The story of Australia’s first civilian turboprop crash shows how much investigation and analysis have evolved since the 1950s

By Robert Wilson

Three o’clock is either too early or too late for anything you want to do, the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre declared. With a broad view and 65 years of hindsight it’s easy to philosophise that 3 pm on Sunday 31 October 1954 might have been a good time for the crew of VH-TVA to take a tea break.

TVA was an early production Vickers Viscount, the first of its type in Australia. It had been in the country for 18 days, flying a few passenger services, but was mostly being used for crew training. TAA was the fourth airline in the world to order the pressurised four-engine turboprop at the unprecedented price of A£217,000 (A$434,000) per aircraft.

That Sunday it had been earning its keep on training flights between Mangalore in rural Victoria and Essendon, then Melbourne’s primary airport. By 3 pm it had completed a circuit in which its outer right engine had been shut down. After landing it turned on the runway for a three-engine take-off on Mangalore’s runway 22.

Accident reports in the 1950s had no inhibition about using people’s names, probably because Australian civil aviation was such a small world that everybody knew everybody else anyway, by either name, face or reputation. It’s therefore on the public record that the pilot in command was Captain D. K. Macdonald, occupying the right-hand seat, with pilot under training R. D. H. Fisher in the left-hand seat. Two other pilots and an engineer were observing from the rear of the cockpit and three others, including a company engineer and his seven-year-old son, were seated in the cabin.

After turning on the runway, Macdonald and Fisher made a pre-take-off cockpit check then opened the number 2 and 3 engines to take-off power. Fisher released the Viscount’s distinctive yoke-mounted brakes and, as the aircraft moved forward, gradually advanced the No. 1 throttle for the outer-left engine. The time was about 3.05 pm. The skull-cracking shriek of Rolls-Royce Dart turboprops would have filled the sky and shaken the silent sabbath.

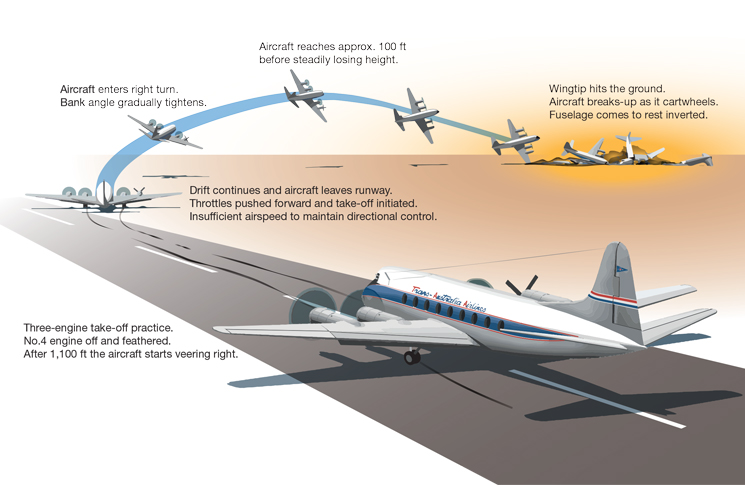

From the report: ‘When the aircraft had travelled some distance a swing to the right developed but this was corrected by the use of nosewheel steering. However, this was followed almost immediately by another more severe swing to the right and the aircraft left the runway and became airborne at a speed below the minimum control speed.’

The Viscount took off with an initially gentle climbing turn to the right. Witnesses saw the turn steepen and, after climbing to about 100 feet, the aircraft steadily lost height until the right wingtip struck the ground. Just before ground impact, one of the observing pilots, George McDougall, moved into the cabin. Macdonald, Fisher and observing pilot John Nickels were killed. Four others were injured to varying degrees and the engineer’s son escaped unscathed.

McDougall told the inquiry that as the aircraft left the runway, Macdonald had pushed the throttles fully open and pulled the aircraft into the air at an airspeed between 85 and 90 knots.

His account was confirmed by calculating the speed the aircraft would have reached with normal acceleration in a three-engine take-off up to the point where it left the runway. Further calculations showed it could not have been controlled directionally after it left the ground, if three engines were developing full power at speeds below 96 knots.

The report’s judgement was ruthless, if superficial, blaming the pilot almost with a sense of relish, but saying little about the aircraft and nothing on the training regime. ‘An error of judgement was committed by Captain Macdonald and the accident resulted,’ it said. ‘Macdonald may have been influenced in this decision by his experience on other aircraft recently flown by him, the minimum control speeds of which are lower than that of the Viscount.’

‘It is felt that in an emergency such as faced Macdonald, he would be inclined to react automatically under the influence of his predominant experience in the DC-4, overlooking the particular characteristics of the Viscount of which he was comparatively inexperienced,’ it opined, without any attempt to find out why, with such limited experience, he was a training captain and making a three-engine take-off. Macdonald had 3158 hours on the DC-4 and 21.5 hours in command of the Viscount and had been made a training captain after just more than 10 hours on the type.

The report discussed nosewheel steering and pointed out how the responses of the Viscount’s turboprops were different to those of piston engines. ‘The proportionate increase in power obtained in the final stage of throttle opening is much greater with the turboengine than with the piston-engine. Also, the response to throttle opening in the turboengine is slower than in the piston-engine.’

The survivor’s account

The seven-year-old boy was Roger Clifford, now aged 72. He was with his father, a TAA engineer, who had flown on the aircraft on its delivery flight from England. He remembers the final take-off as normal with no noticeable swing and recalls how his father and another engineer chatted throughout the manoeuvre.

‘The first inference that something was wrong was when I heard my father say, “we’re going in”,’ Clifford remembers.

‘I have a very strong recollection of looking down the port [left] wing at the ground, which meant port wing low while the report described the starboard wing hitting first.

‘As my father described it, one wing went low, hit the ground and broke off. The other wing then dropped, struck the ground, following which the aircraft pivoted on that wing and its nose. At some time during that, the tail section, in which we were sitting, separated and somersaulted, finishing upside down partly on, and partly adjacent to, the nose section.’

The moment of impact is a blank to him, with memory resuming soon after.

‘We were hanging upside down in our seat belts and my father got himself out, then got me out of the seat,’ he says. ‘In that model of the Viscount every window was an emergency exit and I have a recollection of being passed out and down to a man on the ground.

‘My father took me away from the crash, sat me on a fallen tree and told me stay there. I remember one of the aircraft wheels still rotating, whether from the take-off or from the crash I have no idea.’

His father, John, retained disturbing memories which were at odds with the official report. ‘I don’t recall—but my father did—that at least one of the crew members was alive after the crash,’ Clifford says. ‘When it crashed, an electrical fire broke out immediately behind the cockpit. Escape was not possible because of the fire at the rear and, although the cockpit side windows could be opened, two horizontal bars prevented egress.

‘That’s in direct contradiction to the report which says they were killed on impact. But after that crash, Vickers took those struts out of the Viscount, thus enabling the cockpit windows to be used as emergency exits.’

Other aspects of the aftermath were almost comic, Clifford remembers. ‘There were three seriously injured, who were taken to Melbourne in the same ambulance. But they can’t have been that badly injured because the ambulance stopped at the Broadford Hotel and they went in for a beer, except for one, who had his beer brought out to him. I had to stay in the ambulance.’

His other memory of the day is sitting quietly in the hospital waiting room while a horde of journalists harassed the staff for access to the accident victims. ‘They never knew one of the survivors was right under their feet.’

Analysis: out of the cockpit, beyond the runway

If the accident report was to be written now, it would be a very different document, CASA senior standards officer Ken Alonso says.

Buried near the end of the 1955 report, as the seventh of its nine conclusions, is a sentence that adds to the tragedy: ‘Training in three-engine take-offs during pilot conversion on four-engine aircraft is not a requirement of the Department of Civil Aviation for endorsement of such types on pilot licences.’

In short, the deadly exercise had been unnecessary, but the report did not seek to find out why the crew had attempted it or if it was possible. Instead, it examined in as much detail as it could—without data from a cockpit voice recorder or flight data recorder—possible scenarios involving loss of nosewheel steering effectiveness. In the phrase of Professor Sidney Dekker, the accident report described was a ‘down-and-in, not up-and-out’ investigation. The difference is analogous to the difference between looking with a microscope and a wide-angle lens. Sometimes the microscope is appropriate, sometimes the wide view is necessary. Professor James Reason’s Swiss cheese analogy of accident cause shows us that accidents have both specific and general causal factors, which are ranked, as far as can be determined.

The report grasps some important specifics. ‘The comment about lag and the point at which the engines “bite” is particularly relevant,’ Alonso says. ‘It would appear to have taken them to the scene of the accident in this case.’

But it misses the significance of the Viscount’s considerable novelty, only hinting at it with the coined word ‘turboengines’. And the pilot’s mere 21.5 hours in command of what was not only a new type, but a new category of aircraft—a pressurised turboprop—is listed as just one more detail among many.

‘That amazes me,’ Alonso says. ‘These days airline operation is defined much more clearly, with more emphasis on training, checking, currency and recency.’

Alonso notes that high-fidelity flight simulators (as opposed to IFR Link trainers) were a new and uncommon technology then, but he adds that cardboard ‘paper tiger’ cockpit drill trainers had been in use since World War II. A rare three-engine take-off (as opposed to an engine failure on take-off) could and should have been drilled on one of these, he suggests, at least until the operator and its pilots had more familiarity with the Viscount.

He contrasts the report with one written 40 years later into the nosewheel-up landing of an Ansett Boeing 747 at Sydney Airport in 1994. ‘The Ansett 747 nosewheel collapse report was fairly cursory when it dealt with the events on the flight deck but went into significant depth about the systems approach and how the introduction of a new aircraft type and a new route had been pushed through.’

For Clifford, with all proper respect to the dead, the crash became, in the words of W.H. Auden, ‘a day when one did something slightly unusual’. He was feted for a few days at primary school and cured of nervousness by his father’s insistence that he fly again soon and often.

He was mentally robust enough to remain a confident and engaged passenger, despite a hard landing in a Hiller helicopter when he was about 15. ‘I’ve had several escapes in my life,’ the retired electrical engineer says, ‘but the two in aircraft have not resulted in a fear of flying.’

[…] our previous stories on the Lockheed Hudson, Vickers Viscount and MD-83 […]