W.H.Auden, Musée des Beaux Arts, 1939

Other than the incantations of ATC and the litany of checklists, they left the earth without ceremony. There were no children with faces pressed against passenger windows for this was a cargo flight, about as memorable as the movement of a truck. The thoughts of the 2 pilots were most likely concerned with departure procedures and perhaps anticipation of 55 hours off duty in Cologne, Germany, their destination.

Among the issues that Captain Doug Lampe, 48, and First Officer Matthew Bell, 38, had dealt with in the previous flight from Hong Kong was a troublesome flight deck air-conditioning pack. When reset, this unit – A/C pack 1 – had appeared to work perfectly, but it tripped off again as the Boeing climbed through 10,000 feet. Another reset seemed to fix it.

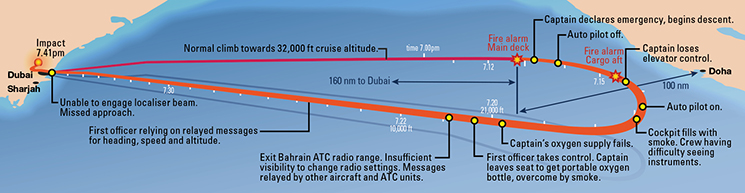

Suddenly, on the departure from Dubai, routine shattered. The master fire warning sounded its deliberately disturbing alarm clock ringing rattle, and FIRE MN DK FWD lit on the annunciator panel. Without hesitation Lampe said, ‘Fire, main deck forward. Alright. I’ll fly the aircraft’. Two seconds after Bell’s acknowledgement, Lampe said, ‘We’re gonna return.’

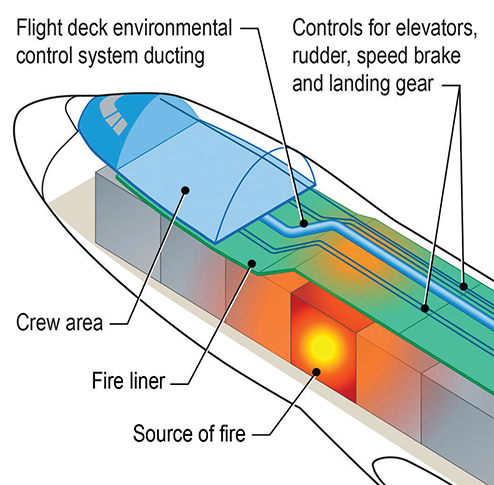

Bell opened the non-normal checklist and called its first item – ‘Don the oxygen masks’. The fourth item on the eight-point list was to arm the cargo fire switch and the fifth was to shut down A/C packs 2 and 3. This was to isolate the cargo deck and have A/C pack 1 provide positive air pressure to the flight deck to keep smoke away. Soon after, but unnoticed in the workload, A/C pack 1 failed again. There was now nothing to prevent smoke invading the flight deck.

Meanwhile, Lampe was holding a terse conversation with Bahrain ATC. ‘Just got a fire indication on the main deck, I need to land ASAP.’

‘Doha at your 10 o’clock at 100 miles, is that close enough?’ the Bahrain controller replied.

Lampe said, ‘How about we turn around and go back to Dubai, I’d like to declare an emergency. ‘

During the turn, Lampe switched from autopilot to manual control and requested clearance down to 10,000 feet. He immediately found difficulty controlling the aircraft through the yoke and mentioned this to Bell, who was having difficulty hearing him through his mask and was probably having difficulty seeing him. ‘Penetration by smoke and fumes into the cockpit area occurred early into the emergency,’ the accident report published 3 years later says.

Four minutes and 21 seconds after the first ring of the fire alarm, Lampe transmitted: ‘UPS 6 we are full … the cockpit is full of smoke, attempting to turn to flight to 130, please have … standing by in Dubai.’

At Lampe’s suggestion, Bell opened the flight deck smoke vent, which had little effect. Staining found on fuselage fragments attested to the thickness of the smoke.

Lampe said, ‘Try and get Dubai in the flight management computer (FMC)’

Bell replied, ‘I can’t see it (FMC).’

Two minutes later, the cockpit voice recorder had this exchange:

Lampe: I got no oxygen, I can’t breathe.

Lampe: Get me oxygen.

Bell: I don’t know where to get it.

Lampe: You fly.

The report says, ‘Conversation and ambient sounds indicate the captain moved the seat back, got out of the seat and then moved to the aft of the cockpit area.’

Toxicological analysis found fatal levels of carbon monoxide in Lampe’s remains. He lost consciousness in his attempt to get the spare oxygen mask near the jump seat and died soon after.

There was now nothing to prevent smoke invading the flight deck.

Blind hell

It’s hard to imagine a more horrible situation than Bell’s predicament: isolated and unable to see the instrument panel or tune the radios. For these reasons and the flight control issue, which was due to fire burning through the cargo deck fire resistant liner, roasting and slackening the control cables, he was only nominally the pilot.

Lampe had discovered that the aircraft was still controllable using the autopilot, which bypasses the 747’s control cable system. This is why he asked Bell to ‘get Dubai’ in the FMC.

Despite Lampe’s disappearance, and probably not being able to see the FMC panel, Bell managed this. The aircraft stabilised at 350 knots, descending on a heading of 105 degrees to intercept the localiser for Dubai runway 12.

A new problem arose in the descent. Bell was unable to switch the radio to Dubai and decreasing altitude meant he lost line-of-sight transmission to Bahrain. Another radio on the flight deck was tuned to 121.5 and UAE Area Control attempted to contact him on this international emergency frequency; however, the volume was turned down and Bell either forgot under stress or was unable to adjust the radio, even though he called mayday on this channel.

Other aircraft relayed his increasingly desperate messages to Dubai, but this required 3 steps for a single message and 6 steps for a reply. His frustration and anguish are evident in the official transcript. ‘Negative, negative, negative’ was Bell’s reply to ATC’s relayed suggestion to ‘make a 360’ after the aircraft flew too fast and high to intercept the glideslope.

By this time Bell would probably have been literally unable to see his hand held in front of him and was also being slowly poisoned. His oxygen mask was set to ‘mix’ rather than 100% oxygen – there was no checklist item for this.

After overflying runway 12 at Dubai, ATC cleared the flight to Sharjah Airport, 10 nm to the north-east. Bell attempted to enter 095 in the FMC but, blinded, entered 195.

He disengaged the autopilot and advanced the throttles, probably attempting to expedite the turn. He made several pitch-up inputs on the yoke, which briefly paused but could not arrest an implacable descent.

Although he had no way of knowing what lay below, Bell’s actions meant the aircraft avoided crashing into a residential and technology area, Dubai Silicon Oasis, where it might have killed hundreds. It crashed about 1 km west of the suburb, bringing the 27 minutes and 45 seconds of fear and suffering to a brutal end.

Bottled lightning

The investigation found fire had broken out in pallets of cargo on the main deck that included a significant number of lithium batteries and other combustible materials.

The thing that makes lithium batteries a hazard is the same characteristic that makes them useful: they store a lot of energy in a small volume. An early analysis summed them up as ‘bottled lightning’. In a world trying to transition from fossil fuels, this places them in demand.

The fire had escalated rapidly, despite the depressurisation of the cargo hold which reduced available oxygen. This was probably due to a distinctive characteristic of lithium battery fires: they generate their own oxygen. This happens when lithium-ion batteries are overcharged or damaged by an impact and go into thermal runaway. Then the damaged battery cell generates heat faster than it can be dissipated and fuels itself through chemical breakdown. Temperatures can reach 1,100° C, higher than the melting point of aluminium.

The thing that makes lithium batteries a hazard is the same characteristic that makes them useful.

Response

Partly as a result of the investigation of UPS flight 6, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) adopted a ban on the shipment of lithium metal (single use) batteries as cargo aboard passenger aircraft. The prohibition came into effect on 1 January 2015.

The crash also led to an innovation that is now on more than 8,000 aircraft flight decks. The emergency vision assurance system or inflatable vision unit is a gas pressurised inflatable transparent bag, designed to touch the aircraft’s flight display. A pilot wearing a smoke mask placing their face at the other end of the bag can see the instrument display. The device was patented in 1994 but not widely adopted until after the UPS 6 crash. Its maker, Visionsafe, says 69% of Part 121 cargo aircraft have been equipped with the system. Two deployments in emergencies have been reported to the manufacturer.

Fire containment pouches for portable electronic devices, with matching fire-resistant gloves, are available, at an expense proportional to their materials and engineering. Despite their eye-watering price, they would seem like the bargain of a lifetime if ever they had to be used in earnest.

The most effective way to deal with this hazard is to make sure it doesn’t happen.

CASA Dangerous Goods Team Leader Sam Bitossi is Australia’s nominee to the ICAO Dangerous Goods Panel. ‘The ICAO DGP has a standing job card solely dedicated to managing the safety risks posed by the carriage of lithium batteries by air,’ she says. ‘Measures and controls have been developed over the years, which have been adopted in international standards – the ICAO Technical Instructions for the Safe Transport of Dangerous Goods by Air – which is enacted directly into Australia’s legislation.’

Bitossi says Australia has specific legislation requiring safety information about the carriage of lithium batteries be provided to passengers and shippers of dangerous goods. ‘This demonstrates the importance of appropriate disclosure and carriage of such goods. Safety really is everybody’s responsibility.’

Countermeasures

Like every story of an in-flight fire, the story of UPS flight 6 makes the point that the most effective way to deal with this hazard is to make sure it doesn’t happen. For lithium batteries, this means taking a multi-faceted approach including addressing the risks of manufacturing, packaging, operational and public awareness.

For pilots confronted by an in-flight emergency, the first minutes of the UPS 6 story are worth respectful reflection. Lampe decided quickly to return to Dubai, despite Doha being closer, as the controller helpfully suggested. This probably made little difference to the outcome.

But it’s an established principle of 21st century crew resource management that metaphorically stepping back, taking a few deep breaths and casting your mind over the problem, helps good decision-making. Dutch carrier KLM uses the ‘reset, observe, confirm’ methodology, developed by Joern van Rooij and Edzard Boland, in training its pilots to cope with startle and surprise. It’s a sound practice even if in this case it may only have changed the location of the crash.

In the poem that accompanies this story, the ship whose crew saw Icarus falling from the sky ‘had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.’ This is precisely what we must not do.

Everyone involved in aviation, indeed anyone who uses modern technology, has a role to play in lithium battery safety. Never putting spare batteries in checked luggage, retiring battered electronic devices, using reputable repairers and ordering genuine rather than shoddily made low-cost replacement batteries, are small but collectively important actions that can mitigate the inherent risks that lithium batteries present in the sky.

New dangerous goods initiative lifts off

Industry partners, airports and airlines are invited to help travellers understand what they can and can’t pack as lithium batteries, power banks, vapes and other dangerous goods proliferate.

The communications push, under the new tagline ‘pack right, safe flight’, aims to reduce in-flight safety risks and prevent disruption. It offers simple and engaging advice, with ready-to-use materials such as new signage for passengers, airlines and airports.

There’s also a modernised dangerous goods search tool on the CASA website where travellers can check packing rules for specific items.

In addition, there’s a video, and news stories about the harmful impact dangerous goods can have and a way to report dangerous goods incidents.

Research shows that many travellers don’t know what items are considered dangerous goods. They want clear, early guidance – ideally from their airline and airport – at least a week before check-in.

The initiative aims to improve safety and reduce airport delays through clear and consistent advice aimed at reducing incidents from undeclared or incorrectly packed dangerous goods.

Visit Pack Right. Safe Flight. for further information.