The pilot had a frightening nickname, and a reputation as a confident, highly skilled rogue. But nothing was done until it was too late.

Aerospatiale AS350BA, Grand Canyon, Arizona, US September 20, 2003

The passengers waited excitedly for their once-in-a-lifetime Grand Canyon tourist experience – a short helicopter scenic flight down into the Grand Canyon. There they would board a boat and cruise along the Colorado River, before flying back to the top of the canyon rim and returning to Las Vegas on a fixed-wing aircraft.

This wasn’t a cheap day out and for many a rare experience to fly in a helicopter. The passenger briefing was completed and they all climbed onboard. The company loader knew they were in for an exciting ride as the pilot was nicknamed ‘kamikaze’. There were reports of hearing passengers screaming with fear in the background over the radio as the pilot transmitted a position report while nosing the helicopter over into the Canyon.

The pilot hover taxied over the lip of Descent Canyon, a narrow side canyon that led down to the main Grand Canyon and landing area beside the river. The passengers marvelled at how they magically hovered over the desert floor unaware of what the future may hold.

Another pilot flying a helicopter on approach to the landing area beside the Colorado River looked up and noticed a large plume of dark smoke rising from within Descent Canyon – kamikaze and his 6 passengers were dead.

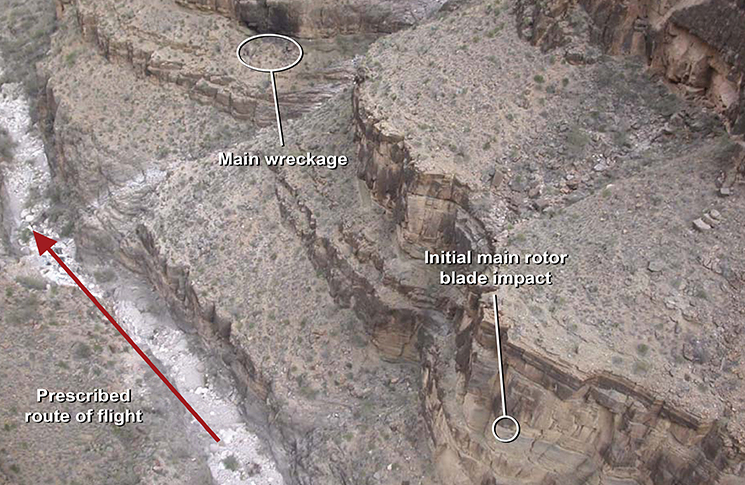

The Squirrel helicopter had hit a ledge on the side of the vertical canyon wall and caught fire. About 400 feet away, on a vertical section of the canyon, there was gouging consistent with a main rotor blade strike.

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) accident report concluded the probable cause of the accident was ‘the pilot’s disregard of safe flying procedures and misjudgement of the helicopter’s proximity to terrain, which resulted in an in-flight collision with a canyon wall’. Further contributing to the accident was the failure of the helicopter company and the Federal Aviation Administration to provide adequate surveillance of air tour operations in Descent Canyon.

Going wild in the canyon

Studies of photos and video images from passengers on this flight and previous flights undertaken by the accident pilot showed that airspeeds of 145–150 knots, along with a 55-degree pitch down and 99-degree angle of bank, had occurred during these sorties.

Grand Canyon tourist operators had imposed a series of guidelines called the tour operators program of safety. It is a voluntary program that puts safety as its number one priority and its mission to make helicopter sightseeing tours among the safest type of flying.

Operators who are approved by the program have committed to a higher standard of safety and to self-policing these standards. The guidelines required flights to be conducted with bank angles of no more than 30 degrees, pitch angles of no more than 10 degrees, along with smooth flight transitions and a maximum speed of 120 knots. The company that ran the sightseeing tours had signed up to the guidelines.

The company loader knew they were in for an exciting ride as the pilot was nicknamed ‘kamikaze’.

The pilot was experienced, with about 7,800 hours flying time, of which 6,700 hours were in helicopters, including 2,300 hours with the company when the accident occurred. He was a helicopter flying instructor and had previously owned and operated his own flight training school.

The pilot had earned a reputation for flying aggressively and hard though Descent Canyon. A former company pilot said the accident pilot was ‘an extremely good pilot, above average, he was more qualified in the helicopter than the job demanded, he was a phenomenal man to work with’. He said the accident pilot ‘worked the helicopter, pushed the aircraft and pushed the rules of flight in Descent Canyon’.

Other company ground staff also knew the pilot flew the aircraft hard, because they were ferried down to the Colorado River landing site each morning on the same route. ‘Hundreds of people flew with him and knew the way he flew … he scared people down the canyon – if one little thing goes wrong, we are, you know, dead’. In short, this pilot was going rogue!

In one case, a passenger formally complained in writing about ‘a very dangerous pilot in charge of the helicopter – I thought I was about to die. He flew so fast and dangerous. I could not believe his behaviour’.

A further complaint 2 months later from the CEO of the fixed-wing company providing the trip to and from Las Vegas stated, ‘[The CEO] was asked if he wanted a helicopter ride or an ‘E’ ticket ride’.

He received a ride that included abrupt banks and did not meet the standards of the guidelines. An ‘E’ ticket is a former Disney term that classifies its theme park rides as thrilling.

The helicopter company decided to suspend the pilot for one week and gave formal notification. However, because this was to occur in the company’s busiest time, the suspension was delayed and then forgotten.

Pay for a thrill

There was evidence several of the company pilots were exceeding the flight times allowable under the guidelines.

Seeking tips was not company policy, however, this was not written down. There was evidence tips were sought – a photo recovered from the accident showed a small removable sign mounted on the centre canopy stating, ‘Gratuities are always appreciated – thank you’.

Seeking tips might encourage pilots to provide a thrilling ride that, over time, could exceed the guidelines and become reckless. The company had previously sacked a pilot for going nearly vertically down into Descent Canyon.

A least one pilot, who had flown in Vietnam, refused to fly the Descent Canyon trip because he considered it unsafe.

A Reasoned analysis

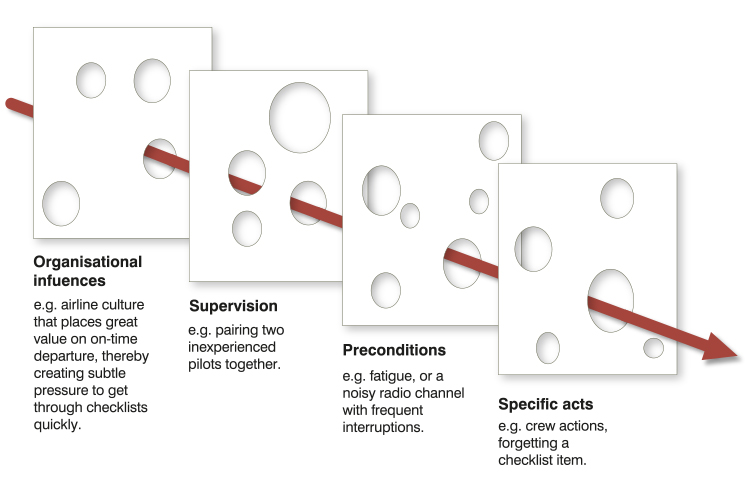

Let us use the Reason model to help analyse this accident. Obviously, the active failure was the unsafe act of flying too close to the canyon wall, which the rotor blade hit.

In the latent failure area, we can see the precondition for unsafe acts was the developing, aggressive flying style of the pilot where he exceeded the flying guidelines. Further preconditions could be the taking of tips, boredom from flying the same profile repeatedly or the inability to actually fly the Descent Canyon route within the guidelines.

Unsafe supervision was evident in the minimal understanding of the chief pilot about what was happening in the day-to-day operation of the flights. If the chief pilot knew what was occurring, then the lack of action to reign it in still amounts to unsafe supervision.

Organisational influences were the company failing to act over a long period of time, including the lack of enforcement of the suspension, not following up on the evidence from the pilot who refused to fly the profile because he considered it unsafe, as well as complaints by several passengers. These are all holes in the accident causal chain that lined up.

Therefore, as a manager of an aviation company, what organisational structures might you set up to maintain safe operations? As a flight supervisor, what might you do to provide oversight of your pilots? Regular check rides may not be sufficient as pilots can fly one way on checks and another when no-one is watching.

Remorse and reform

After this accident, the company implemented post-flight surveys for all passengers to identify safety issues and immediately followed them up. They also implemented a ‘ride-along’ policy where non-company pilots were offered free anonymous trips to observe how the sorties were flown.

There are also several systems that record in-flight video, aircraft attitude and speed, that could be fitted to the helicopter. Randomly downloading these to assess how the aircraft is being flown would provide some level of supervision or surveillance.

Tourist flights are not the only operations where the desire to keep pushing the limits can occur. Two comments may indicate some of the driving factors. One company pilot said, ‘From time to time, I got bored on the tour and tried to give the passengers an additional thrill’. Another said the accident pilot was ‘more qualified in the helicopter than the job demanded’.

From time to time, I got bored on the tour and tried to give the passengers an additional thrill.

Repetitive, boring flying that does not challenge people can lead to unsafe outcomes. The motivation may not be to show off – it may be an experienced pilot trying to become more efficient or challenge themselves. This could arise in any repetitive flying activity, such as marine pilot transfer, oil rig transfer, agricultural, fire fighting or survey.

It takes discipline to maintain the same standard, day after day. The often small incremental changes that lead to an eventual large deviation from the safety norm is called practical drift. The small steps away from the safety baseline go unnoticed and seem inconsequential at each small increment. However, over a long time, these small steps add up to create large gaps.

If you made the jump from the safety baseline to the end state where you had drifted to in one go, it would be obvious, noticed and uncomfortable. However, by taking small steps that are repeated many times without immediate consequence, you become desensitised to the eventual drastic change. This incremental change can fundamentally undermine safety and lead to catastrophe.

There were attempts by management and fellow pilots to reign in kamikaze’s behaviour. However, a pilot who is very good at piloting the aircraft and has many flying hours and a lot of experience can be difficult to confront.

Further, an experienced and bored pilot needs to have a level of insight to prevent themself becoming a rogue aviator. Tony Kern studied a B-52 bomber accident at an airshow where leadership failed to control a rogue pilot. The article, Darker Shades of Blue: A case study of Failed Leadership led to him writing several books including Redefining Airmanship and Flight Discipline. This series of writings sets up a framework for establishing and maintaining airmanship and flight discipline at personal and organisational levels.

Incremental change can fundamentally undermine safety and lead to catastrophe.

Most people rarely fly on helicopters. Those who can afford a tourist flight are normally amazed at the magic carpet ride. The guidelines’ limits of 30 degrees angle of bank, pitch angles of no more than 10 degrees, smooth flight transitions and a maximum speed of 120 knots, will provide ample value for money. Going any further than this is just satisfying the pilot’s ego to show off.

Tragically, in this case a lack of discipline and airmanship by a rogue pilot combined with poor supervision meant what should have been a safe enjoyable day out turned into a tragedy.

This says it all, “A least one pilot, who had flown in Vietnam, refused to fly the Descent Canyon trip because he considered it unsafe.” And, “the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) accident report concluded the probable cause of the accident was ‘the pilot’s disregard of safe flying procedures and misjudgement of the helicopter’s proximity to terrain, which resulted in an in-flight collision with a canyon wall’. ”

Further, “Repetitive, boring flying that does not challenge people can lead to unsafe outcomes. The motivation . . . may be an experienced pilot trying to become more efficient or challenge themselves.”

Well, if ‘kamikaze’ (the nick name for the rogue pilot, wanted to become more efficient and challenge himself, there are much better ways to do it. Go out to earn an advanced Rating for get checked out in a different Type, earn an Instrument Rating, if he didn’t have one, if only a Commercial Pilot, then he could have earned an ATPL . . . But, he should not have been horsing around with passengers on board.

I recall, back in 1992 to 1994, I was feeling pretty stale and wanted a challenge, so I went out to earn a Commercial Seaplane Pilot Licence, getting checked out flying a single engine Seaplane, then got checked out flying a multiengine Seaplane.

A truly professional and conscientious pilot will find ways to challenge what he/she thinks he/she knows about Aviation, by learning more and maintaining self-discipline, cockpit discipline, and proactively employing Crew Resource Management and Threat Error Management strategies, in his/her flying. A truly professional and conscientious pilot will know his/her personal limitations and, like aircraft Limitations, never exceed them.

Over-confidence and blatant disregard for the rules and regulations will ultimately have only one outcome.