The effects of years of organisational amnesia, imprecision and improvisation came to a head one terrible morning over Bass Strait

Boeing 707-368C, A20-103, ‘Windsor 380’

Sea near East Sale, Victoria

Tuesday 29 October 1991

A busy week, in a busy month, in a busy couple of years.

For Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Squadron Leader Mark Lewin, the morning’s training flight over south‑eastern Australia was just one of his many duties. Lewin was 33 Squadron’s only qualified flight instructor (QFI) which made him an exceptionally busy officer, even before the additional impact of a tanker upgrade program for the squadron’s Boeing 707s, which was taking aircraft out of service, preoccupying the squadron’s leaders and increasing the workload on their subordinates.

The rebuilding of Australian civil aviation after the pilots’ dispute of 1989 was exerting a constant drain on Air Force pilots, with the temptation of salaries and promotion in the airlines. Training of replacements was therefore a full-time role. To add to Lewin’s workload, some pilots were being posted to the squadron – and its large, complex aircraft – direct from pilot training course. There was a simulator, but it was at the Qantas Jet Base in central Sydney. Moreover, the ‘box’ was often unavailable, and even when it was free and working, its software had little fidelity in modelling exercises such as asymmetric flight.

Lewin and 2 students, Flight Lieutenants Tim Ellis and Mark Duncan, had been on the simulator the previous day. Now it was time to practise situations beyond the simulator’s capability. They took off in a Boeing 707 with callsign ‘Windsor 380’ at 1038 from RAAF Base Richmond northwest of Sydney, with a flight plan for instrument approaches and landings at Richmond, East Sale, Avalon and Canberra, and asymmetric training over Bass Strait. Making up the crew of 5 were flight engineer Warrant Officer Jon Fawcett and loadmaster Warrant Officer Al Gwynne. We cannot know what Lewin was thinking as the 707 completed its characteristically dramatic (compared to modern turbofans) take-off and tucked its gear into its belly, but it would seem reasonable to assume relief at being back in the sky and away from his overloaded desk for a few hours might have been among his thoughts.

Countdown to disaster

At 1147:38 Sale Approach ATC heard 2 incomplete mayday calls. A few seconds later the crews of fishing boats and several people along the coast near East Sale saw a large aircraft dive into the sea in a near vertical pitch attitude, spiralling to the left with objects separating from it. There was no possibility of surviving such an impact. Wreckage was found in 3 sections in relatively shallow water and recovery of the flight data and cockpit voice recorders (FDR and CVR) was relatively straightforward. What the recorders revealed shocked the RAAF to its core. While there had been 4 other crashes of Defence aircraft that year, killing 8 people, this was the first crash for the RAAF’s Transport Group since 1961.

Windsor 380 had made a three-engine touch-and-go landing at East Sale and headed south into Bass Strait to the East Sale training area. Here Lewin discussed flight at what he called Vmca, (Velocity minimum control, air). In using this term he was not quite correct, strictly speaking, because the Boeing 707 has 2 mca speeds: Vmca1 refers to minimum controllable speed (without an uncontrollable yaw developing) with one engine out. Vmca2 is the minimum control speed with 2 engines out, which is a much stronger imbalance of forces. Ellis concurred with the simplified definition – Vmca. The limits of their understanding would soon become horribly significant.

After a discussion of how the manoeuvre would be taught, Ellis, in the left seat, attempted it. His first step was to switch off rudder boost. Instead of being powered by hydraulics, the rudder would then move in response to a manually activated trim tab. Ellis took an optimistic view. On the CVR he said, ‘If we have any problems, rudder boost on will give us a whole bunch more rudder if we need it.’

Lewin set 25 degrees of flap and the CVR recorded the sound of the right engines increasing to what audio analysis measured as 81 per cent N1 rpm. Soon after, Ellis said, ‘Oh, I’ve got full rudder in’. Responding to Lewin’s direction, he selected the peak of Wilson’s Promontory as a reference point.

Fawcett, the flight engineer said, ‘Is that, ah, full rudder?’ and a few seconds later, perhaps indicating concern, he repeated, ‘Is that full rudder with boost off, is it?’

Ellis said, ‘That’s full rudder there with about 12 degrees’. Then Lewin said something that, with the luxury of hindsight, falls in the category of utterances that should never be heard on a training flight, ‘There you go, well that’s something I didn’t know before,’ about 12, 12 degrees.’ (He was talking about how the rudder travel was reduced by more than half, from 26 degrees, when boost was switched off.)

Windsor 380’s speed as he said this was 156 knots. The right engines were throttled up to 83 per cent N1 rpm and, as the aircraft slowed to 148 knots, Ellis added opposite aileron ‘to keep the wing up’.

Lewin remarked, ‘We’re right on min manoeuvre speed at the moment with flaps 25 so just be very careful’.

For about another minute they flew at 148 knots and gradually built the right engines to 95 per cent N1. The sound of airflow over the flight deck windscreen would have been joined by the distant grinding roar of low-bypass turbofans at high power. They were flying at just over landing speed, in a sideslip, at 5000 feet. Analysis found the pressure on the co-pilots right leg through the rudder pedal would have been in the region of 80 kg, equivalent to a hefty leg press in a gym, held for 3 minutes.

Ellis said, ‘I’m getting towards, but not quite at Vmca there. I’ve got almost full rudder in, and, you know, half aileron to maintain directional control’.

The pilots were discussing whether to slow more or add power when Lewin said, ‘There it goes now … starting to diverge now, yeah’.

The aircraft flew for about 20 seconds in this state, with N1 reduced to 60 per cent, before the CVR recorded a ‘grunting sound, like being winded’. It came from Ellis.

Lewin, still instructing, said, ‘Wrestle with the beastie!’

For about 30 seconds the aircraft yawed to the left at 6 degrees a second, in a slow skidding turn. Then, shortly after Lewin asked Ellis, ‘so how are we going to get out of it?’, Windsor 380 snap rolled into a steep nose down spin. The CVR recorded the rapid clacking of trim wheels, the sound of stick shakers indicating a stall, random impacts from objects flying round the flight deck and grunting from the 2 pilots.

At the point of departure from controlled flight, audio analysis measured the power being generated by each engine as: No. 1: 49 per cent N1 (idle power), No. 2: 60 per cent N1, Nos 3 and 4: 95 per cent N1.

The FDR registered a rotation of 60 degrees per second as the spin became fully developed after 7 seconds and continued through 2 revolutions until impact. Gravitational forces on the flight deck cycled between 1 g and 2.9 g. Under these conditions it took 17 seconds for the crew to reengage rudder boost. By then it was too late. The last words of the crew were delicately described in the CVR transcript as ‘exclamations’. They included a coarse and mournful appraisal that has haunted relatives who heard the recording: ‘****! You’ve killed us!’

Lewin, still instructing, said, ‘Wrestle with the beastie!’

Shock and breakdown

Mark Duncan and his 2 elder sisters had become close since the deaths of their parents in the late 1980s. Andrea Greenwood remembers how the domestic tedium of hanging nappies on the clothesline had been relieved by a thought about her brother, and his much less mundane life. At that very moment she heard her then husband ask, ‘Hey Andie, what sort of plane does Mark fly?’ When she answered with, ‘a 707, why?’, he told her, ’One’s just crashed’.

‘I just knew it was him – it was bizarre,’ she says. There followed an afternoon of confusion, uncertainty and shock, not just for the men’s families, but across the RAAF. Greenwood called the Richmond base and was told there was no information about any crash.

‘I was thinking maybe no news is good news,’ she remembers. But that afternoon she heard from her brother’s wife, Lisa, who, with Ellis’s wife Kay, had been on shift in the Richmond base control tower as ATCs at the time of the crash. ‘I asked her was everything all right and she said “No”. She couldn’t’ say any more, couldn’t get the words out.’

Stunned silence was a theme of Greenwood’s memories from that time. ‘I remember at the funeral, people couldn’t talk to me because they didn’t know what to say. The accident knocked the wind out of people in the RAAF, just disbelief that something like this could have happened.’

Analysis

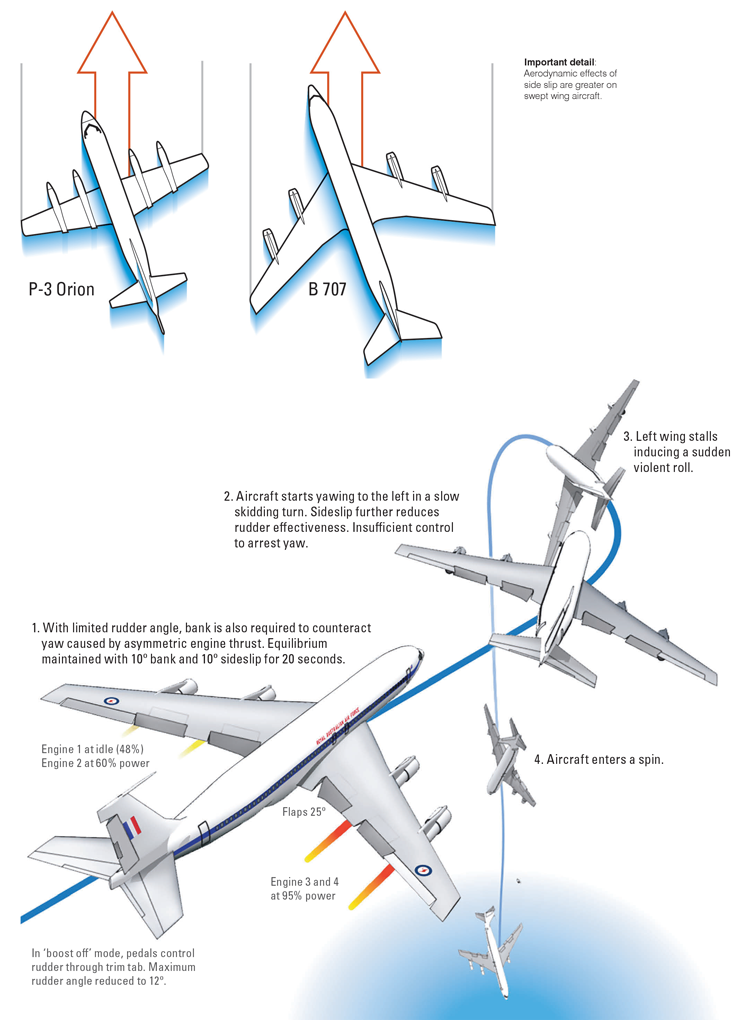

1. Aerodynamics of departure

A multi-engine aircraft with one or more engines not running on one side is kept in straight and level flight by a combination of rudder, bank and sideslip, all towards the operating engines. Theoretically, it could be kept straight and level by any of these any 2 of these 3 inputs. The RAAF’s accident report, published in 1994, discusses each approach. On the zero rudder condition, in which the aircraft is kept straight and level by a combination of bank and sideslip, the report says, ‘Although the zero rudder condition is on the limit of possibility, the speed required to achieve it might be so high – especially in the case of 2 engines out on one side – that it becomes strictly academic for all but aircraft with fuselage mounted engines’. With rudder boost switched off, Windsor 380 slouched towards the zero-rudder condition. The available rudder travel of 12 degrees was further reduced by the effects of sideslip.

The RAAF inquiry listed 5 triggers that might have caused a departure from controlled flight:

- Flight control malfunction – no evidence of this was found

- Engine malfunction – no evidence of this was found

- Adjustment of thrust – not recorded on the CVR

- Relaxation of pedal force – ‘It is therefore possible that as a result of fatigue the co-pilot involuntarily relaxed rudder pressure,’ the inquiry found.

- Reduction in bank angle – This would have overcome the compromised rudder authority.

2. The organisation and departure

Nothing and no-one suggested Squadron Leader Lewin was anything less than a dedicated, careful and skilled pilot. Many years after the crash, tributes on social media describe him as ‘one of the world’s great gentlemen and pilots’ and a ‘good bloke with the right stuff’.

His previous service was on the Lockheed P-3C Orion maritime patrol aircraft on which, as QFI, he demonstrated asymmetric flight many times. However, the P-3C differs from the Boeing 707 in one highly significant aspect – it has a straight wing, which is much more tolerant of asymmetric flight. As the report says, ‘Swept-wing transport aircraft are very sensitive to large sideslip angles and the dynamic conditions which are induced when sideslip is increasing at some rapid rate’.

The RAAF report described Lewin as ‘an excellent and responsible instructor and pilot’. Its search for contributing factors to the accident went beyond the flight deck and crew to examine 33 Squadron and, by implication, the RAAF. It found widespread and consistent organisational failings, including inadequate documentation for the type, which had been in RAAF service since 1979.

‘There was evidence to suggest that, when the B707 was introduced into RAAF service, inadequate research was conducted into the operating characteristics of the aircraft, including lesson learned by other B707 operators,’ the report says, adding that, ‘inadequate attention was given to documenting relevant operational information in RAAF-issued or authorised publication’.

The report goes on, ‘There were no approved publications … describing the procedure for demonstrating or practising Vmca or any other minimum speed thrust control exercise, or detailing any limitations applying to such demonstration or practice’.

A copy of a 1965 Boeing 707 flight manual was found at Lewin’s house. It prescribed 5 degrees of bank for Vmca1 and Vmca2 and listed 190 knots as the airspeed for a rudder boost off exercise. It is not known if the busy Squadron Leader found time to read this.

The report found 33 Squadron was still feeling the effect of the high turnover of instructors and executives and associated loss of experience and corporate knowledge that occurred

in the 1980s.

A bitter irony was that Vmca asymmetric training was not in the Boeing 707 conversion syllabus.

Lewin had been left largely to his own devices in 707 training, the report found. Information transfer had been informal and personal between Squadron QFIs, but this nexus had been broken when the previous QFI had been posted away before Lewin had finished his training. A bitter irony was that Vmca asymmetric training was not in the Boeing 707 conversion syllabus and the RAAF’s central flying school did not require it to be demonstrated. It had become a feature of 707 training, nevertheless. The report found Lewin had been shown a Vmca2 exercise in his conversion and had taught Vmca2 in the simulator and Vmca1 in the air.

The Directorate of Defence Aviation and Air Force Safety summarised the situation in a later publication, Sifting through the ‘90s. ‘In this accident, a well-intentioned highly motivated individual, in his relatively new squadron role as officer in charge of training, devised what he perceived to be a necessary training sequence. However, organisational stressors, coupled with the members incorrect transference of previous aircraft type experience without appreciating the differences to his current type, resulted in tragedy.’

Two salient lessons emerge from the destruction of Windsor 380 and apply equally to civil aviation as military. For the individual, the lesson is that a thorough understanding of aircraft type characteristics is the difference between life and death. For an organisation and its managers, the crash is a case study in the insidious and far-reaching effects of stress, which increases risk and error in organisations as surely as it does in individuals.

CAUTION:

With the rudder boost system inoperative, the capability to control the airplane under asymmetrical thrust conditions is greatly reduced.

From the Boeing 707 training manual

Legacy

Severe accidents affect many human lives, in addition to those who are killed or injured. For these secondary victims, the surface of everyday life takes immeasurably longer to return to calm than the surface of the sea did on that Tuesday morning.

Kay Ellis found the military’s processes for dealing with next of kin unsatisfactory – to use a neutral word – and did something about it. She appeared before a Senate inquiry in 1998 into military justice procedures, including the conduct of military boards and courts of inquiry. She wrote a guide to how deaths could be better handled: Australian Defence Force Commanders Guide: Looking After Families Following a Service Death was published in 2008.

Squadron Leader Kay Ellis died of cancer in 2011. Lisa Duncan died aged 49 in 2017 and Andrea Greenwood suffered autoimmune illness in her 30s. ‘You can’t draw any definite link, but we all endured stress grief and loss,’ she says.

Just over a year after the accident, Greenwood found herself pregnant again, despite having thought her family was complete. She had a son – and named him Mark.

A horrible day for the RAAF and I remember even though i was in the fighter squadrons at the time where we had had some bad accidents recently with the loss of Ross Fox and Cameron Conroy, we felt it was kind of expected with fighters – but a 707?

It did lead to a huge change in RAAF training culture, including the procurement of new B707 and C130H Flight Simulators and a greatly enhanced Airlift training system and the RAAF generally.

Lest we forget

WE are all armchair experts after a crash. There are three things to be alert to with large transport, swept wing jet aircraft.

1. Never side-slip if at all possible to avoid doing so – the break will be abrupt and likely unrecoverable.

2. Slow speed manouvre, even when wings are near level are high risk so avoid if possible.

3. Large jets lose altitude VERY rapidly given any excuse to do so. VERY rapidly is an understatement.

As a brand new 700 total hour Fokker F27 trainee, the VMCA exercise in type training with the incorrect engine for weight and speed selected, resulted in a snap invert. About 1500′ was required to recover carefully. I would add a zero for a swept wing jet IF it is recoverable at all – breakup would be likely.

The event had an additional couple of complications that has not been mentioned that are pertinent.

1. The B707 employed roll control augmented by differential spoilers. The left yaw that was encountered gave a roll moment to the left, and that was countermanded by right aileron, and right spoiler. The effect of the spoiler is to require an increase of CL from the remainder of the wing to retail level flight. That increases the stall speed further.

2. The -300 series aircraft had marginal dutch roll characteristics in the approach/landing configuration with the yaw damper inoperative. When the rudder boost was selected off, that removed the yaw damper. Paradoxically, the high yaw angle that ensued acts to reduce the resultant dutch roll.

The PIC’s prior experience on the P3C set a stage for a level of comfort with an abnormal operation which was sadly deep into the envelope where catastrophic outcomes could arise. The P3 was a remarkably benign handling aircraft, with graceful manners.

Any swept wing aircraft at low speed and with yaw on has a potential to encounter an elevated stall speed, and where supplemental roll control is incorporated, that is further increased.

The B707 departure was an accelerated stall more than it was a Vmca2 event, but the set up was from the yaw that had been set up.

Some time back, I was evaluating an instructor in a B738 sim, and the profile included an off axis microburst encounter. The sim departed controlled flight a number of times, and the hapless crew were sent off for coffee to commiserate. I conducted a QTG series and it was apparent that the sim was responding to the rapid yaw rate that was being developed by the microburst, resulting in the aircraft having an elevated stall speed and being out of balance in the sequence, and doing an impressive flick roll. The sim was quite faithful, and the crew were brought back in and briefed to be aware of an elevated stall condition; the PLI being great for balanced flight, not so much for out of balance… Where this stands today I have no idea, and I have done a fair number of stalls in B737’s clean, dirty, accelerated and high altitude. It is not a bad aircraft, but entering low speed with yaw on is best done in a Pitts.

Gold from Peter Ireland – thank you!

Hi I saw 103 out that morning doing a walk round with I think with one of the Warrant Offices Jon Fawcett or Al Gwynn I now that I remember the Australian coat of arms rank slide on his shoulder on his jacket or flying suit one of them was doing the fuel test under the the wings I pulled the stairs back about 1030 hours watch the aircraft fly out of sight on my RAAF yellow bike got a hell of a shock when LAC Shane Billtoff came and told me 103 has gone down I was in cargo hold of 624 I think when Shane told me . LAC Wally Walden B 707 486 Maintaince RAAF Richmond …..Lest We Forget Amen.