Keeping current in the fundamentals of navigation is vital, even in the digital era

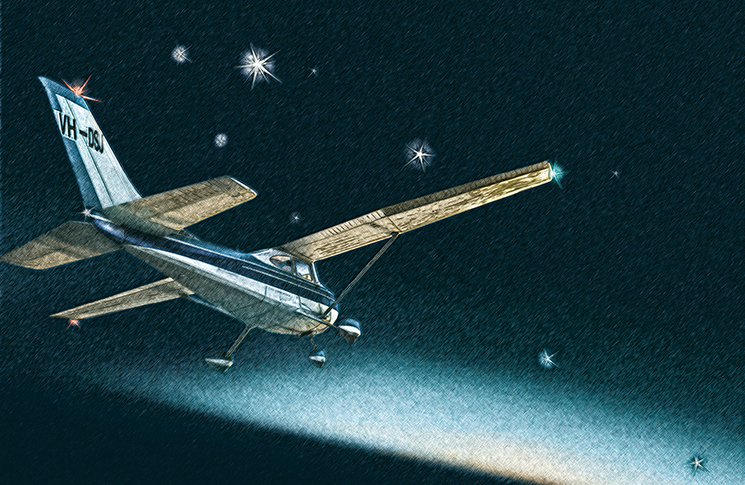

It’s been a stunning morning in the air. Two pilots, best mates, are out for an adventure a lot further afield than they’d usually fly. After a while, things start to get a little heated in the cockpit.

‘Whaddya mean you don’t know? It’s right there in front of you, Baz, on the screen. What’s the heading to Ern’s farm?’

‘Well, yeah but … ’

‘Geez, Baz, I give you one job! Keep us on track. What’s the iPad telling you?’

‘Well, not much, Wal. The screen went black a few miles back.’

‘Whaddya mean it went black? Make it come back on with our track on the map.’

‘Another thing, Wal – is it meant to be really hot like this? I think she’s buggered mate. Where are your paper maps? Did you bring any?’

Wal stares out the windscreen, feeling the colour drain from his face. The last time he used a paper map for navigating, he had a full head of hair and could still see his belt. He’d thrown an old WAC into the bottom of his nav bag this trip, in an optimistic attempt to be ‘legal’, idly wondering whether there’d been an update since 1997.

As his mind then drifted to a long-forgotten world of protractors, magnetic variations, position fixing and ETAs, Wal could feel the blood pressure rising …

Up for the challenge?

We all know how reassuring that unwavering magenta track is on our GPS or EFB screen. What a wonderful backup for our navigation! But what is backing it up? And what are we going to navigate by if all those bright shiny screens suddenly turn very black?

Reliance on technology can creep up on you, which is unsurprising if you use it all the time. So, this issue we thought we’d shout you a free visit back in time, back to the night before your first solo PPL nav, and the Genie from Hell has denied you any technology. That’s zilch. Zero.

My maps look like a happy dog’s breakfast by the time I get home.

I knew you’d love this game. How are you feeling about now? Do you trust yourself on tomorrow’s flight with just a paper map on your lap, a timepiece in view, taking position fixes and identifying landmarks? How about that 1-in-60 thing? Could you pluck that out of your memory bank to help you get back on track? Will you even recognise that you are off-track?

I know … nightmare, right? Here comes a little refresher.

The big ticket items

Student pilots doing nav training towards their PPL, or RPLs on the path to a nav endorsement, don’t get a choice. We are still teaching the time-honoured method, where these basic disciplines of dead reckoning have to be mastered without technology before that all-important handshake is offered at the end of a flight test.

You can’t talk about successful navigation unless you believe that thorough flight planning is key. Even if you don’t remember what a paper map is, you will remember the first stages of the planning process:

- draw tracks on the PCA, WAC, ERC (and VTC if applicable)

- note control zones/airspace/PRDs

- note radio frequencies

- measure distances and bearings

- did you remember about magnetic variation?

- select cruise levels, considering terrain, weather and direction of travel.

An understanding of the effects of cloud and wind on your entire route and, in particular, on your ability to maintain your planned flight path on any given leg, is paramount. While you have a GPS track in front of you, a large chunk of the need for decision-making, based on weather assessment, is taken away. You’ll just change your heading to get you back onto that magenta track whenever you drift off it.

As reliable as technology is these days, I just don’t fully trust that information on the screen not to vanish in front of my eyes. Whenever I’m away outback, say on a Kimberley trip, even though I’m using the insanely clever G1000 GPS in a glass cockpit C182, I’ll take all 24 WACs with me, marked up and will have one on my lap the whole way. That’s not being a goody two-shoes – I just feel a hell of a lot safer. And it’s fun! You can draw in uncharted airstrips you find, add homesteads, pubs, look for towers, whatever. My maps look like a happy dog’s breakfast by the time I get home.

Positive fix

Drawing lines on paper maps has a key benefit. It drags your attention to the terrain and landmarks over which you’re about to fly. You’ll notice things you can potentially look out for along each leg, to help you get your bearings.

So, let’s talk about position fixing. Along that track line you’ve just drawn on your map, you’ve also drawn prominent 10-mile markers. Remember them? That’s where you’re going to note your ETA (estimated time of arrival) on the left-hand side of each marker and an ATA (actual time of arrival) on the right-hand side. That last sentence has saved my bacon more times over the last 20 years than I can count.

If there’s no ground feature to suggest you’ve actually arrived at that marker, don’t stress. Just wait until you’ve positively identified a landmark further along your track. And when you do, use a unique symbol (I use a triangle) exactly over the spot and write the time down next to it.

Freeing up some headspace and relaxing a little while you’re flying is really important.

Comparing the time of this positive fix with your nearby estimate then either confirms or allows you to amend your ground speed and adjust your future ETAs accordingly. I generally have about 40–60 nm ahead marked up, so if I’ve forgotten to mark off an ATA, I can look at my watch, check my ETAs and think ‘OK, I should be about here somewhere’.

On the topic of those ETAs, they only work if you’ve got a handle on your ground speed, right? So what speed do you use in the climb-out? As you may have detected, I’m allergic to using my brain unnecessarily in the cockpit if it can be avoided. That particularly goes for those first 5 or 10 minutes after take-off, when the workload can be high. I want to be eyes outside, ears alert to local traffic and attempting to find something vaguely resembling my planned track.

Assuming nil wind, if our normal cruise speed is 120 knots indicated airspeed (KIAS), then 10 miles will take 5 minutes. But while we’re climbing, say, in the C172, we’re back at about 80–85 KIAS. I know you already have your whizz wheel out here … at that speed, 10 miles is going to take us more like 7–7 ½ mins. So, when we write our ETD on our map, we can now quickly add on 7 minutes and mark that time as the ETA at our first 10-mile marker. It’s not going to be exact, but it gives us a ballpark idea. We can use this method until top of climb and then use our planned cruise speed.

The big picture

When your navigation is going well, all the landmarks are popping up exactly when you are expecting them. But, if you miss a couple, don’t panic. It’s important not to sweat the small stuff. Chances are that little yellow dot on the WAC isn’t a sizeable town at all. I can’t tell you how many times we’ve said, ‘You call that a town?’ as we fly over a couple of old sheds and a handful of rusty utes.

Freeing up some headspace and relaxing a little while you’re flying is really important. If a particular landmark hasn’t turned up, it’s OK. Just confirm you’re holding the right heading, check the time, then lift your head and look out at the big picture. Are the mountains still out to the left where they should be? Is that huge river snaking slowly away from my track? Is the sun behind me as I’m tracking west this morning?

If you think you’re lost, the good news is that there’s very little chance you are!

Getting un-lost

If checking the big picture didn’t return any comforting reassurances, then it’s time to up the concentration.

If you think you’re lost, the good news is that there’s very little chance you are! First job is to make sure you have been flying the correct heading and that the DI is aligned to the compass. Then glance back to your latest positive fix. That positive fix combo of a triangle and a time is the most comforting thing you can have on your map. You know exactly where you were at that time and you know the time now.

In most light aircraft, we know we’re travelling about 2 miles a minute, so we can draw a point on the map where we ought to be. Unless you’ve randomly started flying your TAS or your wind direction instead of your heading, chances are you won’t be far outside a small arc around this point. Read from ground to map, and don’t get too hung up about minor roads not matching. They are notoriously unreliable once you get away from the cities; railway lines and rivers (even if they’re dry) are a far better bet.

Remember that climbing higher will give you a greater range of visibility and make use of railways and major roads to follow towards a town.

The One-in-60 rule

Sometimes you know exactly where you are, but it may be a mile or 2 off your planned track. You’ll hopefully have a think about why this may be. Maybe the westerly is stronger than forecast and has blown you off-track? Perhaps it’s because you’re flying lower than you planned due to cloud and the wind down here is blowing more from the north. Whatever the reason, to save getting yourself even more off-track, this is the time you could benefit from using the One-in-60 rule.

If you’re anything like me or a million other pilots, you know with certainty that the Devil created this rule, with the intention of making you feel as useless and confused as humanly possible. It’s reassuring to know that after a couple of decades of flying, I’ve got the hang of it now. If the One-in-60 has always done your head in, and you’ve never really felt confident enough to use it during flight, you’re not alone.

If you want to see an excellent explanation of how it works, just visit flight-club.com.au, go to videos and select their One-in-60 video. It is presented so well. I’m not going to try and beat that. Have a look and then practise with other examples at home.

So, how about that challenge of using no technology on your next flight? You’ll feel a bit rusty but I’m betting you’ll be totally fine. In fact, with some well-placed encouragement from Baz, Wal ended up dragging that paper map out and got them to Ern’s farm in time for a cold beer before the sun went down. He’s even thinking about updating his WACs.

Good article. One point is that you MUST have a back up for the ipad, even a phone with MAPs . One issue with the ipad is if you are in glare, eg day in cloud, and with turbulence your shaky finger fully dims the screen, it is impossible to locate the ‘undim’ slider bar.

1:60 rule is real nightmare, European-culture people can not operate in this system, it is worse than octets (3 bit numbers) in ancient computers. Thats the reason why all armies all over the world use simple and straight mils (1:1000 aka mrad) and no boiling brains occured even with young dummy conscripts.

And in general – backup is backup. It does not provide the same precison, effectivenes and convenience, but just allows not to fail completely. So paper map can not be relied upon to find a point in the middle of nowhere if gps fails, it can do this only if used as main tool, with all efforts and attention required and wasted 999 out of 1000 times. No one will do this ever and all of us clearly know this. Paper map can only be a safety net, an aid to return to safe point, find big city airport etc, together with proper route planning and knowledge “ocean is there”, “Sydney is behind the mountains” etc.

But in modern world even this is not relevant as gpses are everywhere now from watches and handheld radios to smart phones (with full maps, not aviation oriented but more than enough to find the point) and general use laptops. Be prepared, do not rely on the single device – and it pays back!

Fly IFR, nothing beats the I ‘follow roads rule’ most of the time :-). Big road signs are your friend!

Whoops, missed the turn to Longreach. :-)

Great article – not seen flight club website before, what a great resource!

One of those who learnt before EFBs so still enjoy the map reading side of it

Perhaps I’m a Luddite, but I really enjoy the paper map navigation aspect of flying. I only use the GPS as a backup, and frankly I rarely look at it.

Great article Shelley! I’m off to look at the 1:60 video.