaws have not always been learned or understood.

‘They have some things in common—crews that did not, for various reasons, understand or perform the fundamental task of flying the aircraft. In both cases, there were aural alerts but we know that, from a psychological point of view, humans under high stress and workload lose their aural channel. You literally don’t hear the warnings.

‘In an era of automation and complexity we have to keep sight of the basics of flying, because they haven’t changed and we ignore them at our peril.’

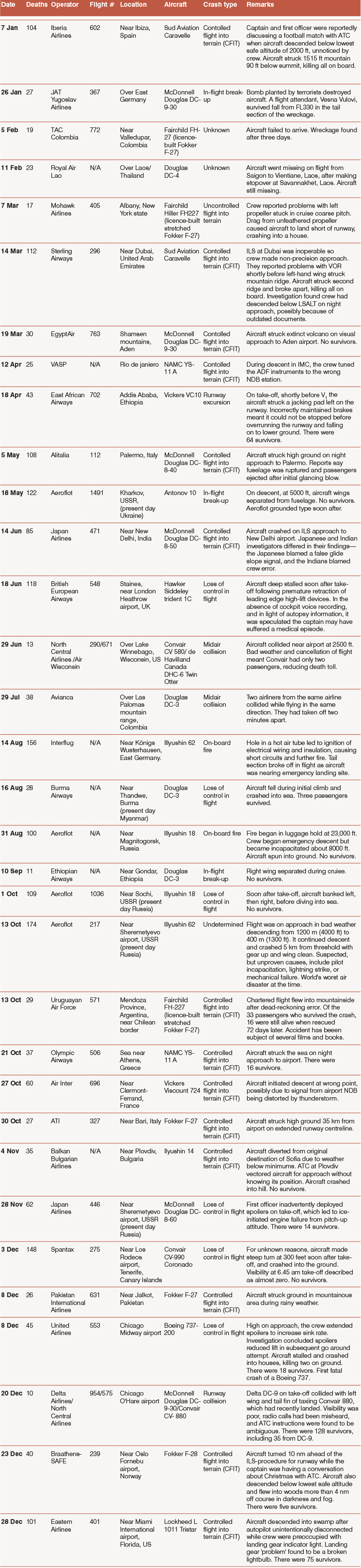

The year of flying dangerously: Selected passenger crashes of 1972

Wings of change

The Illyushin 62, was a mainstay of Soviet bloc airline transport in the 1970s. For a few months between 1972 and 1973, the type held the sad record for the world’s most deadly air crash.

Wide body types, such as the Boeing 747 and Lockheed Tristar, were entering widepsread service in 1972. Before year’s end, a Tristar was lost in a crash which focused attention on human factors in aviation. Its crew had not noticed a gradual night-time descent because they were concentrating on a broken light bulb. The precise reasons behind the loss of a Hawker Siddeley Trident near Heathrow airport, lower small picture, may never be known as it carried no cockpit voice recorder.

Excellent reading, only trouble is with all the fairy-tale stuff of CRM, HR dept’s, psych testing at interview & all the ground dwelling do gooders that now almost out number the pilots in a Co means zip! You can make a 100 airframes identical right down to the colour of the toilet paper but you will never make all pilots the same, simple fact is that human’s will continue to fly into fully serviceable mountains (yes said intentionally) in fully serviceable planes because we are fallible, we have a brain, the one organ we know virtually nothing about. Throw in commercialisation where money & scheduling now feature way ahead of safety (yes true but nobody admits it !) & poorly treated pilots all means plane crashes will feature in all forms of media ’till the next ice age!

I read with interest The Year of Living Dangerously – 1972, and it brought to mind another tragic year – 1956, and the in flight collision of a TWA L1049 and a United DC7 over the Grand Canyon.

That particular accident resulted in the development and fitment of rotating anti collision beacons. I recall being involved in the installation of some of them to the QANTAS L1049’s.

Regrettably ‘they’ didn’t stop aircraft flying into “Granite filled Clouds” as in the case of Alitalia I-DIWD in India and Air New Zealand ZK-NZD in Antarctica – both of which resulted in the loss of two of my LAME friends.

Barrington G Ogden LAME # 4701

– retired QF Line Stations LAME

– retired Dept of Aviation Snr A/Worthiness Surveyor

[…] The following graph shows aviation accidents between 1946 and 2018 and highlights how safe flying now is compared to previous years. The deadliest year for fatalities was in 1972 when there were 72 airline crashes resulting in 2373 fatalities. The ASN’s worst year by crash numbers was 1948, when 99 airliners crashed. But due to the larger size of aircraft in 1972, those 72 crashes killed many more people. Flight Safety Australia looked at some of the reasons why in ‘The year of flying dangerously: 1972’. […]