Exactly 100 years ago tomorrow two pioneers became the first people to experience an aviation-related malady that has since affected millions and remains a factor in aviation safety management to this day.

Pilot John Alcock and navigator Arthur Whitten Brown were having a hard time getting up in the mornings immediately after they made the first non-stop flight over the Atlantic Ocean. Twenty years before the invention of the jet engine, they became the first people in history to experience what is now called jet lag.

‘In our eastward flight of two thousand miles we had overtaken time, Brown wrote. ‘Our physical systems having accustomed themselves to habits regulated by the clocks of Newfoundland, we were reluctant to rise at 7 am; for subconsciousness suggested it was but 3.30 am.’

Brown noted that this difficulty of adjustment to the sudden change in time lasted several days. ‘Probably it will be experienced by all passengers travelling on the rapid trans ocean air services of the future…’

Brown was right; fatigue remains a factor in aviation safety 100 years later. This year CASA is implementing its response to an independent review that confirmed the need to modernise Australia’s fatigue rules for air operators and pilots.

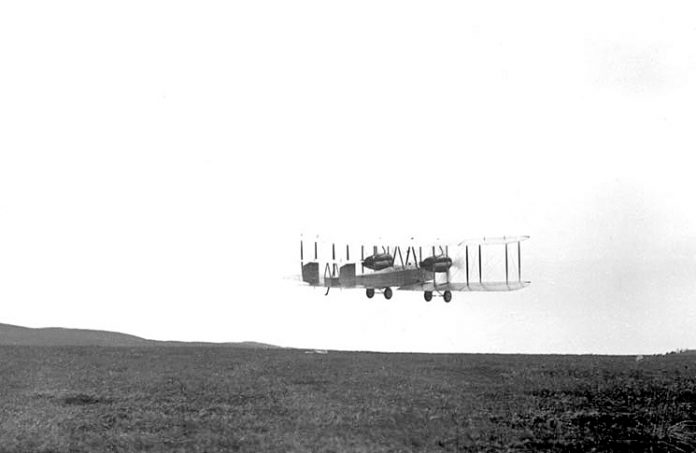

Alcock and Brown took off in the afternoon of 14 June 1919 from Lester’s Field, near St John’s on the Canadian island province of Newfoundland. A contemporary photograph shows the fuel-heavy aircraft barely airborne near the airfield. ‘Several times I held my breath, from fear that our undercarriage would hit a roof or a treetop. I am convinced that only Alcock’s clever piloting saved us from such an early disaster,’ Brown wrote.

Their flight was eventful, with an exhaust manifold breaking and subjecting the cockpit to a deafening roar, airframe icing, and on two occasions, loss of control. The Vimy was not equipped with ‘blind flying’ gyroscopic instruments; instead Alcock relied on longitudinal and lateral spirit levels.

Brown described how ‘about sunrise, 3.10am, to be exact,’ the Vimy had spun (or possibly spiral dived) from 4000 feet to under 100 feet.

‘We left the cloud as suddenly as we had entered it. We were now less than a hundred feet from the ocean. The sea-surface did not appear below the machine, but, owing to the wide angle as which we were tilted seemed to stand up level, sideways to us.’

Later, sleet jammed the ailerons and Brown was required to step out of the cockpit to wipe slush off a fuel gauge, an exercise he described as ‘very unpleasant,’ but which he repeated at ‘fairly frequent intervals’.

After just over 16 hours of flight they saw the Irish coast and lined up with what looked like a green field, near Clifden in the country’s rugged west.

From Brown’s description: ‘The machine sank gently, the wheels touched earth and began to run smoothly over the surface. Already I was indulging in the comforting sensation that the anxious flight had ended with a perfect landing. Then, so softly as not to be noticed at first, the front of the Vickers Vimy tilted forward, shook itself, and remained poised on a slant, with its fore-end buried in the ground, as if trying to stand on its head.’ The green field was an Irish bog.

After landing, fatigue overtook the two aviators. ‘I suddenly discovered an intense sleepiness, and could easily have let myself lose consciousness while standing upright’ Brown wrote, noting also his ‘lassitude of mind’.

An Irish journalist drove them (in a Ford Model T) to the nearest large town, Galway, with crowds of well-wishers gathering along their route. Interest in the race to cross the Atlantic was intense after the recent rescue of Australian pilot Harry Hawker. A civic reception was mercifully rescheduled into ‘a short and informal affair,’ and, after 40 hours awake, Alcock and Brown finally partook of the only sure remedy for fatigue – sleep.

No one has to remind us pilots what fatigue is or what effects it has on us, tell the AIRLINES who despite all the feel good crap they dream up to con/appease the authorities they still look at pilots as tools to abuse!

You take a day off due fatigue & yr name goes in the little black book the rostering Dept keep hidden away! The management know who the trouble makers are!!

It’s an insidious thing fatigue, some days there seems no ill effects, other days you are as flat as a pancake!

The sooner they invent pilotless planes & drones the better I reckon….cough cough!

And when it comes to so called regulatory reform the regulator ignores pilot input and science and sides with the employer every time.

Too true, remember CASA is made up of people from ex Airlines and other parts of the industry, lots of mates for mates, corruption is rife in the regulator!. Does everybody truly think that CASA employees dropped out of the sky from another planet uncorrupted? They are after all humans ( well using that word lightly) and subject to irrational self serving thinking! The Airlines are very powerful, without them there would be no CASA so fatigue management is in CASA’s best interest to make work, the Airline way!

My daughter worked as a flight attendant with a major Australian “low fare” airline. She was employed under a contract through a Melbourne labour hire company: $20/hr from sign on to sign off and $10/hr while the aircraft was moving. She had no job security and no sick or holiday pay. Her work hours were at the whim of the airline. One month she didn’t make enough to cover her car repayment. When she had SYD/PER/SYD overnight flights I’d pick her up at 7:30am after the flight because it was too dangerous for her to drive: she worked all day in a hairdressing salon (her reliable job!), then drove home to change into her uniform, then to the airport to work overnight on the flight. To highlight the callous attitude of the airline, a colleague died in a single vehicle accident after such a trip.

When I worked for one of the LLC’s I always felt sorry for the F/A’s, they where practically abused, work place bullying but ‘legally’, it was a disgrace to watch! That was one of the worst parts of the Airline industry that is ‘accepted’ as the norm! The F/A turnover was huge and for good reasons! My recommendation to passengers is to familiarise yourself with the Emergency procedures as you could very well be on your own in the real world!