Weather forecasts for aerodromes without an aerodrome forecast (TAF) are often broad and may not reflect local conditions. Graphical Area Forecasts (GAFs) are a great starting point. But when you need more detail, help is just a phone call away.

The forecaster on the other end of the line

Meghan Ridnell is an aviation meteorologist with the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM). She has worked at the Melbourne Aviation Forecasting Centre for nearly 4 years. Meghan issues many of the forecasts pilots use, including TAFs, GAFs and SIGMETs. SIGMETs warn of hazards such as thunderstorms, turbulence or mountain waves.

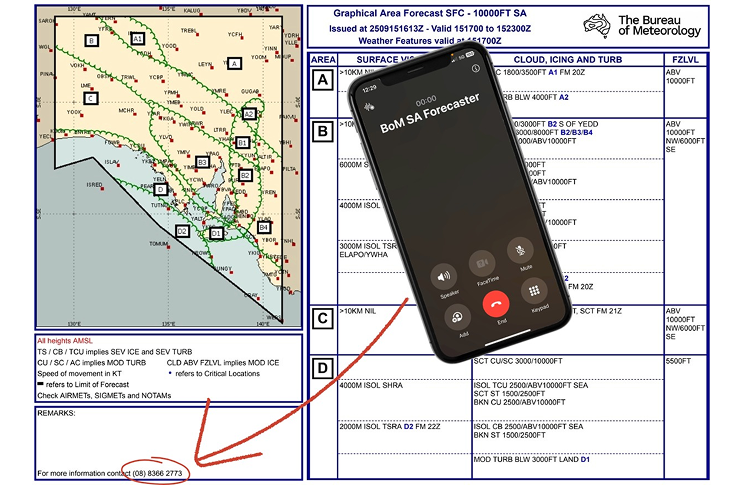

Each GAF shows a phone number in the bottom left corner. Pilots can call it to speak directly to the forecaster, often Meghan herself.

‘It can vary day to day and is very dependent on the amount of weather going on’ Meghan says. ‘We can receive up 20 calls on a busy day.’

‘Most calls are usually about giving more detail or clarity on the GAFs. Pilots ask about cloud bases, the extent of cloud or fog, where storms or showers are most likely and when.’

Meghan explains the extra tools she uses to help pilots. ‘We can visualise weather data spatially and in three-dimensions,’ she says. ‘We also have full access to satellite imagery and radar so can provide pilots with more information than what is given on the GAFs.

‘This includes more precise timing of weather features such as fog, storms and wind changes, as well as inversion heights and winds at different levels.’

Forecasters also have extra local knowledge to share with pilots flying in places without a TAF. ‘A large part of becoming a forecaster is learning the geography of where we need to forecast in detail. That means we generally have a good idea on what’s going on at most locations.’

How terrain, coastlines and valleys shape local weather

Pilots often talk with Meghan about fog, especially in south-eastern Australia. She lists the risk factors for fog. ‘Clear skies, light winds and a moisture source, such as recent rainfall or onshore flow, under high pressure are generally the biggest factors.’ This mix is common in winter.

‘However, local conditions can have a big effect. This makes fog one of the hardest things to forecast.’ Meghan’s comment highlights why pilots often ask for more information.

‘Topography plays a big part, creating more favourable locations for fog to form,’ she says. ‘These can include valleys, where cold air can pool and wind speeds are lower, or where the flow is blocked by hills or a mountain range allowing moisture to build up until fog forms.’

Conditions can vary even a couple of hundred metres apart. ‘It is not that uncommon for fog to be present at one end of a runway while the other end has clear skies,’ Meghan says.

It’s not just fog that pilots ask about. Summer brings a different challenge. ‘Thunderstorms are one of the phenomena we receive the most calls about.’

Managing thunderstorms en route is a challenge.

‘Local geography can play a part in where storms form or where they may collapse,’ Meghan says. ‘Factors such as sea breeze locations and speed of movement, or the local topography, can greatly affect where thunderstorms occur.’

Tools like BoM’s satellite viewer and its network of weather radars give pilots more detail. These tools show many of the images forecasters use. They also replay how storm cells, fronts or squall lines grow and move.

Planning and support for local weather

Pilots call Meghan about more than the GAF. ‘Other common questions are if a PROB30 [30% probability] or holding [INTER or TEMPO periods] for low cloud, fog or storms are going to be extended or upgraded’ she says. These items are associated with TAFs for a specific aerodrome.

It’s common for forecasters to get more details from these calls. Pilots’ local reports help them update forecasts. ‘Pilot weather reports, such as PiREPS or phone calls, provide valuable additional information for forecasters. While we have a great range of observations, including weather stations, radar and satellites, pilot reports can add context.’

Asking for help is simple but often overlooked when making a difficult decision. A long GAF or TAF often means the weather will be complex. But that alone should not decide if you stay or go. Even if you just want to check your understanding of the forecast, a friendly forecaster is only a phone call away.

Resources for weather and forecasting

Weather and forecasting resources are a focus of CASA’s Your safety is in your hands campaign. For more guidance, tools and tips, be sure to visit the pilot safety hub.

Comments are closed.